智力低下(intellectual disability,ID) 在亚洲 人群的发病率大约为0.25%~1.3%[1-2]。ID 和生长发 育迟缓(developmental delay,DD)问题越来越受 到社会关注,已成为一个非常重要的公共健康问 题。导致ID/DD 的病因复杂,遗传异常是其重要 因素,但潜在的不明原因的ID/DD 仍然很多,大 约占30%~60%[3-4]。G 显带染色体核型分析作为首 选技术已广泛用于染色体异常的检测,但该方法 对于5 Mb 以下的染色体异常无法识别,而多重链 接探针扩增技术(multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification,MLPA) 能检出5%~10% 不明原因 ID/DD 患儿存在亚端粒区域基因拷贝数变异 (CNVs)[5],不适合检测未知的点突变及染色体 平衡易位,临床进一步治疗及受累家庭再生育风 险防范仍然困难重重。微阵列比较基因组杂交技 术(array-based comparative genomic hybridization, array-CGH)突破了传统细胞遗传学方法的许多限 制,已广泛应用于检测不明原因的非综合征性的 ID/DD[6],相比较传统的染色体核型分析,array- CGH 能检测到<5 Mb 的遗传变异[7]。本研究共收 集不明原因的ID/DD 患儿16 例,采用array-CGH 技术进行全基因组扫描,以评估不明原因ID/DD 病例的遗传病因,为进一步诊治及遗传咨询提供 科学依据。 1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象

研究对象为2012 年8 月至2014 年1 月来我 院儿童遗传咨询门诊或健康门诊就诊的不明原因 ID/DD 患儿16 例,根据ID/DD 诊断及筛查标准[8], 除外有明确病因的疾病,如明确的染色体核型异 常、遗传代谢性疾病、甲状腺功能异常、颅内肿瘤、 中枢神经系统感染、围产期异常导致的缺氧缺血 性脑病、已知遗传性综合征和遗传病等。所有患 儿均为临床病例,家属同意参与研究并签署知情 同意书,并获得医院伦理委员会批准。16 例患儿 均为汉族,平均年龄6 岁(范围2 个月至16 岁), 其中男孩11 例,女孩5 例。 1.2 样本采集及预处理

在受试者安静状态下采集乙二胺四乙酸 (EDTA) 抗凝外周血2 mL,离心柱法提取基因组DNA,DNA 总量在50 μL 以上,浓度为 100~150 ng/μL,-20 ℃冰箱保存备用。 1.3 array-CGH 检测

取患儿基因组DNA 2 μg 与参考DNA 2 μg , 用Alu I 和Rsa I 在37℃条件下联合消化2 h,进行 DNA 纯化。患儿基因组DNA 使用欧联红色荧光素 cy5-dCTP 标记,参照样本DNA 使用欧联绿色荧光 素cy3-dCTP 标记,标记后DNA 用MicroCon YM-30 进行样本纯化。将上述已纯化标记患儿DNA 与 参照DNA 等量混合,加入50 μg Cot-IDNA,再用 95% 乙醇沉淀,然后使用杂交液(50% 甲酰胺、 10% 硫酸葡聚糖、4% SDS、2*SSC、10 μg/μL 酵母 tRNA)溶解DNA 沉淀,最后将已溶解的DNA 置 于70℃变性10 min 等待杂交。上样到Oligo244K 芯片上65℃杂交炉孵育40 h,杂交后使用洗涤缓 冲液清洗芯片。使用Genepix 4200A 扫描仪扫描 微阵列芯片并获取杂交信号,采用Agilent Feature Extraction 9.1 进行数据提取至DNA Analytics 3.4 软 件进行统计分析,并依据统计结果设定DNA 拷贝 数变化的判断标准。以上操作步骤可按相应试剂 盒说明书进行(Agilent 公司)。 1.4 MLPA 检测

应用MLPA P064、P096 亚端粒区检测试剂盒 (MRC-Holland)验证array-CGH 检出的2 例综合 征病例,探针杂交、连接反应及探针扩增均参照 试剂盒说明进行,扩增产物经Beckman 遗传分析 仪(CEQ8000)进行毛细管电泳分离,GeneMarker v1.6 软件分析收集到的数据,得出MLPA 图谱。 2 结果 2.1 临床表现

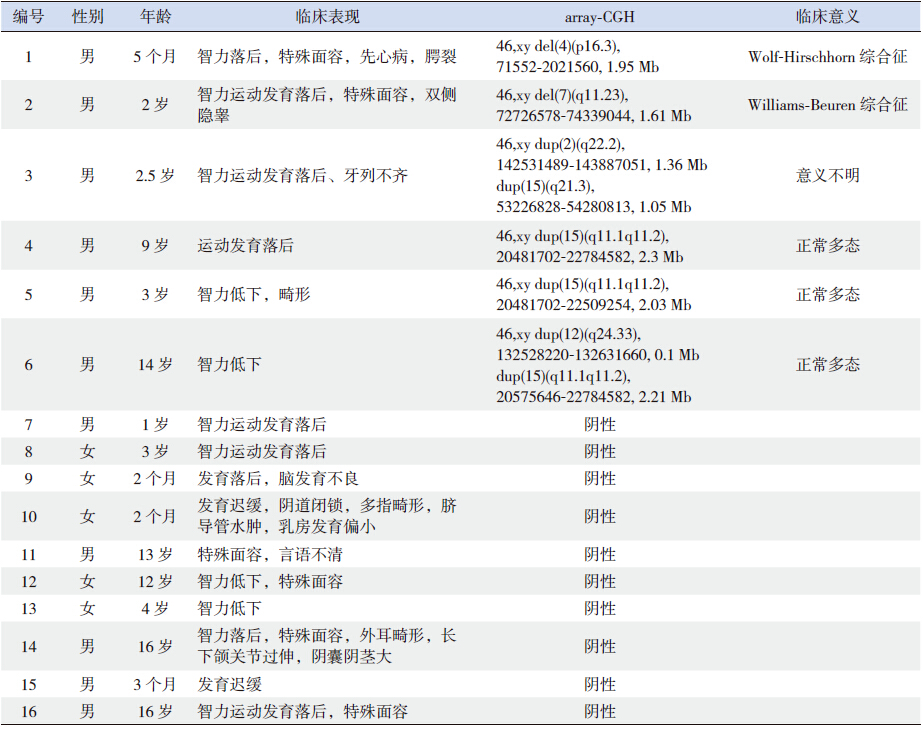

16 例患儿中,6 例(38%)患儿有不同的异 常的面部特征(高前额、宽眼距、低鼻梁、厚嘴唇、 小下颌等);6 例(38%)伴有其他畸形,包括先 天性心脏病、多指或趾畸形、阴道闭锁、隐睾等。 所有患儿均完成了常规染色体G 显带检查,均未 见明显异常。16 例患儿临床表现见表 1。

| 表 1 16 例ID/DD 患儿临床资料及array-CGH 结果 |

6 例(38%) 患儿存在CNVs。经比对 DECIPHER 数据库和既往MR/DD 或ID/DD 相 关array-CGH 研究报告,2 例明确病因,其中1例CNVs 涉及4p16.3 区域微缺失,考虑为Wolf- Hirschhorn 综合征,另1 例CNVs 涉及7q11.23 区 域微缺失,考虑为Williams-Beuren 综合征。3 例 CNVs 为正常多态性改变。1 例CNVs 临床意义不 明确,包含2 个重复突变,患儿父母经array-CGH 检测均未发现相同CNVs 改变,考虑为新生突变。 经文献查询及表型- 基因型分析,该突变包含 ARHGAP、GTDC1、KYNU、LRP1B、WDR72 等基因, 与智力低下、脑发育迟缓、特殊面容(高眉弓、 低耳位、上睑下垂等)、隐睾、牙列不齐等有关, 证实该CNVs 具有临床意义。该区域所包含的基 因及相关临床表现见表 2(https://decipher.sanger. ac.uk/)。因此,array-CGH 技术为19%(3/16)的 患儿明确了病因诊断(表 1)。

| 表 2 2 个新生突变区域所包含的基因及相关临床表现 |

正常人的MLPA 分析图谱的扩增点范围在 (0.7~1.3)之间,小于0.7 表明拷贝数缺失,大于1.3 表明拷贝数扩增,对array-CGH 检出的2 例综合征 阳性病例经过验证,结果与之符合。 3 讨论

染色体CNVs 在神经性发育障碍,如ID、 DD、孤独症、精神分裂症以及其他疑难症等发 病机制中起重要作用[9]。有报道,在因较小染色 体不平衡畸变而引起的ID、器官畸形和DD 的群 体中,常规G 显带核型分析技术的检出率约为 15%~40%[10]。array-CGH 技术突破了传统细胞遗传 学方法的许多限制,通过对人类全基因组扫描, 可检测染色体非整倍数变异、CNVs 和染色体不 平衡异位,相比较传统的染色体核型分析,array- CGH 具有高通量、高分辨率等优点,可检出染色 体的亚显微缺失和重复突变[11-13]。国外文献报道, 在针对ID、多发性先天性畸形等患者的产后遗传 诊断中,array-CGH 的检出率为7%~11%[14, 15],可 检测出92% 以上常规细胞遗传技术可检测到的基 因失衡,以及8% 的常规技术和原位杂交技术未能 检测到的基因失衡[15]。本研究利用array-CGH 技 术对不明原因ID/DD 患儿行全基因组扫描,发现 6/16 例(38%)患儿存在CNVs 异常,为19%(3/16) 的患儿明确了病因诊断。

Wolf-Hirschhorn 综合征又称4 号染色体短臂 末端亚端粒缺失综合征,约70% 的患者为新发缺 失,仅10%~15% 的患者父母为染色体平衡异位携 带者[16, 17]。Wolf-Hirschhorn 综合征相对较罕见,发 生率为1/50 000,50%~100% 的患儿伴有癫癎,典 型的面部特征为希腊头盔样面容,宫内或出生后 生长发育迟缓、肌张力低下、骨骼畸形、先天性 心脏病、听力丧失、泌尿及胃肠道畸形等也较常 见[18, 19]。例1 为5 个月男婴,以智力落后、特殊面容、 先天性心脏病、腭裂为主诉就诊,经array-CGH 分 析,发现染色体4p16.3 有一约1.95 Mb 缺失,该 区域的缺失是目前唯一明确的Wolf-Hirschhorn 综 合征致病基因,因此该患儿Wolf-Hirschhorn 综合 征诊断明确。

Williams-Beuren 综合征是因7 号染色体长臂 近着丝粒端片段7q11.23 微缺失引起,以认知缺陷、 轻度精神发育不良和主动脉狭窄为主要特点,还 可有特殊面容(宽前额、低鼻梁、星状蓝色巩膜、 长人中、大嘴、下唇突出、尖下巴、牙齿稀小, 又称“精灵脸”)、高钙血症、继发性高血压等 表现,发病率为1/20 000~1/7 500[20]。ELN(弹性蛋白基因)缺失可导致主动脉发育不良,进而引起 主动脉瓣上狭窄,是Williams-Beuren 综合征的特 征性改变;GTF2I 基因与认知能力、分离焦虑有关; GTF2IRD1 与视动整合能力有关; 而GTF2IRD1/ GTF2I 基因簇参与面部异形化改变。Williams- Beuren 综合征早期生理表现轻微、不明显,缺乏 典型的临床表现,初次诊断从16 个月到12 岁不 等,平均5 岁,由于他们多动、多话及过分友好 的性格很容易被人忽略他们的智力问题[21]。例2 为2 岁男性幼儿,因智力运动发育落后、特殊面 容、双侧隐睾就诊,染色体核型分析无异常,经 array-CGH 分析,发现染色体7q11.23 存在一大小 约1.61 Mb 微缺失,该区域存在多个致病基因,如 CLIP2、ELN、LIMK1、FKBP6、GTF2IRD1/GTF2I 基因簇和EIF4H 等基因,均与Williams-Beuren 综 合征有关,经完善血生化、心脏超声、眼底、视 力等相关检查,发现该患儿还存在主动脉狭窄、 高钙血症,因此患儿诊断Williams-Beuren 综合征 明确,但体查并未发现患儿心脏各瓣膜区明显病 理性杂音,且临床无紫绀等表现,需定期复查心 脏超声及血钙、血压等指标评估病情变化,及时 手术,延长存活时间。

Mulatinho 等[22] 报道,在染色体2q22.1q22.3 区域存在8 个基因,包括:HNMT、SPOPL、 NXPH2、LOC64702、LRP1B、KYNU、ARHGAP15 和 GTDC1,并证实该部位的缺失与智力低下、先 天性畸形和孤独症等疾病有关。本研究通过比对 DECIPHER 数据库发现染色体2q22.2 重复区域主 要包括LRP1B、KYNU、ARHGAP15 和 GTDC1 共 4 个基因,Lynn 等[23] 报道,LRP 1B 是儿童肥胖遗 传易感基因之一,Timms 等[24] 通过array-CGH、连 锁分析、外显子测序等方法对3 个精神分裂症家 系检测发现,LRP1B 基因系罹患精神分裂症风险 相关的新基因。而染色体15q21.3 重复区域的主要 功能基因WDR72 与胼胝体、牙釉质等发育不良有 关。本研究中例3 患儿就诊时2.5 岁,表现为智力 运动发育落后、牙列不齐,array-CGH 检测发现染 色体存在2 个不同部位的重复突变,其包含的多 个基因均与其临床表现相符,故为致病突变,具 有临床意义,且为新生突变。该患儿年龄尚小, 将来有发生孤独症或精神分裂症等相关疾病的风 险,需要随访观察。

在不明原因ID/DD 中,利用array-CGH 技术 能检出致病性CNVs 约15%~20%,该技术目前已 作为一线诊断方法用于不明原因ID/DD 和(或) 先天性畸形的检测[25-26]。本研究中致病CNVs 检出 率为19%,与G 显带染色体核型分析相比,优缺 点各异,这就要求临床医生根据受检者具体情况 选择合适的检测手段,以达到利益最大化目的[27]。

| [1] | Jeevanandam L. Perspectives of intellectual disability in Asia: epidemiology, policy, and services for children and adults[J]. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 2009, 22(5): 462-468. |

| [2] | Kwok HW, Chui EM. A survey on mental health care for adults with intellectual disabilities in Asia[J]. J Intellect Disabil Res, 2008, 52(11): 996-1002. |

| [3] | Croen LA, Grether JK, Selvin S. The epidemiology of mental retardation of unknown cause[J]. Pediatrics, 2001, 107(6): E86. |

| [4] | Rauch A, Hoyer J, Guth S, et al. Diagnostic yield of various genetic approaches in patients with unexplained developmental delay or mental retardation[J]. Am J Med Genet A, 2006, 140(19): 2063-2074. |

| [5] | Novelli A, Ceccarini C, Bernardini L, et al. High frequency of subtelomeric rearrangements in a cohort of 92 patients with severe mental retardation and dysmorphism[J]. Clin Genet, 2004, 66(1): 30-38. |

| [6] | Shaffer LG, Bejjani BA. Medical applications of array CGH and the transformation of clinical cytogenetics[J]. Cytogenet Genome Res, 2006, 115(3-4): 303-309. |

| [7] | Oostlander AE, Meijer GA, Ylstra B. Microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization and its applications in human genetics[J]. Clin Genet, 2004, 66(6): 488-495. |

| [8] | American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders[M].Washington, DC: Alllerican Psychiatric Association, 2000. |

| [9] | Lee C, Iafrate AJ, Brothman AR. Copy number variations and clinical cytogenetic diagnosis of constitutional disorders[J]. Nat Genet, 2007, 39(7 Suppl): S48-54. |

| [10] | Hulten MA, Dhanjal S, Pertl B. Rapid and simple prenatal diagnosis of common chromosome disorders: advantages and disadvantages of the molecular methods FISH and QF-PCR[J]. Reproduction, 2003, 126(3): 279-297. |

| [11] | Shaffer LG, Bejjani BA, Torchia B, et al. The identification of microdeletion syndromes and other chromosome abnormalities: cytogenetic methods of the past,new technologies for the future[J]. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet, 2007, 145C(4): 335-345. |

| [12] | Dale RC, Grattan-Smith P, Nicholson M, et al. Microdeletions detected using chromosome microarray in children with suspected genetic movement disorders: a single-centre study[J]. Dev Med Child Neurol, 2012, 54(7): 618-623. |

| [13] | Kurian MA. The clinical utility of chromosomal microarray in childhood neurological disorders[J]. Dev Med Child Neurol, 2012, 54(7): 582-583. |

| [14] | Pickering DL, Eudy JD, Olney AH, et al. Array-based comparative genomic hybridization analysis of 1176 consecutive clinical genetics investigations[J]. Genet Med, 2008, 10(4): 262-266. |

| [15] | Park SJ, Jung EH, Ryu RS, et al. Clinical implementation of whole-genome array CGH as a first-tier test in 5080 pre and postnatal cases[J]. Mol Cytogenet, 2011, 9(4): 12. |

| [16] | Hart L, Rauch A, Carr AM, et al. LETM1 haploinsufficiency causes mitochondrial defects in cells from humans with Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome: implications for dissecting the underlying pathomechanisms in this condition[J]. Dis Model Mech, 2014, 7(5): 535-545. |

| [17] | Cyr AB, Nimmakayalu M, Lonmuir SQ, et al. A novel 4p16.3 microduplication distal to WHSC1 and WHSC2 characterized by oligonucleotide array with new phenotypic features[J]. Am J Med Genet A, 2011, 155A(9): 2224-2228. |

| [18] | Hannelie E, Jasper JS, Ruben S, et al. Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome facial dysmorphic features in a patient with a terminal 4p16.3 deletion telomeric to the WHSCR and WHSCR 2 regions[J]. Eur J Hum Genet, 2009, 17(1): 129-132. |

| [19] | Hammond P, Hannes F, Suttie M, et al. Fine-grained facial phenotype-genotype analysis in Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome[J]. Eur J Hum Genet, 2012, 20(1): 33-40. |

| [20] | Martens MA, Wilson SJ, Reutens DC. Research review: Williams syndrome: a critical review of the cognitive, behavioral, and neuroanatomical phenotype[J]. J Child Psychol Psych, 2008, 49(6): 576-608. |

| [21] | Lisa E, Aaron P, Sherly P, et al. An atypical deletion of the Williams-Beuren syndrome interval implicates genes associated with defective visuospatial processing and autism[J]. J Med Genet, 2007, 44(2): 136-143. |

| [22] | Mulatinho MV, de Carvalho Serao CL, Scalco F, et al. Severe intellectual disability, omphalocele, hypospadia and high blood pressure associated to a deletion at 2q22.1q22.3: case report[J]. Mol Cytogenet, 2012, 5(1): 30. |

| [23] | Lynn M, Shah N, Conroy J, et al. A study of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma copy number alterations by single nucleotide polymorphism analysis[J]. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol, 2014, 22(3): 213-221. |

| [24] | Timms AE, Dorschner MO, Wechsler J, et al. Support for the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor hypofunction hypothesis of schizophrenia from exome sequencing in multiplex families[J]. JAMA Psychiatry, 2013, 70(6): 582-590. |

| [25] | Ahn JW, Mann K, Walsh S, et al. Validation and implementation of array comparative genomic hybridisation as a first line test in place of postnatal karyotyping for genome imbalance[J]. Mol Cytogenet, 2010, 15(3): 9. |

| [26] | Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, et al. Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 2010, 86(5): 749-764. |

| [27] | Shoukier M, Klein N, Auber B, et al. Array CGH in patients with developmental delay or intellectual disability: are there phenotypic clues to pathogenic copy number variants?[J]. Clin Genet, 2013, 83(1): 53-65. |

2015, Vol. 17

2015, Vol. 17