2. Department of Neurosciences, University Medical Center Utrechet, Holland

孤 独 症 谱 系 障 碍(autism spectrum disorders, ASD)是发生于 3 岁以前的神经发育障碍性疾病, 以社会交流障碍、行为重复刻板和兴趣狭窄为主 要特征,发病率逐年升高,2012 年美国疾控中心 最新统计表明 ASD 的患病率为 1.4%[1]。ASD 的病 因及发病机制至今不清,遗传因素及环境因素可 能在其发病中占有重要地位 [2]。维生素 D 缺乏除 了引起钙磷代谢异常导致佝偻病和手足搐搦症外, 还具有调节免疫、抗肿瘤、抑制自身免疫等作用 [3], 并且在脑发育过程中亦发挥重要作用 [4]。新近发现 ASD 患儿存在明显的脑发育异常 [5, 6],并且推测维 生素 D 可能参与 ASD 的发病过程 [7]。目前维生素 D 缺乏是最为常见的营养缺乏性疾病之一,亦易 被人们忽视,为进一步了解 ASD 患儿维生素 D 的 营养状况,本研究对我科新诊断的 117 例 ASD 患 儿血清 25(OH)D 水平进行了检测,现报道如下。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象2013 年 9 月至 2014 年 3 月在我院小儿神经 康复门诊初次确诊的 117 例 ASD 患儿为研究组, 以在我科门诊进行常规儿童保健检查的发育正常 儿童 109 例作为对照组。所有 ASD 患儿均符合 美国精神障碍诊断统计手册第五版(DSM-V)中 ASD 的诊断标准 [8]。ASD 组患儿平均年龄 49±26 个 月,男 91 例,女 26 例; 对 照 组 男 68 例,女 41 例,平均年龄 47±24 个月。两组儿童年龄、 性别分布比较差异无统计学意义,均正常参加户 外活动,2 个月内未添加维生素 D 制剂。本研究 通过吉林大学第一医院伦理委员会批准,并已在 中国临床试验注册中心注册(注册编号:ChiCTR- CCC-14004498)。

1.2 研究方法ASD 组与对照组儿童均于晨起空腹采集静脉 血 3 mL,留取血清,采用高效液相色谱 - 串联 质谱法检测血清中 25(OH)D 的水平,浓度单位用 ng/mL 表示,本步骤由广州金域检验公司完成。根 据 25(OH)D 检测结果,患儿维生素 D 营养状况分 为正常(>30 ng/mL)、不足(10~30 ng/mL)和缺 乏(<10 ng/mL) [9]。

1.3 统计学分析应用 SPSS 17.0 统计软件进行统计学分析。对 各研究变量进行描述性分析,计数资料以绝对数 (%)表示,计量资料以均数 ± 标准差(x± s)表示。 两组间计量资料的比较采用两独立样本 t 检验;两 组间计数资料的比较采用卡方检验。 P<0.05 为差 异有统计学意义。

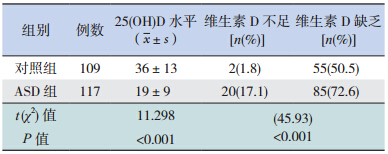

2 结果ASD 组患儿血清中 25(OH)D 水平明显低于对 照组,差异有统计学意义( P<0.001);ASD 组患 儿维生素 D 不足和缺乏率(89.7%)明显高于对照 组(52.3%),差异有统计学意义( P<0.001)。 见表 1。

| 表 1 两组儿童维生素 D 营养状况的比较 |

DSM-V 与既往的 DSM-IV 相比,对 ASD 的诊 断发生了变化,主要是去除了既往 ASD 中不同亚 型的诊断,统称为 ASD;诊断标准中将 DSM-IV 中 社会交往障碍、交流障碍、重复刻板行为和兴趣 狭窄的三分法改为社会交流障碍、重复刻板行为 和兴趣狭窄两分法,诊断条目中删除了语言发育 落后或倒退,增添了不寻常的感觉兴趣和反应, 更符合临床实际情况 [10, 11]。本研究中 117 例 ASD 患儿均符合 DSM-V 的临床诊断。

维生素 D 是人体不可或缺的营养元素,除 了外源性摄入外,更主要是通过皮肤经紫外线照 射自身合成产生,皮肤中 7- 脱氢胆固醇在紫外 线(波长 290~315 nm,紫外线指数≥ 3)经光化 学作用转变为胆骨化醇 ,即内源性维生素 D3,是 人类维生素 D 的主要来源。外源性和自身合成的 维生素 D3 在体内需经过两次羟化作用后始能发 挥生物效应:首先经肝细胞微粒体和线粒体中的 25- 羟化酶作用生成 25- 羟胆骨化醇 [25(OH)D3], 25(OH)D3 从肝脏释放入血,是维生素 D 在人体血 循环的主要形式。25(OH)D3 必须与 α- 球蛋白结 合,再转移到肾脏,经近端肾小管上皮细胞内 1α- 羟化酶作用下,再次羟化转变成 1,25- 二羟胆骨化 醇 [1,25(OH)2D3],成为活性维生素 D,发挥维生 素 D 的代谢调节作用 [12]。新近研究发现,在脑组 织、肺脏、胰腺、肠道及单核细胞、巨噬细胞、 树突状细胞等均存在 1α - 羟化酶,证明在这些部 位均可将 25(OH)D3 羟化成为活性的 1,25-(OH)2D3, 显示维生素 D 具有自分泌和旁分泌的作用 [13, 14]。 应 用 血 清 25(OH)D 作 为 检 测 体 内 维 生 素 D 水 平 的指标,主要是由于 25(OH)D 在体内稳定,半衰期 长 达 2~3 周,优 于 1,25(OH)2D3,其 半 衰 期 仅 有 4 h,且其血清水平易受甲状旁腺素水平的影 响 [15, 16]。目前常用于检测 25(OH)D 的方法有高效 液相色谱 - 串联质谱法和化学发光法。由于高效 液相色谱 - 串联质谱法较免疫化学发光法有较 突出的优点,对目标化合物的选择定性和准确定 量; 可以剔除假阳性和假阴性并且准确检测维生 素 D 总量。Farrell 等 [17] 对 170 例随机选取的患者 标本分别采用高效液相色谱 - 串联质谱法和免疫 化学发光法检测,连续 5 d 取 2 份血清 5 次重复 测量以评估批内及批外分析精度,结果高效液相 色谱 - 串联质谱法的一致相关性为 0.99,平均偏 差为 1.4 nmol/L,免疫化学发光法的一致相关性 为 0.97,平均偏差为 2.7 nmol/L。因此,本研究采 用了高效液相色谱 - 串联质谱法对研究对象进行 了 25(OH)D 的检测。目前国际上尚无统一的评定 维生素 D 营养状况的标准,本研究采用国际上较 为常用的加拿大儿科协会的标准,将血清 25(OH)D 水平 >30 ng/mL 定义为正常,10~30 ng/mL 定义为 不足,<10 ng/mL 定义为缺乏 [9]。从本研究结果来 看,ASD 患儿血清 25(OH)D 水平明显低于对照组, 且 ASD 组 患 儿 维 生 素 D 缺 乏 占 17.1%,不 足 占 72.6%,缺乏和不足患儿百分率高达 89.7%,明显 高于对照组,说明 ASD 患儿中普遍存在维生素 D 缺乏和不足。此结果与沙特阿拉伯的学者 Mostafa 等 [18] 对利雅得的 ASD 患儿的血清 25(OH)D 的研 究有相似之处,他们研究中的 ASD 患儿维生素 D 缺乏占 40%,不足占 48%,不足和缺乏患儿百分 率高达 88%。另外,本研究正常对照组中,维生 素 D 缺乏占 1.8%,维生素 D 不足占 50.5%,维生 素 D 缺乏和不足的百分率与胡有瑶等报道的沈阳 地区(北纬 41.48°)儿童维生素 D 缺乏和不足率 44.28% 近似 [19],但明显高于利雅得正常儿童 [18], 可能与长春纬度(北纬 43.88°)明显高于利雅得(北 纬 24.38°),日照时间短有关。

生命早期维生素 D 缺乏影响神经元的分化、 轴突的连接、多巴胺系统的发育以及脑的结构和 功能 [20]。母孕期维生素 D 缺乏可能通过影响胎儿 脑发育及母体免疫功能成为儿童 ASD 的危险因 素 [21];ASD 患儿在孕母服用影响维生素 D 代谢的 药物如抗癫癎药物丙戊酸中更为常见 [22];新近研 究发现,维生素 D 缺乏与包括多发性硬化、系统性红斑狼疮等自身免疫性疾病的自身抗体产生有 关 [23],而 ASD 患儿体内已证实存在抗髓磷脂相关 糖蛋白自身抗体等,这些现象亦支持维生素 D 缺 乏可能是 ASD 发病的环境因素之一。同时,已有 研究表明,精神性疾病患者中维生素 D 代谢相关 的细胞色素氧化酶 P450,特别是 CYP27B1 和维生 素 D 受体存在着基因多态性及结构变异 [24],从而 影响体内维生素 D 的代谢 ,而它们在 ASD 的作用 有待于进一步研究。

总之,本研究证实 ASD 患儿普遍存在维生 素 D 缺乏和不足,维生素 D 系统既可能作为诱发 ASD 的环境因素,亦可能作为 ASD 发生的遗传因 素。本研究存在的不足之处在于样本量较小,且 未对两组儿童间日照时间进行详细比较。因此, 进一步扩大样本量,进行科学设计对影响维生素 D 代谢的各种因素严格控制,深入研究维生素 D 在 ASD 发病机制中的作用,有可能为寻求治疗新途 径—补充维生素 D 治疗 ASD 提供理论依据。

| [1] | Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders-Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, United States, 2008[J]. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 2012, 61(SS03): 1-19. |

| [2] | Kubota T, Takae H, Miyake K. Epigenetic mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives for neurodevelopmental disorders[J]. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2012, 5(4): 369-383. |

| [3] | Autier P, Boniol M, Pizot C, et al. Vitamin D status and ill health: a systematic review[J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2014, 2(1): 76-89. |

| [4] | Salami M, Talaei SA, Davari S, et al. Hippocampal long term potentiation in rats under different regimens of vitamin D: an in vivo study[J]. Neurosci Lett, 2012, 509(1): 56-59. |

| [5] | Stoner R, Chow ML, Boyle MP, et al. Patches of disorganization in the neocortex of children with autism[J]. N Engl J Med, 2014, 370(13): 1209-1219. |

| [6] | Zielinski BA, Prigge MB, Nielsen JA, et al. Longitudinal changes in cortical thickness in autism and typical development[J]. Brain, 2014, 137(Pt 6): 1799-17812. |

| [7] | Cannell JJ, Grant WB. What is the role of vitamin D in autism?[J]. Dermatoendocrinol, 2013, 5(1): 199-204. |

| [8] | Kim YS, Fombonne E, Koh YJ, et al. A comparison of DSM-IV pervasive developmental disorder and DSM-5 autism spectrum disorder prevalence in an epidemiologic sample[J]. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2014, 53(5): 500-508. |

| [9] | Gallo S, Jean-Philippe S, Rodd C, et al. Vitamin D supplementation of Canadian infants: practices of Montreal mothers[J]. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab, 2010, 35(3): 303-309. |

| [10] | Guthrie W, Swineford LB, Wetherby AM, et al. Comparison of DSM-IV and DSM-5 factor structure models for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder[J]. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2013, 52(8): 797-805. |

| [11] | Tsai LY, Ghaziuddin M. DSM-5 ASD moves forward into the past[J]. J Autism Dev Disord, 2014, 44(2): 321-330. |

| [12] | Morris HA. Vitamin D activities for health outcomes[J]. Ann Lab Med, 2014, 34(3): 181-186. |

| [13] | Gröber U, Spitz J, Reichrath J, et al. Vitamin D: Update 2013: From rickets prophylaxis to general preventive healthcare[J]. Dermatoendocrinol, 2013, 5(3): 331-347. |

| [14] | Pludowski P, Holick MF, Pilz S, et al. Vitamin D effects on musculoskeletal health, immunity, autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, cancer, fertility, pregnancy, dementia and mortality— a review of recent evidence[J]. Autoimmun Rev, 2013,12(10): 976-989. |

| [15] | Tsagari A, Toulis KA, Makras P, et al. Performance of the mini nutritional assessment score in the detection of vitamin D status in an elderly Greek population[J]. Horm Metab Res, 2012, 44(12): 896-899. |

| [16] | Grant WB, Tangpricha V. Vitamin D: Its role in disease prevention[J]. Dermatoendocrinol, 2012, 4(2): 81-83. |

| [17] | Farrell CJ, Martin S, McWhinney B, et al. State-of-the-art vitamin D assays: a comparison of automated immunoassays with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry methods[J]. Clin Chem, 2012, 58(3): 531-542. |

| [18] | Mostafa GA, Al-Ayadhi LY. Reduced serum concentrations of 25-hydroxy vitamin D in children with autism: relation to autoimmunity[J]. J Neuroinflammation, 2012, 9: 201. |

| [19] | 胡有瑶, 张宁. 0-14 岁儿童25-羟维生素D 水平及其与季 节关系[J]. 临床儿科杂志,2014, 32(2): 194. |

| [20] | 段小燕, 贾飞勇, 姜慧轶. 维生素D 与孤独症谱系障碍的关 系[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2013, 15(8): 698-702. |

| [21] | Whitehouse AJ, Holt BJ, Serralha M, et al. Maternal vitamin D levels and the autism phenotype among offspring[J]. J Autism Dev Disord, 2013,43(7): 1495-1504. |

| [22] | Meador KJ, Loring DW. Risks of in utero exposure to valproate[J]. JAMA, 2013, 309(16): 1730-1731. |

| [23] | Marques CD, Dantas AT, Fragoso TS, et al. The importance of vitamin D levels in autoimmune diseases[J]. Rev Bras Reumatol, 2010, 50(1): 67-80. |

| [24] | Jiang P, Zhu MQ, Li HD, et al. Effects of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms on the risk of schizophrenia and metabolic changes caused by risperidone treatment[J]. Psychiatry Res, 2014, 215(3): 806-807. |

2015, Vol. 17

2015, Vol. 17