喘息是小儿常见的疾病,近年来发病率有上 升的趋势,起病多见于2 岁以内的婴幼儿,以1~6 个月的婴幼儿为著[1]。引起儿童反复喘息的原因众 多[2],如:病毒感染、气道发育不良、哮喘等, 病毒感染和气道发育不良随着病因的去除、患儿 年龄的增长、气道发育完善,喘息症状可不再出 现,但哮喘患儿仍可反复发作甚至延续至成年, 对于哮喘患儿需及早干预以防气道重塑发生,但 由于幼儿肺功能检测难以实施,哮喘诊断困难, 如何有效鉴别5 岁以下儿童哮喘并予早期干预一 直成为当今热议的话题[3]。哮喘预测指数(asthma predictive index,API)是目前认为一种非常有用的 预测婴幼儿哮喘的指标[4,5]。本研究主要通过对5 岁以下喘息儿童按API 进行分组治疗,比较不同 治疗方案在疾病稳定期的疗效差异。 1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象

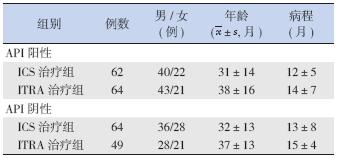

选择2011 年1 月至2012 年12 月期间在我院 住院或门诊就诊的5 岁以下喘息患儿239 例,平 均年龄35±14 个月,所有患儿的诊断均符合《儿 童哮喘的诊断治疗:PRACTALL 共识报告》的标 准[6]。根据API 严格标准分为API 阳性组与API 阴性组。API 阳性组126 人,男83 人,女43 人; 阴性组113 人,男64 人,女49 人。2 组再分别 随机分为孟鲁司特钠治疗组(LTRA 治疗组)与糖 皮质激素吸入治疗组(ICS 治疗组)。各组患儿 在年龄结构、性别组成、平均病程、疾病严重程 度、患儿一般状况等方面比较差异无统计学意义 (P>0.05)(表 1)。

| 表 1 各组患儿一般情况 |

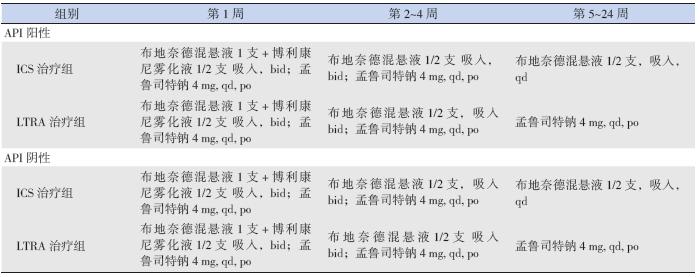

ICS 治疗组和LTRA 治疗组患儿在喘息急性发 作期(第1~4 周)采用相同常规治疗方法,包括 选择合理抗生素、布地奈德混悬液及博利康尼雾 化吸入、维持水、电解质平衡,同时辅以化痰、 退热、给氧等综合治疗,疾病稳定后(第5~24 周) 采用不同的治疗方案,见表 2。

| 表 2 各组患儿的治疗方案 |

疗效指标:记录患儿日、夜间哮喘症状评分 (表 3),将日、夜间评分相加求得合计分作为喘 息症状的评价指标。

| 表 3 哮喘日、夜间症状评分量表 |

观察时点:观察记录初诊首日(第0 天)、 治疗后第4 天、第1 周、第2 周、第4 周、第12 周、 第24 周,共7 次。 1.4 统计学分析

采用SPSS 16.0 统计软件进行统计分析,描述

性方法总结病例入组及分布、基线资料情况。计

量资料以均数± 标准差( ±s)表示,组间及治

疗前后比较分别采用两独立样本t 检验和配对t 检

验,P<0.05 为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果

2.1 不同治疗方案患儿治疗前哮喘症状评分的比较

±s)表示,组间及治

疗前后比较分别采用两独立样本t 检验和配对t 检

验,P<0.05 为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果

2.1 不同治疗方案患儿治疗前哮喘症状评分的比较

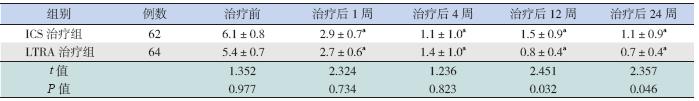

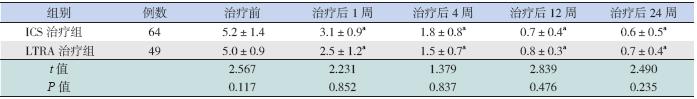

API 阳性组中,ICS 治疗组和LRTA 治疗组 哮喘症状评分比较差异无统计学意义(t=1.352, P=0.977);API 阴性组中,两个治疗组间哮喘 症状评分比较差异亦无统计学意义(t=2.567, P=0.117)(表 4~5)。

| 表 4 API 阳性患儿两个治疗组各时间点哮喘症状评分比较 |

| 表 5 API 阴性患儿两个治疗组各时间哮喘症状评分比较 |

API 阳性组中,在治疗后前4 周,两个治疗 组的哮喘症状评分均显著下降,与治疗前比较差 异有统计学意义(P<0.05),但两组间比较差异 无统计学意义;治疗后12 周和24 周时,两个治 疗组哮喘症状评分仍低于治疗前,LTRA 治疗组 较ICS 治疗组下降更显著(P<0.05)。API 阴性组 中,在治疗后前4 周,两个治疗组的哮喘症状评 分均显著下降,与治疗前比较差异有统计学意义 (P<0.05),但两治疗组间比较差异无统计学意义; 治疗后12 周和24 周时,两个治疗组哮喘症状评 分仍低于治疗前(P<0.05),但两治疗组间比较差 异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表 4~5。 2.3 不良反应

ICS 治疗的喘息患儿,有10 例出现口腔白色 念珠菌感染,予制霉菌素涂口腔及加强口腔护理 后缓解,LTRA 治疗者未发现不良反应。 3 讨论

我国2008 年《支气管哮喘的诊断和防治指南》 将5 岁以下喘息儿童分为一过性喘息、非特应性 喘息、持续哮喘、严重间歇喘息4 大类[6]。其中, 持续哮喘及严重间歇喘息儿童是支气管哮喘的高 危儿童。临床医生需要一项能预测5 岁以下儿童 喘息是否会发展为哮喘的工具,并根据预测结果 对有发展为哮喘可能的儿童进行必要的干预,以 达到预防喘息发作的目的,而API 是一项非常有 用的预测哮喘的工具[1,7]。

API 指生后3 年内反复喘息的儿童,如果符 合以下1 项主要指标或2 项次要指标,则为API 阳性[8],主要指标包括父母有哮喘史及医生诊断的 湿疹,次要指标包括医生诊断的变应性鼻炎、非 感冒性喘息或外周血中嗜酸性粒细胞≥ 4%。API 的判断有严格标准和宽松标准之分,符合1 项主 要指标或2 项次要指标,如1 年内喘息发作≥ 4 次, 为严格指标,如1 年内喘息发作<3 次,为宽松指标。 符合严格指标的喘息患儿,约76% 在学龄期发展 为哮喘,符合宽松指标的喘息患儿,约59% 在学 龄期发展为哮喘,API 特异性达97%,被不同人群 和RCT 研究采用。因此,临床将API 严格标准作 为5 岁以下儿童喘息是否发展为哮喘的预测工具。

本研究根据API 严格标准进行分组,根据不 同组别分别采用不同方案治疗,着重研究喘息患 儿稳定期的适宜治疗方案。研究结果提示,在疾 病稳定期,ICS 治疗与LTRA 口服治疗均有效,但 API 阳性组患儿对于LTRA 加雾化治疗及治疗后期 单用抗白三烯药物即LTRA 治疗更为敏感,这可能 与API 阳性组患儿后期更易发展为哮喘有关。API 阳性的喘息患儿,76% 在学龄期发展为哮喘,API 阴性喘息患儿,仅5% 在学龄期发展为哮喘[8],说 明有哮喘家族史的喘息患儿更易在学龄期发展为 哮喘。研究发现血清类粘蛋白1 样蛋白3(ORMDL3) 基因[9,10,11]、ADRB2[12]、ADAM33[13] 都与哮喘有关, 我国学者研究显示儿童哮喘易感基因单核苷酸多 态性位点FcεR1 E237G AG 杂合子在API 阳性组 频率明显高于阴性组,说明该杂合子与API 阳性 患儿喘息相关[14]。哮喘易感基因的发现,有力证 明支气管哮喘是一种遗传因素参与的疾病。

抗炎治疗是哮喘治疗的基础,全球哮喘防治 创议(GINA)推荐以ICS 为基础的治疗方案,ICS 是临床上常用的,有效治疗和预防哮喘发作的方 法。对学龄前儿童的喘息,研究表明,ICS 治疗能 有效改善喘息症状,降低肺功能损害[15,16,17]。但也 有研究指出,ICS 并不能改变学龄前儿童发展为 哮喘的进程[18,19]。抗白三烯药物在成人、青少年 及学龄儿童使用广泛[20,21,22]。包括短期使用[23]、长 期使用[24] 及与ICS 联合使用,短期使用持续1 个 月,长期使用持续3 个月以上,可抑制气道炎症, 降低气道高反应,改善肺功能。研究显示,对病 毒感染引起的喘息,使用抗白三烯药物1 年,有 效减少病毒感染所致的喘息急性发作和急救药物 的使用,延长抗白三烯药物的使用,ICS 的用量减 少39.8%[24]。对API 阳性喘息患儿,使用抗白三烯 药物能减轻喘息急性发作的严重程度[25]。LTRA 与 ICS 联合使用的研究有限,研究显示两药联用可降 低哮喘症状恶化的风险[26]。本研究显示,ICS 治疗 与LTRA 治疗同样有效,与国外研究结果一致。 两者相比,API 阳性组的LTRA 效果优于ICS,这 可能与儿童喘息的表现多样,API 标准中,父母有 哮喘病史是主要指标,也说明了遗传因素在儿童 喘息中的重要地位。

支气管哮喘是以气道炎症为主的全身性变应 性疾病,病程长且有遗传因素参与的喘息患儿, 即API 阳性患儿,同时针对气道炎症和全身性以 嗜酸性细胞参与为主的变应性炎症治疗,可能更 为有效。因此,包括了遗传因素在内的API 是一 种非常有用的预测支气管哮喘的工具,根据API 对喘息儿童进行分类,预测支气管哮喘并采取适 合的治疗方案,对于儿童喘息发作的预防及控制 有一定作用。

| [1] | Brand PL, Baraldi E, Bisgaard H, et al. Definition, assessment and treatment of wheezing disorders in preschool children: an evidence-based approach[J]. Eur Respir J, 2008, 32(4): 1096- 1110. |

| [2] | 姚苗苗, 王克明, 许群英, 等. 婴幼儿喘息的病因及相关危 险因素分析[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2011, 13(3): 195-198. |

| [3] | Camargo CA Jr. Human rhinovirus, wheezing illness, and the primary prevention of children asthma[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2013, 188(11): 1281-1282. |

| [4] | Castro-Rodriguez JA. The Asthma Predictive Index: A very useful tool for predicting asthma in young children[J]. J AllergyClin Immunol, 2010, 126(2): 212-216. |

| [5] | Guilbert TW. Identifying and managing the infant and toddler at risk for Asthma[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2010, 126(2): 417- 422. |

| [6] | 中华医学会儿科学分会呼吸学组, 《中华儿科杂志》编辑委 员会. 儿童支气管哮喘诊断与防治指南[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2008, 46(10): 745-753. |

| [7] | 王秀芳, 杨金玲, 乔俊英, 等. 5 岁以下喘息儿童鼻咽分泌物 嗜酸性粒细胞和IL-17 测定的临床意义[J]. 中国当代儿科杂 志, 2010, 12(2): 113-116. |

| [8] | Castro-Rodriguez JA, Holberg CJ, Wright AL, et al. A clinical index to define risk of asthma in young children with recurrent wheezing[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2000, 162(4 Pt 1): 1403-1406. |

| [9] | Hirota T, Harada M, Sakashita M, et al. Genetic polymorphism regulating ORM1-like3 ( Saccharomyces cerevisiae) expression is associated with childhood atopic asthma in a Japanese population[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2008, 121(3): 769-770. |

| [10] | Galanter J, Choudhry S, Eng C, et al. ORMDL3 gene is associated with asthma in three ethnically diverse populations[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2008, 177(11): 1194-1200. |

| [11] | Wu H, Romieu I, Sienra-Monge JJ, et al. Genetic variation in ORM1-like 3 (ORMDL3) and gasdermin-like (GSDML) and childhood asthma[J]. Allergy, 2009, 64(4): 629-635. |

| [12] | Pinto LA, Stein RT, Kabesch M. Impact of genetics in childhood asthma[J]. J Pediatr( Rio J), 2008, 84(4): S68-S75. |

| [13] | Lee YH, Song GG. Association between ADAM33 T1 polymorphism and susceptibility to asthma in Asians[J]. Inflamm Res, 2012, 61(12): 1355-1362. |

| [14] | 陈虹, 刘海沛, 鲍一笑, 等. 哮喘易感基因多态性与哮喘预 测指数阳性婴幼儿喘息的相关性[J]. 临床儿科杂志, 2013, 31(6): 547-550. |

| [15] | Papi A, Nicolini G, Boner AL, et al. Short term efficacy of nebulized beclomethasone in mild-to-moderate wheezing episodes in preschool children[J]. Ital J Pediatr, 2011, 37: 39. |

| [16] | Zeiger RS, Mauger D, Bacharier LB, et al. Daily or intermittent budesonide in preschool children with recurrent wheezing[J]. N Engl J Med, 2011, 365(21): 1990-2001. |

| [17] | Baraldi E, Rossi GA, Boner AL. Budesonide in preschoolage children with recurrent wheezing[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 366(6): 570-571. |

| [18] | Guilbert TW, Morgan WJ, Zeiger RS, et al. Long-term inhaled corticosteroids in preschool children at high risk for asthma[J]. N Engl J Med, 2006, 354(19): 1985-1997. |

| [19] | Murray CS, Woodcock A, Langley SJ, et al. Secondary prevention of asthma by the use of inhaled fluticasone propionate in wheezy infants (IFWIN): double-blind, randomised, controlled study[J]. Lancet, 2006, 368(9537): 754- 762. |

| [20] | GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention[EB/OL]. [February 9, 2012]. http://www. ginasthma. com. |

| [21] | British Thoracic Society, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British Guideline on the management of asthma[EB/OL]. [February 9, 2012]. http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk. |

| [22] | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma[EB/OL]. [February 9, 2012]. http://www. nhlbi. nih. gov. |

| [23] | Robertson CF, Price D, Henry R, et al. Short-course montelukast for intermittent asthma in children: a randomised controlled trial[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2007, 175(4): 323-329. |

| [24] | Bisgaard H, Zielen S, Garcia-Garcia ML, et al. Montelukast reduces asthma exacerbations in 2- to 5-yearold children with intermittent asthma[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2005, 171(4): 315-322. |

| [25] | Bacharier LB, Phillips BR, Zeiger RS, et al. Episodic use of an inhaled corticosteroid or leukotriene receptor antagonist in preschool children with moderate to severe intermittent wheezing[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2008, 122(6): 1127-1135. |

| [26] | Johnston NW, Mandhane PJ, Dai J, et al. Attenuation of the September epidemic of asthma exacerbations in children: a randomized, controlled trial of montelukast added to usual therapy[J]. Pediatrics, 2007, 120(3): e702-e712. |

2014, Vol. 16

2014, Vol. 16