目前尚无单一的检测方法评估儿童营养状 态 [1] 。评估儿童营养状况需从病史中寻找高危因素、 确定临床表现,以相应的实验室方法综合评价营养 素代谢的生理生化状况。因此,评价儿童营养状况 包括“A”(人体测量,anthropometric measurement), “B”(实验室或生化检查,biochemical or laboratorytests),“C”(临床表现,clinical indicators),“D”(膳 食分析,dietary assessment) [1, 2, 3, 4] ,或概括为“ABCD” [3] 。 同时,评价儿童营养方法或目的因群体儿童和个体 儿童有所不同 [5, 6, 7] 。

儿童体格发育状况可间接反映儿童营养状况, 如反映身体成分(瘦组织、脂肪)变化。体重反 映能量贮存在脂肪组织增加或减少状况,身长的增长(或线性生长)直接反映机体非脂肪组织 (fat-free-mass)的增长。良好的营养条件下的儿 童线性生长代表非脂肪组织的生长潜能水平,即 身长(线性生长)反映生长潜力 [8] 。因此群体儿童 与个体儿童营养状况评估时常常采用体重、身(长) 高以及体重/身(长)高等体格发育指标 [9] 。

当有明确的临床症状支持诊断时需采用疑诊 营养素异常的相应的实验室检查方法,以帮助确 定临床诊断;同时实验室检查结果还可监测和评 估营养干预的反应。机体营养状况的信息可从检 测血浆、血清、尿液、大便等样本中获得,头发、 指甲的检测已很少用于临床 [1] 。实验方法的选择需 根据医学知识、病史、体格检查发现的相关问题。

营养素缺乏依儿童病理生理的改变分为Ⅰ 类营养素(功能性、预防性营养素,functional or protective nutrients)和Ⅱ类营养素(生长营养素, growth nutrients) [10, 11] 缺乏。因此,不同类型营养 素缺乏的临床表现不同,如Ⅰ类营养素缺乏时儿 童生长正常,营养素的组织浓度下降,有相应的 营养素缺乏的特殊临床症状;而Ⅱ类营养素缺乏 时则营养素的组织浓度正常,儿童除生长显著下 降外无特殊临床表现。此外,营养不良时有些营 养素缺乏可有相似的临床症状、体征,如贫血可 见于铁缺乏、锌缺乏、叶酸缺乏,舌炎可见于铁 缺乏、叶酸缺乏,免疫反应减退可见于铁缺乏、 锌缺乏、维生素A缺乏。因此,需要熟悉常见的 营养素缺乏临床症状、体征,结合膳食分析、实 验室检查资料综合分析。

长久以来我国儿科临床或教科书均将儿童营 养不良和超重/肥胖分别作为独立的疾病诊治,儿 童营养不良亦为蛋白质-能量营养不良(protein- energy malnutrition)的代名词。美国学者则称营养 缺乏为营养失衡 [13] 。发展中国家蛋白质-能量营 养不良的发生率较高,发达国家则表现为过多的 不健康食物摄入,如脂肪和精制碳水化合物 [14] , 导致超重/肥胖儿童增加。蛋白质-能量营养不 良和超重/肥胖的儿童不能维持正常组织、器官的 生理功能 [5] 。因此,近年来认为儿童营养不良不是 单一疾病,而是一种异常的状态,包括营养低下 (undernutrition)和营养过度(overnutrition) [5, 13, 14, 15] 。 营养低下是营养素不足的结果,而营养过度是摄入 营养素失衡(imbalance)或过量的结果。但多数国 家学者描述儿童营养不良时仍是食物不足或食物质 量差发生儿童能量-蛋白质营养低下的表现 [16] 。

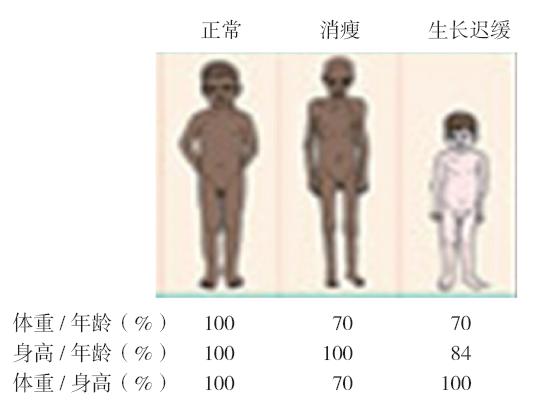

按体格发育指标判断儿童营养不良有低体 重、生长迟缓和消瘦三种情况 [9, 17, 18] 。三者可不一 致,只要有其中一项则提示儿童存在营养不良状 况,但不能确定病因。低体重的定义是体重低于 参照人群的体重中位数减去2 SD或Z值<-2,生 长迟缓则是身长(高)低于参照人群的身高中位 数减去2 SD或Z值<-2,消瘦是体重/身高低于 参照人群的身高中位数减去2 SD或Z值<-2。儿 童营养不良状况的严重程度则以中位数减去nSD 表示:“中度”为≤-2 SD~-3 SD,“重度”为 <-3 SD [9, 19] 。低体重儿童多同时存在生长迟缓,即 体重/身长(高)可能近于正常范围,无消瘦,即 相对身长而言低体重的儿童可有生长迟缓或正常, 甚至消瘦几种情况 [20] (图 1)。 目前,发展中国家 5岁以下儿童营养不良的主要问题仍是生长迟缓。 因此,近年WHO建议改进营养评估和营养不良分 类方法,以体重/身高判断儿童营养不良状况和评 估干预情况 [10] 。消瘦为儿童因各种因素致短期内 Ⅱ类营养素(生长营养素)中能量不足发生体重明显丢失,身长(高)尚未改变 [10] ,为“急性营 养不良状态”。过去称生长迟缓为“慢性营养不良”。 但儿童生长迟缓是一动态、累积、进行的状态, 生长迟缓(stunting)需经历一较长时间达到矮小 (stunted),矮小是生长迟缓的最终结果,即发生 矮小有较长的时间。生长迟缓为Ⅱ类营养素(生 长营养素)中蛋白质以及相关营养素较长时间缺 乏所致。因此,近年已将儿童生长迟缓视为“持 续营养不良状态” [10] 。

|

图 1 体重、身高、体重/身高的关系 |

过去通过体格生长水平检测获得5岁以下儿 童人群中营养不良的流行特征,或为趋势、状况 的描述,结果用流行率(患病率)表示,如中 (重)度低体重患病率=调查儿童的中(重)度 低体重人数/调查儿童总数(%)。近年WHO以 儿童人群体重/身高的状况作为儿童人群营养不良 流行强度判断标准 [5] 。若5%~10%的儿童体重/身 高<2 SD为该儿童人群存在中度急性营养不良, 若>10%儿童的体重/身高<2 SD,则该儿童人群 存在严重营养不良 [21] 。

营养不良时体格检查结果有不定因素,如体 征的非特异性,即同一体征可同时存在几种营养 素缺乏;或多个体征共存在营养素缺乏;或双向 体征(bi-directional signs),即体征可在疾病初出现, 也可在恢复期出现,如肝大可在蛋白质-能量营 养不良时发生,也可在治疗中出现。此外,还存 在检查者的不一致性以及体征可变性等情况 [12] 。

尽管实验室结果可用于个体儿童营养不良状 况的评价,但近年的研究提示这些方法不是营养不 良的准确指标,对儿童营养不良的诊断无特异性。 临床上往往在没有实验室结果前营养不良已被训 练有素的医生结合体格发育资料进行诊断。因此, 营养不良的实验室检查尚需进行成本-效益评估。 重度营养不良儿童的生化指标的改变多帮助医生 了解儿童全身各器官系统的功能状态,监测对治疗 的反应,或评估住院儿童出院前的营养状况。

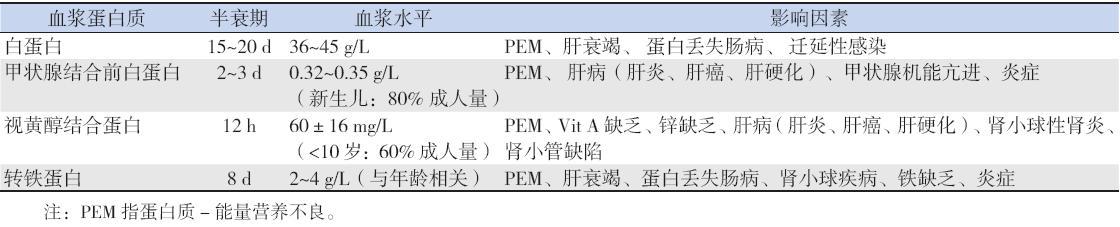

营养不良儿童的一般筛查试验包括血液学检 查及蛋白质营养状况、器官功能测试(表1)。 严 重营养不良儿童因食物摄入不足除Ⅱ类生长营养 素缺乏外,尚伴Ⅰ类功能性营养素缺乏,如铁、维 生素A、维生素B、维生素B12缺乏。医生可根据 临床表现进行特殊维生素和微量元素检测。经典的 生化检查为检查血、尿或其他标本中的营养素,如 视黄醇;或代谢产物,如烟酸在尿中的代谢产物N- 甲基烟酰胺;或生化功能试验,维生素B1与B2作 为红细胞的酶的活性;或出现异常代谢产物,如叶 酸缺乏时同型半胱氨酸量;或负荷试验,如口服大 剂量维生素C后检查尿中含量;其他方法,如稳 定同位素方法检查等 [12] 。生化检查有时仅能提示 部分结果,如血红蛋白低提示贫血,但贫血亦可与 铁缺乏或感染有关,特别是疟疾、钩虫病,或遗传 性血液病,如镰状细胞贫血、地中海贫血。

| 表 1常用血浆蛋白营养评估参数[12] |

上世纪中曾用羟脯氨酸指数,即羟脯氨酸 (μmol/mL)/肌酐(μmol/mL·kg)比值评估营养不良 儿童蛋白质营养状况 [22] 。近年也有学者研究采用瘦 素作为一个营养指标,但尚没有广泛应用于临床 [23, 24] 。

(1)中度营养不良营养处理:2005年母 亲儿童营养不良工作组(the Maternal and Child Malnutrition Study Group,MCUSG)以WHO儿童体 格生长标准分析139个低收入国家的388个研究资 料的5.56亿5岁以下儿童中有5500万消瘦儿童, 2/3(3600万)为中度消瘦,1/3(35%,1900万) 为严重消瘦 [25] ,同时中度营养不良如不及时干预 可发展为严重营养不良 [9] 。多年来国际上治疗严重 营养不良已有较成熟的一致意见,而治疗以谷类 食物不足为主的中度营养不良婴幼儿的成本-效 益方面亦未统一 [9, 26] 。因此干预、预防中度营养不 良是提高全球儿童健康水平的关键。2008年10月 WHO、联合国儿童基金会(UNICEF)、联合国世 界粮食计划署(WFP)、联合国难民事务高级专 员(办事处)(UNHCR)联合召开关于5岁以下 儿童中度营养不良的饮食干预的专题研讨会 [27] 。 目前尚无为中度营养不良儿童制定的营养素推荐 摄入量,但多数推荐其营养素摄入量介于正常儿 童推荐摄入量与严重营养不良儿童之间 [10] ,WHO 建议补充特殊配制的食物,如以奶粉为基础配制 的F75、F100配方 [12] ,同时采用当地食物,以保 证食物摄入Ⅰ类(功能性、预防性营养素)和Ⅱ 类(生长营养素)等30余种营养素,使儿童加速 生长至正常水平 [10] 。目前,已有商品F75、F100(表2) 用于治疗中度营养不良 [28] ,国内尚无商品F75。

| 表 2商品F100成分* |

治疗中度营养不良恰当的表现为儿童体重增 加率约为5.5 g/kg·d。但体重的增加不代表机体生 理、生化、免疫功能和解剖结构恢复正常,身高 的增长比体重的增加能更好地反映营养不良儿童 是否获得适当的营养 [10] 。消瘦和矮小儿童的营养 需要不同,康复时间亦不同。中度消瘦儿童需治 疗2~4周恢复,而矮小儿童恢复到正常儿童水平 则需数月或数年。因此,生长迟缓的儿童应尽早 治疗,2岁内是治疗的“窗口关键”期。

(2)重度营养不良处理:F-75和F-100亦用 于治疗严重营养不良儿童。为避免肠道负荷过多, 宜由少量逐渐增加致耐受 [29] ;无法耐受者需采用肠内营养方法。

近年报道给低体重儿童增加食物能量的研究 结果显示有增加超重/肥胖的儿童的危险 [20] 。为 纠正24~36月龄严重营养不良儿童的生长迟缓时 补充高蛋白、高能量,但往往因补充过度出现体 重增长过多情况。因此,宜以体重/身高为标准评 估,决定是否需继续补充营养,避免发生治疗后 的超重/肥胖 [12] 。

虽然评估食物微量营养素可提示潜在的微量 营养素缺乏,生化检查亦可较客观获得资料,但 临床实际中并不能常规获得。因部分微量营养素 的概念难以确定,生化检查结果可包括摄入部分 与身体贮存两部分内容,检查结果难以区分二者。因此,临床评估微量元素难以进行,缺乏全球一 致的可靠和微量营养素生物学检测 [30] 。2010年2 月国立儿童健康与人类发展研究所(NICHD)、 美国国立卫生研究院(NIH)、美国卫生和人类 服务部(HHS)组织一关于“发展营养生物标记 建立共识”的研讨会(Biomarkers of Nutrition for Development:Building a Consensus) [31] ,确定发展 营养生物标记的方案(The BOND program),研究 营养素的生物标记物,即一个人摄入多少营养素、 机体需要多少营养素、体内状况(缺乏或过多)、 功能以及治疗与干预的反应等。目前正在研究的 微量营养素有叶酸、碘、铁、维生素A、维生素 B12、锌6种 [32] 。

全世界约5%~15%的儿童消瘦,多发生在 6~24月龄;20%~40%儿童2岁时仍矮小 [10] 。以 证据为基础的干预和治疗营养不足的成本效益分 析结果显示胎儿期和生后24月龄是最高的投资 回报率的关键期。有资料显示发展中国家儿童发 生营养不良的年龄为3月龄至18~24月龄 [33] 。人 力资本(human capital)核心是提高人口质量与 教育,最好的预测因子是2岁时的身高 [10] 。儿童 期营养不足的后果是低的人力资本。因此,理想 的婴幼儿喂养对儿童的生长非常重要,生后2年 是预防儿童生长落后的关键期(critical window of opportunity)。

近年的研究已证实蛋白质、能量充足时可满 足微营养素的需要,即玉米、大米、小麦、豆子、 水果、蔬菜等含有所有微营养素而不需要另外补 充。因此,低收入国家营养政策应有重要改变, 以促进以食物为基础的研究代替现在微营养素补 充或强化食物的政策 [34] 。预防的关键是提高家长 的营养知识,改变喂养儿童的行为。

| [1] | Maqbool A. Clinical assessment of nutritional status[M/OL]//Nutrition in Pediatrics. 4th ed. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: BC Decker Inc, 2008. [October 7, 2013]. http://anhi.org/learning/pdfs/bcdecker/Clinical_Assessment_of_Nutritional_Status.pdf. |

| [2] | Elamin A. Assessment of nutritional status[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. www.pitt.edu/~super7/19011-20001/19801.ppt. |

| [3] | Quandt SA. Assessment of nutritional status[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.answers.com/topic/assessment-of-nutritional-status. |

| [4] | Academy Medical.com. Laboratory assessment of nutritional status [EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.academymedical.com/past_Web_Lab-Assessment-Nutritional-Status.asp#1). |

| [5] |

Blossner M, de Onis M. Malnutrition: quantifying the health impact at national and local levels. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2005. WHO Environmental Burden of Disease Series, No. 12 [EB/OL].[October 7, 2013]. http://search.yahoo.com/search;_ylt=ApPc978eWRs_cH0tmuX1AbSbvZx4?p=Bl%C3%B6ssner%2C+Monika%2C+de+Onis%2C+Mercedes.+Malnutrition%3A+quantifying+the+health+impact+at+ +national+and+local+levels.&toggle=1&cop=mss&ei=UTF-8&fr=yfp-t-901. |

| [6] | 黎海芪, 毛萌. 儿童保健学[M]. 第2版. 北京:人民卫生出版社, 2009. |

| [7] | Allen LH, Gillespie SR. What works? A review of the efficacy and effectiveness of nutrition interventions[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.unsystem.org/SCN/archives/npp19/index.htm. |

| [8] | Fomon SJ. Assessment of growth of formula-fed infants: evolutionary considerations (Secial article)[J]. Pediatrics, 2004, 113(2): 389-393. |

| [9] | Ashworth A. WHO Technical Background Paper: Dietary counselling in the management of moderately malnourished children. the WHO, UNICEF, WFP and UNHCR Consultation on the Dietary Management of Moderate Malnutrition in Under-5 Children by the Health Sector September 30th October 3rd, 2008[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/MM_consultation_background.pdf. |

| [10] | Golden MH. Proposed recommended nutrient densities for moderately malnourished children[J]. Food Nutr Bull, 2009, 30(3 Suppl): S267-S342. |

| [11] | Prentice AM, Gershwin ME, Schaible UE, et al. New challenges in studying nutrition-disease interactions in the developing world[J]. J Clin Invest, 2008,118(4):1322-1329. |

| [12] | Avencena IT, Cleghorn G. The nature and extent of malnutrition in children. Nutrition in the infant: Problems and practical procedures[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. www.cambridge.org. |

| [13] | DFyk MK. Malnutrition[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.answers.com/topic/malnutrition. |

| [14] | Malnutrition From Wikipedia[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Child_malnutrition. |

| [15] | O' Sullivan A, Sheffrin SM. Economics: Principles in Action[M]. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2003: 481. |

| [16] | WHO/WFP/UNHCR informal consultation on the management of moderate malnutrition in under-5 children[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. Food Nutr Bull, 2009. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/MM_consultation_background.pdf. |

| [17] | Shrimpton R, Victora CG, de Onis M, et al. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: implications for nutritional interventions[J]. Pediatrics, 2001, 107(5): E75. |

| [18] | WHO child growth standards and the identifcation of severe acute malnutritionin infants and children. A Joint Statement by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children's Fund[EB/OL]. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/severema lnutrition/9789241598163_eng.pdf. |

| [19] | Prudhon C, Briend A, Prinzo ZW. WHO, UNICEF, and SCN Informal Consultation on Community-Based Management of Severe Malnutrition in Children[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.unscn.org/layout/modules/resources/files/Policy_paper_No_21.pdf. |

| [20] | Uauy R, Rojas J, Corvalan C, et al. Prevention and control of obesity in preschool children: importance of normative standards[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2006 (Suppl 3): S26-S37. |

| [21] | Pellett P, Ghosh S. Global nutritional problems with special attention to the role of animal foods in human nutrition. WHO, UNICEF, WFP, UNHCR. Proceedings of the WHO/UNICEF/WFP/UNHCR informal consultation on the management of moderate malnutrition in under-5 children[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/MM_consultation_background.pdf. |

| [22] | Scheinfeld NS, James WD. The WHO recommends the following laboratory tests: laboratory studies[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104623-workup. |

| [23] | Malnutrition[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://labtestsonline.org/understanding/conditions/malnutrition/start/2. |

| [24] | 张苏江, 单安山. 营养状况与瘦素水平研究进展[J]. 中国公共卫生, 2008, 24(2):236-238. |

| [25] | Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences[J]. Lancet, 2008, 371(3608):243-260. |

| [26] | Michaelsen KF, Hoppe C, Roos N, et al. Choice of food and ingredients for moderately malnourished children 6 months to 5 years of age[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/moderate_malnutrition/FNBv30n3_suppl_paper2.pdf. |

| [27] | Briend A, Prinzo ZW. Dietary management of moderate malnutrition: time for a change[J]. Food Nutr Bull, 2009, 30(Suppl 3): S265-S266. |

| [28] | F-75-Phase 1 therapeutic milk[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.msi-germany.com/en/therapeutic_food-f75.html. |

| [29] | Howard C. Protein energy malnutrition[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.mayo.edu/mayo-edu-docs/mayo-school-of-graduate-medical-education-documents/ProteinEnergyMalnutrition_Howard.ppt. |

| [30] | Seal A, Prudhon C. Nutrition Information in Crisis Situations. Assessing micronutrient deficiencies emergencies. Current practice and future directions[M]. United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition, 2007. |

| [31] | Raiten DJ, Namaste S, Brabin B, et al. Executive summary--biomarkers of nutrition for development: building a consensus[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2011, 94(2): 633S-650S. |

| [32] | NIH effort seeks to identify measures of nutritional status[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.nih.gov/news/health/jul2011/nichd-06.html. |

| [33] | Programming Guide: Infant and Young Child Feeding. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF)[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.unicef.org/nutrition/files/Final_IYCF_programming_guide_2011.pdf. |

| [34] | Ruel MT. Can food-based strategies help reduce vitamin A and iron deficiencies? A review of recent evidence. International Food Policy Research Institute. Washington, D.C.2001[EB/OL]. [October 7, 2013]. http://www.idpas.org/pdf/847CanFoodbased.pdf. |

2014, Vol. 16

2014, Vol. 16