钙 卫 蛋 白(calprotectin) 最 早 由 Fagerhol 于 1980 年从中性粒细胞中分离发现,是一种杂 合性的钙结合蛋白,属于S-100 族,分子量为 36.5 kDa,由 两 条 重 链 MRP14(8-kDa,S100A8/ L1L/p8/CP-10 和 14-kDa,S100A9/L1H/p14) 和 一 条轻链 MRP8 非共价结合形成的异二聚体,每条 链可结合两个钙离子,具有螯合锌的能力而具有 抗热性,在钙离子存在的情况下还具有抗蛋白酶 活性。此外,钙卫蛋白还具有参与细胞信号传导、 维持细胞骨架、诱导细胞凋亡、抑制微生物(如 细菌、真菌)活性及其增殖、免疫调节、抑制基 质金属酶活性等生物学功能[1]。

钙卫蛋白广泛分布于人体细胞、血浆、尿液、 粪便、脑脊液、唾液、滑膜液以及结肠等组织及 体液中,是构成中性粒细胞、巨噬细胞的主要蛋 白质。钙卫蛋白是一种有效的中性粒细胞趋化因 子,血浆、粪便中的钙卫蛋白含量均与中性粒细 胞数量呈正相关[2]。体内发生炎症反应时,血浆钙 卫蛋白水平升高,甚至达到正常的 5~40 倍。然而, 由于健康成年男性的血浆钙卫蛋白水平明显高于 女性,存在明显的性别差异,并受到体内各系统 炎症的影响,因而不能特异地反映肠道炎症[2]。 与此不同的是,当肠道内炎症发生时,中性粒细 胞穿过肠壁进入肠腔,导致粪钙卫蛋白(faecal calprotectin, FC)水平升高。FC 水平可达到血浆水 平的 6 倍左右,且无性别差异[2,3];并且与 111 铟 标记的中性粒细胞排出量呈正相关[2],因此 FC 能 更特异、敏感地反映肠道炎症。

大量研究发现,FC 是一个筛查、诊断和监测 肠道炎症的敏感而非侵袭性的指标[4],尤其适用 于血液采集困难的儿童。FC 的理化性质稳定,用 普通收集盒留取粪便后在常温下可保存 1 周,或 者 -20℃冷冻储存长达 6 个月,其生物活性不改变; 此外,随机采集 <5 g 的粪便样本显示的钙卫蛋白 浓度与收集 24 h 粪便样本均质化后检测的钙卫蛋 白浓度相同,表明钙卫蛋白均匀地分散在整个粪 便中[4],这些特性均有利于样本的收集和检测。 FC 检测最先采用酶联免疫法(ELISA);2000 年 经改良后,其检测所需样本量仅为 50~100 mg,并 具有检测灵敏性高、快速、简便,可重复性高等 特点[5]。目前大多数研究采用 PhiCaTest(Eurospital) 或 Calprest(Nycomed) 试 剂 盒 或 Bühlmann 公 司 生产的试剂盒,其提供的正常参考值为成人以及 4~17 岁儿童青少年的 FC 水平正常上限为 50 μg/g, 无性别差异[3,5,6,7]。然而,儿童,尤其是新生儿及婴 幼儿的 FC 水平明显高于成人,目前还未有比较统 一的 FC 水平正常上限。本文就 FC 与婴幼儿肠道 发育及相关疾病的研究进展做一综述。 1 儿童 FC 与肠道发育相关性及影响因素

儿童期 FC 水平增高,尤其是新生儿及婴幼儿 FC 水平增高,反映其肠道中的中性粒细胞数量增 加,这可能是由于婴幼儿肠道上皮细胞紧密连接 和其他免疫因素发育不成熟而使肠道通透性增高, 导致迁移至肠腔的中性粒细胞或者巨噬细胞增加 所致[8,9]。在出生后的前几周内开始出现的肠道菌 群定植,以及由肠道菌群产生的趋化物质,如甲 酰甲硫亮氨酰苯丙氨酸(formyl-methionyl-leucylphenylalanine, FMLP),可能刺激中性粒细胞跨内 膜上皮细胞而迁移至肠腔内,导致 FC 水平增加[9]。 此外,在婴幼儿特定生理时期 FC 水平增高也可能 是作为肠道相关淋巴组织(gut-associated lymphoid tissue, GALT)正常发育的一部分 [10]。随着年龄增长, 肠道黏膜逐渐发育成熟,婴幼儿的 FC 水平逐步下 降[9,11,12]。因此一些决定肠道发育的因素也就影响 着婴幼儿的 FC 水平,如年龄、分娩方式、喂养方 式、疾病等。 1.1 年龄

年龄是影响婴幼儿 FC 水平的一个重要因素, <1 岁婴儿,尤其是3 个月内婴儿的FC 水平较 高,且表现出较大的个体差异。研究发现,新生 儿出生 3 d 内排出的胎粪的 FC 就处于高水平 [13]。 2003 年 Laforgia 等 [14] 最先报道胎粪FC 水平,平 均为 145.2 ±78.5 μg/g,明显高于成人水平,并 与新生儿出生体重、出生胎龄、5 分钟 Apgar 评 分相关,而与性别、分娩方式、母亲状况无关。 在另两项早产 / 极低出生体重儿的研究中,无任 何胃肠道异常表现的早产 / 极低出生体重儿的胎 粪 FC 水平平均数及中位数分别为 178.1 μg/g [13] 、 332(12~9 386)μg/g [15]。新生儿期的FC继续处 于高水平,大多数研究均报道新生儿期的 FC 的 平均水平或中位数在150~250 μg/g 之 间 [16,17,18]。 1~3 个月婴儿的 FC 仍持续处于高水平,维持在 200~300 μg/g [9-10,14,19-20 ];3 个月以后至1 岁的婴儿 FC 水平逐渐下降,维持在100 μg/g 左右 [21,22,23]; 1 岁后继续下降,4 岁以上则与成人基本一致 [22]。 本课题组调查我国上海市婴幼儿 FC 水平发现, 6 月龄时中位数为 139.5(26.2~1 257.6)μg/g,9 月 龄为 110.4(10.0~ 2 777.7)μg/g,12 月龄为 116.5 (10.0~2 058.0)μg/g,18 月龄为 104.2(6.0~937.5) μg/g [24],均高于健康成人的正常水平,且随着年龄 增长 FC 水平有降低趋势。目前有关正常婴幼儿 FC 水平的研究均属于横断面研究,或局限于某一 年龄段的短期随访,尚缺乏对婴幼儿 FC 水平的长 期纵向随访研究。由于各项研究中研究对象的年 龄不一致,FC 随年龄变化明显、个体变异大,且 研究较少以及研究数据表达不一致,目前还不能 对婴幼儿 FC 水平进行 Meta 分析。 1.2 早产 / 低出生体重

由于消化系统生理和神经内分泌调节机能不 成熟,早产 / 低出生体重儿与足月儿相比,其胃肠 道结构、功能,肠道免疫屏障和菌群尚不完善, 更易出现喂养不耐受、新生儿坏死性小肠结肠炎 (NEC)等相关疾病,因此早产 / 低出生体重儿的 FC 水平变化引起人们的关注。但研究发现,虽然 早产/ 低出生体重儿的肠道黏膜渗透性明显升高[25], 但其 FC 水平与足月儿相比并无明显差异[8,11,16]。 关于早产 / 低出生体重儿 FC 水平的变化,文献报 道也不一致,但其与足月儿一样,呈现出随年龄 逐渐下降的趋势[11,15,16,26,27,28,29]。有少数研究报道,早 产 / 低出生体重儿的 FC 水平与肠内喂养量、产后 日龄、出生胎龄成正比,与体重增加成反比[11]。 1.3 母亲及出生前因素

由于母亲分娩前应用抗生素影响其胎儿出生 后肠道菌群的建立,不同的分娩方式也影响新生 儿肠道菌群的建立,因此母亲及出生前因素对新 生儿及婴儿的 FC 水平也有一定的影响。

研究证实,母亲分娩前应用抗生素的早产儿, 其胎便 FC 水平明显低于未用抗生素治疗者,同时 发现粪便中葡萄球菌及杆菌数量与 FC 水平呈正相 关[16]。有关不同分娩方式对 FC 究竟产生怎样的影 响仍未达成一致的意见。

研究显示,阴道分娩新生儿的胎粪 FC 水平平 均为 144.7 μg/g,低于剖宫产新生儿为 162.3 μg/g, 但差异无统计学意义[14]。早产 / 低出生体重儿胎 粪 FC 水平与分娩方式无关,但多元回归显示 0~8 周的剖宫产早产 / 低出生体重儿的 FC 水平较高[15]。 1.4 早期喂养

不同的早期喂养方式影响新生儿肠道菌群建 立、肠道通透性等,因此早期喂养对新生儿、婴 儿 FC 水平应该有一定程度的影响。但目前对不同 早期喂养方式如何影响早产儿及足月儿 FC 水平仍 存在着争议。大多数研究发现,纯母乳喂养新生 儿及婴儿的 FC 水平高于配方奶喂养或混合喂养的 婴儿[10,21]。其原因可能是由于母乳能促进婴儿胃肠 黏膜的生长,能减少肠道的通透性;母乳喂养婴 儿产生的益生菌(双歧杆菌和乳酸杆菌)刺激肠 道相关淋巴组织正常的发育(导致钙卫蛋白分泌 增加)、IgA 的合成与分泌及平衡辅助 T 细胞的应 答,成为出生后免疫系统成熟的主要外来驱动因 素;而且母乳本身能够通过细胞因子、激素及其 他免疫刺激因子及生长因子(如胃促生长素、瘦素、 胰岛素样生长因子、表皮生长因子、粒细胞集落 刺激因子)调节肠道免疫系统的发育,促进肠道 黏膜的发育从而影响着 FC 水平[10,30];另外 FC 水 平升高可能通过其杀菌及抑菌作用而对肠道黏膜 产生保护,也有利于调节母乳喂养婴儿的肠道菌 群[10,21]。关于不同喂养方式对 FC 影响的具体机制 还需进一步的深入研究。与此同时,在对早期喂 养的研究中也发现,肠内喂养耐受差的新生儿或 婴儿,其 FC 水平异常升高,有研究者提出可以检 测 FC 水平预测肠内喂养不耐受[11]。 1.5 其他因素

研究显示,其他一些因素,如口服益生菌也 影响婴儿的 FC 水平[31]。婴幼儿时期的一些特定的 疾病,如特应性皮炎、牛奶蛋白过敏、胃食管反 流等也会影响到婴幼儿的 FC 水平[32]。 2 FC 与肠道疾病相关研究 2.1 NEC

NEC 确切的病因还并不完全清楚,目前多认 为是由早产、感染及其炎症反应、缺氧缺血、喂 养不当等多种因素综合作用而引起。NEC 是新生 儿期最常见的肠道急症,活产婴中发病率约为 1%, 早产 / 极低体重儿发病率达 7%。NEC 新生儿 FC 水平异常增高[28,33,34],且随着疾病进展 FC 水平持 续增加,FC 水平与 NEC 严重程度相关,而在治疗 后伴随着病情缓解,FC 水平也逐渐下降[1]。因此 有研究者提出 FC 可作为 NEC 诊断、随访的有用 的生物标记物[1,28]。

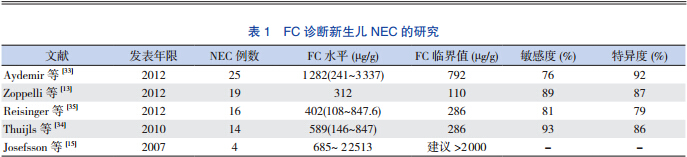

然而,由于健康足月儿和早产儿的 FC 水平 高,且存在很大的个体差异[8,16,17]。故 FC 鉴别诊 断 NEC 及非 NEC 新生儿临界值难以确定。不同的 研究者在不同的研究中提出了不同的临界值,也 有着各自不同的灵敏度和特异度,见表 1。但同样 由于研究对象的差异,数据不足等原因,难以进 一步进行 Meta 分析。

| 表 1 FC 诊断新生儿 NEC 的研究 |

此外,也有一些研究者认为,FC 并不能在早 期帮助诊断 NEC,而只能在疾病后期帮助确定诊 断[36]。对于 FC 在 NEC 诊断及治疗过程的作用仍 需要前瞻性研究作进一步的探讨。 2.2 炎症性肠病

炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease)是指 原因不明的一组非特异性慢性胃肠道炎症性疾病, 包括溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis)、克罗恩病 (Crohn's disease)和未定型结肠炎(indeterminate colitis)。FC 检测在炎症性肠病患儿中应用最为广 泛,不仅为诊断提供依据,同时也可评价疾病严 重程度,评价药物疗效以及监测疾病是否复发。 有关 FC 在儿童炎症性肠病诊断、治疗及对复发预 测等方面的作用,近期已有多篇综述[37,38,39]。

虽然 FC 在评估炎症性肠病中是一种价廉、简 便、特异及敏感的检测方法,在炎症性肠病诊断、 随访、复发的评估、治疗反应中也起着重要的作用, 但是 FC 不能作为器质性病变的标记物,只能作为 肠道炎症的标记物而被用作一种补充的检测方法。 目前需要更多的研究来证明 FC 在诊断和治疗炎症 性肠病中的作用。 2.3 肠道感染

FC 也被用于帮助鉴别肠道感染性腹泻的严重 程度、鉴别细菌性或者病毒性肠炎及鉴别重度持 续性腹泻的致病因素[12,40,41]。

研究发现,FC 与腹泻严重程度相关[40],中重 度腹泻患儿的 FC 水平较轻度腹泻患儿明显升高, FC 水平随着疾病的严重程度而增加。

在不同病原体所致的腹泻中,沙门菌、弯曲 杆菌感染患儿的 FC 水平明显高于轮状病毒、诺沃 克类病毒或腺病毒感染患儿[40]。总体上,病毒感 染所致腹泻患儿的 FC 水平略有增高,而细菌感染 腹泻患儿的 FC 水平则是明显升高,因而研究者提 议,可以通过检测 FC 水平而鉴别细菌性或病毒性 腹泻。

在鉴别重度持续性腹泻患儿的致病因素时, 自身免疫性肠病及炎症性结肠炎患儿的 FC 水平异 常升高,远高于原发性肠上皮病变引起腹泻的患 儿;有研究者认为,在鉴别原发性肠上皮病变和 免疫 - 炎症性病变导致的严重腹泻中,FC 的敏感 度、特异度、阴性预测值均可达到 100%[41]。 2.4 乳糜泻

乳糜泻是一种具有遗传性的发生于小肠的自 身免疫性疾病,是由遗传和环境相互作用引起的, 这种自身免疫性疾病可导致小肠黏膜损伤 ,引起肠 黏膜炎症发生及肠道通透性增加,导致 FC 水平增 加[42,43]。研究证实,乳糜泻患儿 FC 水平增高,且 FC 水平与其组织病理学的严重程度相关,而经过 无麸质饮食治疗后,患儿的 FC 水平明显下降[43]。 因此,检测 FC 水平有助于从功能性胃肠功能紊乱 疾病中鉴别乳糜泻。但乳糜泻疾病患儿 FC 水平升 高的机制、具体的作用还需进一步研究。 2.5 过敏及其他

FC 也被逐步应用在其他胃肠道疾病中,如食 物过敏、胃食管反流、肠息肉病、活动性隐窝炎、 功能性便秘、功能性腹痛、肠易激综合征、喂养 不耐受等。研究发现,食物过敏儿童的 FC 是非过 敏儿童的 2 倍[44];牛奶蛋白过敏婴儿经深度水解 配方奶喂养1 个月后,随着胃肠道症状改善及消失, FC 水平也显著下降 [23]。此外,研究显示胃食管反流、 肠息肉病、活动性隐窝炎、过敏性结肠炎患儿的 FC 水平也明显升高,而在经过饮食调整等治疗后, FC 水平降至正常 [45]。 3 结语

总之,FC 是急性和慢性肠道炎症的一种重要 的炎症介质,其在儿科胃肠道疾病中的作用正逐 步受到重视。FC 检测相对于其他评估胃肠道疾病 的方法有较高的敏感性及特异性,但到目前为止 FC 只是作为一种补充性的检测。尽管 FC 有很多 可能的生物功能,但其在儿科肠道疾病中的生物 作用机制仍然不清楚。婴幼儿 FC 水平的正常值及 其影响因素也有待进一步确认。因此需要更多的 前瞻性研究,进一步阐明 FC 在儿科各种生理或病 理状态下的临床意义。

| [1] | Vaos G, Kostakis ID, Zavras N, et al. The role of calprotectin inpediatric disease[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2013, 2013: 542363. |

| [2] | Roseth AG, Schmidt PN, Fagerhol MK. Correlation betweenfaecal excretion of indium-111-labelled granulocytes andcalprotectin, a granulocyte marker protein, in patients withinflammatory bowel disease[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 1999,34(1): 50-54. |

| [3] | Fagerberg UL, Loof L, Merzoug RD, et al. Fecal calprotectinlevels in healthy children studied with an improved assay[J]. JPediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2003, 37(4): 468-472. |

| [4] | Turkay C, Kasapoglu B. Noninvasive methods in evaluationof inflammatory bowel disease: where do we stand now? Anupdate[J]. Clinics (Sao Paulo), 2010, 65(2): 221-231. |

| [5] | Ton H, Brandsnes, Dale S, et al. Improved assay for fecalcalprotectin[J]. Clin Chim Acta, 2000, 292(1-2): 41-54. |

| [6] | Gisbert JP, McNicholl AG. Questions and answers on the role offaecal calprotectin as a biological marker in inflammatory boweldisease[J]. Dig Liver Dis, 2009, 41(1): 56-66. |

| [7] | Fagerberg UL, Loof L, Myrdal U, et al. Colorectal inflammationis well predicted by fecal calprotectin in children withgastrointestinal symptoms[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr,2005, 40(4): 450-455. |

| [8] | Kapel N, Campeotto F, Kalach N, et al. Faecal calprotectin interm and preterm neonates[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr,2010, 51(5): 542-547. |

| [9] | Olafsdottir E, Aksnes L, Fluge G, et al. Faecal calprotectin levelsin infants with infantile colic, healthy infants, children withinflammatory bowel disease, children with recurrent abdominalpain and healthy children[J]. Acta Paediatr, 2002, 91(1): 45-50. |

| [10] | Savino F, Castagno E, Calabrese R, et al. High faecalcalprotectin levels in healthy, exclusively breast-fed infants[J].Neonatology, 2010, 97(4): 299-304. |

| [11] | Rouge C, Butel MJ, Piloquet H, et al. Fecal calprotectinexcretion in preterm infants during the neonatal period[J]. PLoSOne, 2010, 5(6): e11083. |

| [12] | Sykora J, Siala K, Huml M, et al. Evaluation of faecalcalprotectin as a valuable non-invasive marker in distinguishinggut pathogens in young children with acute gastroenteritis[J].Acta Paediatr, 2010, 99(9): 1389-1395. |

| [13] | Zoppelli L, Guttel C, Bittrich HJ, et al. Fecal calprotectinconcentrations in premature infants have a lower limit and showpostnatal and gestational age dependence[J]. Neonatology,2012, 102(1): 68-74. |

| [14] | Laforgia N, Baldassarre ME, Pontrelli G, et al. Calprotectinlevels in meconium[J]. Acta Paediatr, 2003, 92(4): 463-466. |

| [15] | Josefsson S, Bunn SK, Domellof M. Fecal calprotectin in verylow birth weight infants[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2007,44(4): 407-413. |

| [16] | Nissen AC, van Gils CE, Menheere PP, et al. Fecal calprotectinin healthy term and preterm infants[J]. J Pediatr GastroenterolNutr, 2004, 38(1): 107-108. |

| [17] | Campeotto F, Butel MJ, Kalach N, et al. High faecal calprotectinconcentrations in newborn infants[J]. Arch Dis Child FetalNeonatal Ed, 2004, 89(4): F353-355. |

| [18] | Baldassarre ME, Altomare MA, Fanelli M, et al. Doescalprotectin represent a regulatory factor in host defense or adrug target in inflammatory disease?[J]. Endocr Metab ImmuneDisord Drug Targets, 2007, 7(1): 1-5. |

| [19] | Rhoads JM, Fatheree NY, Norori J, et al. Altered fecalmicroflora and increased fecal calprotectin in infants withcolic[J]. J Pediatr, 2009, 155(6): 823-828. |

| [20] | Rosti L, Braga M, Fulcieri C, et al. Formula milk feeding doesnot increase the release of the inflammatory marker calprotectin,compared to human milk[J]. Pediatr Med Chir, 2011, 33(4):178-181. |

| [21] | Dorosko SM, Mackenzie T, Connor RI. Fecal calprotectinconcentrations are higher in exclusively breastfed infantscompared to those who are mixed-fed[J]. Breastfeed Med, 2008,3(2): 117-119. |

| [22] | Hestvik E, Tumwine JK, Tylleskar T, et al. Faecal calprotectinconcentrations in apparently healthy children aged 0-12 years inurban Kampala, Uganda: a community-based survey[J]. BMCPediatr, 2011, 11: 9. |

| [23] | Baldassarre ME, Laforgia N, Fanelli M, et al. LactobacillusGG improves recovery in infants with blood in the stoolsand presumptive allergic colitis compared with extensivelyhydrolyzed formula alone[J]. J Pediatr, 2010, 156(3): 397-401. |

| [24] | 张杰, 刘金荣, 盛晓阳, 等. 6-18 月龄婴幼儿粪钙卫蛋白水平及其变化趋势[J]. 肠外与肠内营养, 2012, 19(4): 214-217. |

| [25] | Taylor SN, Basile LA, Ebeling M, et al. Intestinal permeabilityin preterm infants by feeding type: mother's milk versusformula[J]. Breastfeed Med, 2009, 4(1): 11-15. |

| [26] | Campeotto F, Kalach N, Lapillonne A, et al. Time course offaecal calprotectin in preterm newborns during the first month oflife[J]. Acta Paediatr, 2007, 96(10): 1531-1533. |

| [27] | Campeotto F, Baldassarre M, Butel MJ, et al. Fecal calprotectin:cutoff values for identifying intestinal distress in preterminfants[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2009, 48(4): 507-510. |

| [28] | Carroll D, Corfield A, Spicer R, et al. Faecal calprotectinconcentrations and diagnosis of necrotising enterocolitis[J].Lancet, 2003, 361(9354): 310-311. |

| [29] | Yang Q, Smith PB, Goldberg RN, et al. Dynamic change offecal calprotectin in very low birth weight infants during the firstmonth of life[J]. Neonatology, 2008, 94(4): 267-271. |

| [30] | Westerbeek EA, Morch E, Lafeber HN, et al. Effect of neutraland acidic oligosaccharides on fecal IL-8 and fecal calprotectinin preterm infants[J]. Pediatr Res, 2011, 69(3): 255-258. |

| [31] | Mohan R, Koebnick C, Schildt J , e t al. Effects ofBifidobacterium lactis Bb12 supplementation on body weight,fecal pH, acetate, lactate, calprotectin, and IgA in preterminfants[J]. Pediatr Res, 2008, 64(4): 418-422. |

| [32] | Baldassarre ME, Fanelli M, Lasorella ML, et al. Fecalcalprotectin (FC) in newborns: is it a predictive marker ofgastrointestinal and/or allergic disease?[J]. ImmunopharmacolImmunotoxicol, 2011, 33(1): 220-223. |

| [33] | Aydemir O, Aydemir C, Sarikabadayi YU, et al. Fecal calprotectin levels are increased in infants with necrotizingenterocolitis[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2012, 25(11):2237-2241. |

| [34] | Thuijls G, Derikx JP, van Wijck K, et al. Non-invasive markersfor early diagnosis and determination of the severity ofnecrotizing enterocolitis[J]. Ann Surg, 2010, 251(6): 1174-1180. |

| [35] | Reisinger KW, Van der Zee DC, Brouwers HA, et al.Noninvasive measurement of fecal calprotectin and serumamyloid A combined with intestinal fatty acid-binding protein innecrotizing enterocolitis[J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2012, 47(9): 1640-1645. |

| [36] | Selimoglu MA, Temel I, Yildirim C, et al. The role of fecalcalprotectin and lactoferrin in the diagnosis of necrotizingenterocolitis[J]. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2012, 13(4): 452-454. |

| [37] | Kallel L, Fekih M, Boubaker J, et al. Faecal calprotectin ininflammatory bowel diseases: review[J]. Tunis Med, 2011,89(5): 425-429. |

| [38] | Kostakis ID, Cholidou KG, Vaiopoulos AG, et al. Fecalcalprotectin in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: asystematic review[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2013, 58(2): 309-319. |

| [39] | Waugh N, Cummins E, Royle P, et al. Faecal calprotectin testingfor differentiating amongst inflammatory and non-inflammatorybowel diseases: systematic review and economic evaluation[J].Health Technol Assess, 2013, 17(55): 1-212. |

| [40] | Chen CC, Huang JL, Chang CJ, et al. Fecal calprotectin as acorrelative marker in clinical severity of infectious diarrheaand usefulness in evaluating bacterial or viral pathogens inchildren[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2012, 55(5): 541-547. |

| [41] | Kapel N, Roman C, Caldari D, et al. Fecal tumor necrosisfactor-alpha and calprotectin as differential diagnostic markersfor severe diarrhea of small infants[J]. J Pediatr GastroenterolNutr, 2005, 41(4): 396-400. |

| [42] | Balamtekin N, Baysoy G, Uslu N, et al. Fecal calprotectinconcentration is increased in children with celiac disease:relation with histopathological findings[J]. Turk J Gastroenterol,2012, 23(5): 503-508. |

| [43] | Ertekin V, Selimoglu MA, Turgut A, et al. Fecal calprotectinconcentration in celiac disease[J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2010,44(8): 544-546. |

| [44] | Waligora-Dupriet AJ, Campeotto F, Romero K, et al. Diversityof gut Bifidobacterium species is not altered between allergicand non-allergic French infants[J]. Anaerobe, 2011, 17(3): 91-96. |

| [45] | Berni Canani R, Rapacciuolo L, Romano MT, et al. Diagnosticvalue o |

2014, Vol. 16

2014, Vol. 16