上世纪初德国的Albert Niemann 和Ludwig Pick 描述了一组常染色体隐性遗传的溶酶体脂 质贮积病,表现为组织细胞内酸性鞘磷脂沉积、 肝脾肿大,伴或不伴有神经系统受累,把这样一 组疾病命名为尼曼匹克病(Niemann-Pick disease, NPD)。上世纪50 年代,Crocker 和Farber 观察到 NPD 在发病年龄和临床表现方面差异很大,又结 合其分子生物学特征,把NPD 分为A、B、C 和D 四型。随着分子生物学技术的发展和诊断水平的 进步,目前已知A 型和B 型均是由于SMPD1 基因 突变导致其编码的酸性鞘磷脂酶(ASM)活性下 降或缺失,引起溶酶体内酸性鞘磷脂沉积,所以 又合称为酸性鞘磷脂酶缺陷病。NPD C 型(NPC) 和D 型是由于NPC1 或NPC2 基因突变所致,主要 病理改变是组织细胞内大量游离胆固醇沉积。NPC 病变常累及神经系统和内脏器官,临床表现有明显的异质性,易被误诊、漏诊,近年来对NPC 的 认识有了明显进展,国内报告的病例也逐渐增多, 该文将从NPC 的临床表现、发病机制和诊断、治 疗方面作一综述,旨在加强临床医生对该病的认 识。 1 临床表现

NPC 病人常有肝、脾、肺、骨髓等内脏器官 和广泛的神经系统受累,因发病年龄不同,病变 累及范围不一致,临床表现有很大的异质性,一 般发病年龄越早,病情越重,严重的在新生儿期 发病,短期内即可引起死亡,成人发病可以表现 为慢性神经系统变性病[1]。典型病例常首先表现为 全身受累,如新生儿期出现的胆汁淤积性黄疸, 婴儿期或儿童期出现的肝脾肿大或单纯的脾脏肿 大,然后影响到神经系统,出现小脑、脑干、基 底节和大脑皮层等部位受累的症状[1, 2],神经系统 表现主要包括:快速眼动异常、共济失调、辨距 不良、构音障碍、吞咽困难和进行性痴呆,痴笑 猝倒发作、癫癎发作、听力损害和肌张力障碍也 比较常见,最具特征性的表现是垂直性核上性眼 肌麻痹(vertical supranuclear gaze palsy,VGSP)[1, 2, 3, 4], 痴笑猝倒发作是因突然的肌张力丧失,不能维持 立位姿势而跌倒,不伴有意识障碍,也是NPC 特 异性症状之一[3, 4, 5]。

临床常根据神经系统受累情况进行分类或区 分疾病的严重程度,神经系统症状出现越早,病 情越重,进展越快,预后也越差。按神经系统症 状出现的年龄,NPC 又分为:(1)新生儿型(起 病年龄<2 个月):常表现为腹水、胆汁淤积性 黄疸和肝脾肿大;严重的肝功能损害使患儿多在 6 个月内死亡,本型可不表现出神经系统症状。 (2)早期婴幼儿型(起病年龄2 个月至<2 岁): 肝脾肿大常见;从8~9 个月开始出现肌张力低 下,继而出现运动功能丧失、痉挛和震颤;多数 患儿在5 岁前死亡。(3)晚期婴幼儿型(起病年 龄2~6 岁):起病前智力运动发育基本正常,逐 渐出现轻微的宽基底步态,进而出现明显的共济 失调、肌张力不全、精神发育倒退;1~2 年后出现 VGSP,如伴有严重癫癎则意味着预后不良,常在 7~12 岁死亡;(4)青少年型(起病年龄6~15 岁)VGSP 是最典型的体征之一;其他症状包括动作笨 拙、学习障碍、猝倒发作、共济失调和行走困难, 半数患儿伴有癫癎,晚期构音障碍和吞咽困难恶 化,大多在20 岁前死亡;(5)青春期和成人型(起 病年龄>15 岁):隐匿起病,精神症状早于运动 和认知症状出现,包括妄想、幻听或幻视等[1, 2, 3, 4]。

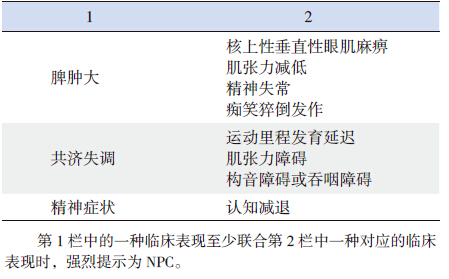

除神经系统表现外,其他系统受累症状主要 是脾脏肿大或肝脾肿大,肝功能损害,脾功能亢 进引起的血小板减少、贫血等;还可以出现间质 性肺病和反复呼吸道感染,可能与肺部巨噬细胞 吞噬功能降低,泡沫细胞沉积有关,但严重的肺 部病变少见[1]。典型NPC 病人常有内脏器官、神 经系统和精神方面联合受累的表现(表 1)。

| 表 1 NPC 特异的临床表现组合 |

NPC 是一种常染色体隐性遗传的溶酶体脂质 贮积病,根据致病基因不同又分为NPC1 和NPC2 两个亚型,其中NPC1 占95%,NPC2 目前仅报 道30 余例,两者在病理变化及临床表现方面无明 显区别[1]。D 型也是由于NPC1 基因突变所致,这 类病人主要见于加拿大Nova Scotia 省阿卡迪亚人 的后裔,目前已归类于NPC1[1, 6]。NPC1 基因位于 18q11.2,全长56 kb,编码区包含25 个外显子, 编码1 种大分子跨膜蛋白,该蛋白位于晚期胞内 体和溶酶体膜上,含13 个跨膜结构域,其中位于 胞内的类固醇感应区和富含半胱氨酸的指环结构 为其重要的功能区[7]。NPC2 基因位于14q24.3, 全长13.5 kb,编码区包含5 个外显子,编码1 种 小分子的可溶性蛋白,位于晚期胞内体和溶酶体 的基质内,这两种蛋白对胆固醇有很强的亲和力,主要功能是在溶酶体和晚期胞内体中转运胆 固醇和其他酯类,共同调控胆固醇的外流,维持 胆固醇和其他酯类在细胞内的动态稳定,但具体 作用机制还不是很清楚[8, 9, 10]。至今已发现300 余 种NPC1 和NPC2 基因序列变异(http://www.hgmd. cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php),基因突变类型和临床表型 有一定的相关性[1],发生在类固醇感应区的错义、 无义或移码突变,对NPC1 蛋白的功能有更大的影 响,趋于出现严重的临床表型[11],但NPC 同胞发 病也可以出现不同的临床表现[12],说明临床表型 尚受其他机制的调控。近些年国内报道的NPC 病 人逐渐增多,中国人发生的NPC 突变类型[13, 14, 15] 与 欧洲研究的突变热点(p.I1061T)[16] 不一致。

正常情况下低密度脂蛋白(LDL)通过泡饮作 用进入细胞内,在晚期胞内体和溶酶体中被溶酶体 酸性脂肪酶水解而释放出游离胆固醇,再经NPC2 和NPC1 蛋白的交替转运,到其他细胞器或细胞膜 上被利用[10, 17, 18],这两种蛋白的功能下降或缺失会 引起细胞对游离胆固醇的处理和利用障碍,是NPC 发病的始动环节[9, 17, 18]。在非神经组织中游离胆固 醇的沉积可继发性引起神经鞘磷脂、鞘糖脂和鞘 氨醇等的沉积[19],而在神经元细胞内引起的继发 性改变主要为神经节苷脂的沉积(GM2、GM3), 这些脂类成分的沉积共同参与了NPC 发病的病理 生理过程[19, 20]。近来的研究表明,细胞内脂质成 分的失衡会影响自噬溶酶体的形成,从而影响细 胞对受损细胞器和有凝聚倾向蛋白的自我清理功 能[21, 22, 23],细胞的这种自噬功能是维持细胞内环境 稳定的重要因素,自噬功能缺陷是发生肝损害和 神经变性的主要原因之一[21, 23, 24, 25]。脂分解代谢和细 胞自噬功能是相互关联的,两者受同一种机制调 控[21],脂分解代谢障碍,胆固醇外流受阻会影响 细胞的自噬功能,自噬功能缺陷又会加重脂类在 细胞内的沉积,形成恶性循环,是NPC 发病的关 键环节[26, 27, 28]。动物实验中NPC1 突变大鼠的溶酶体 和胞内体中鞘氨醇沉积影响细胞膜结构的完整性 和膜上离子通道的功能,引起细胞内钙离子浓度 的下降,细胞内钙稳态失衡会引起胆固醇、鞘磷 脂和鞘糖脂等的流出障碍,所以钙稳态的失衡在 NPC 的发病过程中起重要作用[29]。还有证据显示 脂质沉积后导致的线粒体功能障碍和抗氧化酶活 性下降等将引发一系列细胞内的氧化应激反应,这种异常的氧化应激反应在NPC 病人肝细胞损伤 和神经元凋亡的病理生理过程中起重要作用[30]。 由于以上的病理生理变化,中枢神经系统内脂类 成分大量沉积,结果影响了神经元树突的形成和 导致神经元凋亡,数量逐渐减少,这种影响最先 出现在小脑的浦肯野细胞,逐渐进展而累及基底 神经节、海马细胞和大脑锥体细胞等[31, 32]。最近 动物实验表明大鼠的小脑浦肯野细胞和胶质细胞 NPC1 缺失后,突触前膜的自发电位活动和兴奋性 信号的输入性传导受到明显影响[33],病理结果提 示NPC1-/- 大鼠神经元的变性从神经末梢开始,进 而逆行累及到神经元胞体[34, 35]。成年大鼠在敲除 NPC1 基因后将发生神经变性[36],发生神经变性后 的NPC1-/- 大鼠,再转入NPC1 基因能够阻止神经 变性的继续进展[37, 38],以上实验结果提示NPC1 缺 失是神经变性的独立影响因素。 3 实验室检查

皮肤成纤维细胞培养Filinpin 染色发现异常的 游离胆固醇沉积或行NPC 基因检查发现致病性突 变可以明确诊断NPC[1, 3, 4, 39],基因检查也可用于产 前诊断[3, 4, 13]。

骨髓涂片或脾穿刺活检找到尼曼匹克细胞(泡 沫细胞)和/ 或海蓝组织细胞为NPD 的组织学特 征之一,可以作为快速筛查的方法,但不是所有 NPC 病人均可找到[40],骨髓涂片发现泡沫细胞也 不能作为确诊NPC 的依据[41],一般来讲NPC 病人 出现了典型的泡沫细胞,说明疾病已经对病人造 成了严重的影响,大都伴有巨脾、血小板减少、 骨髓浸润和明显的神经系统症状[3, 4]。血生化检查 可以有LDL、高密度脂蛋白(HDL)降低和甘油 三酯升高,尤以HDL 降低更常见,并与NPC 的严 重程度呈负相关[41],其他常见的异常指标还有外 周血白细胞减少、贫血和血小板降低,肝功能损 害和肌酶升高等也较常见,但均为非特异性改变。

头颅核磁共振或头颅CT 检查,在晚期病人可 以见到不同程度的脑萎缩表现。腹部超声检查可 以发现不同程度的脾肿大或肝脾肿大。

近来的研究发现NPC 病人血清中羟固醇(胆 固醇的氧化产物)明显升高,今后有可能作为筛 查NPC 病人的特异性标记物[42, 43]。 4 诊断与鉴别诊断

NPC 诊断需全面详细的了解病史,细致的 体格检查,特别注意神经系统的特异性表现,如 VSGP、共济失调、构音障碍和吞咽困难等。NPC 临床表现复杂多变,因发病年龄和就诊时间不同, 每个具体病人的表现可以有很大差异,当病人出 现表 1 中的某一组症状时,需高度怀疑为NPC[3]。

VSGP 是NPC 特征性表现之一,如再合并脾 肿大或共济失调要高度怀疑本病,痴笑猝倒发作 是NPC 另一个特异性表现,虽较VSGP 少见, 但若合并有脾肿大等其他表现时,也强烈提示为 NPC[3, 4, 39]。新生儿期出现难以解释的并持续存在的 胆汁淤积性黄疸时应考虑到NPC,婴幼儿出现发 育迟滞是非特异性症状,如果运动里程发育落后、精细动作不协调,合并脾脏肿大或快速眼动异常, 是早期诊断NPC 的指征[3, 4],但是没有脾脏肿大也 不能除外NPC[4]。

确诊NPC 仍需在培养的成纤维细胞中发现异 常沉积的游离胆固醇或NPC(NPC1 或NPC2)基 因检查发现致病性突变。

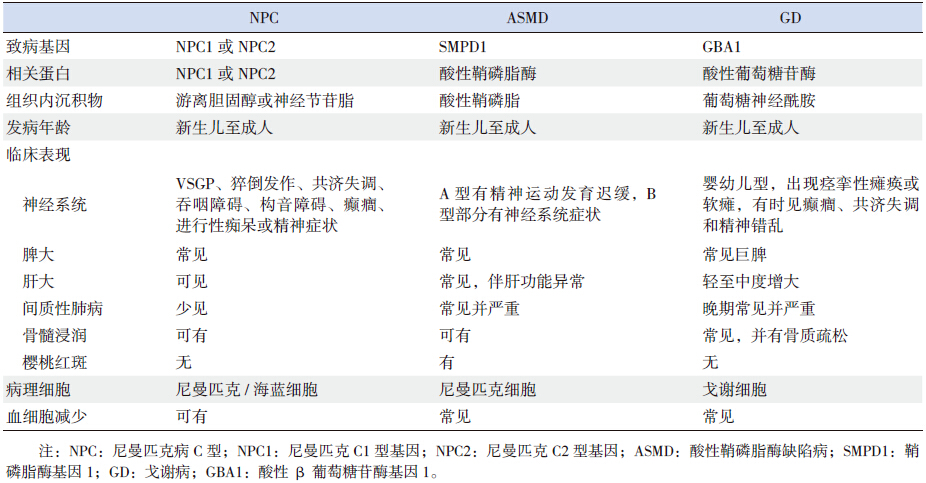

NPC的鉴别诊断主要是酸性鞘磷脂酶缺陷病、 戈谢病等其他脂质沉积性疾病(表 2)、先天性新 生儿肝炎和其他原因引起的新生儿胆汁淤积性黄 疸,较大的儿童还要与其他原因引起的小脑性共 济失调、肌张力障碍、猝倒、核上性眼肌麻痹相 鉴别。青少年与成人发病多表现为精神症状和认 知损害,要与阿尔兹海默病、额颞痴呆和精神分 裂症区别。

| 表 2 NPC 与酸性鞘磷脂酶缺陷病和戈谢病的鉴别诊断 |

NPC 目前尚无有效的治疗方法,以对症治疗 为主,采用综合治疗方法,改善病人的神经功能 和生存质量。

美格鲁特是目前唯一在欧洲、澳大利亚和日 本等国家批准用于治疗NPC 的特效药物,经长 期随访观察和队列研究证实,美格鲁特可以稳定 并改善NPC 病人的神经系统症状,延长预期寿 命[44, 45, 46, 47],为避免神经系统损害继续加重,NPC 病 人应在确诊后尽早给予美格鲁特治疗[2]。该药主要 的不良反应为胃肠不适、腹泻和体重下降,坚持 用药一段时间后可逐渐减轻[48, 49]。

抗氧化剂维生素E 在动物实验中能延缓NPC 大鼠浦肯野细胞的丢失和神经变性的发生[50],临 床上已用于NPC 病人的治疗。

吞咽障碍是NPC 病人致死的原因之一[51],对 出现吞咽困难的病人,应给予粘稠的流质饮食或通过胃造瘘术摄入食物,避免发生吸入性肺炎并 保证充足的营养供应。

其他对症治疗方法还有:应用三环类抗抑郁 药物改善NPC 病人的痴笑猝倒发作,抗胆碱药物 减轻病人的肌张力障碍和肢体不自主抖动。

随着对NPC 发病机制的深入研究,又不断 开发出新的药物,目前研究较多的药物为羟丙 基-β- 环糊精,在动物实验中可部分替代NPC1 和NPC2 的功能[52],并通过调节乙酰辅酶A 酰基 转移酶活性促进胆固醇酯化,减少游离胆固醇的 沉积[53],可以改善神经系统症状及肝脏损害[54], 但具体作用机制还不清楚,尚未应用于临床。

其他治疗方法还包括:脾切除适用于非神经 型NPC 有脾功能亢进者;异基因造血干细胞移植 治疗NPC 已有成功的报道[55, 56];转基因疗法目前 尚处于动物实验阶段[1, 2]。

| [1] | Vanier MT. Niemann-Pick disease type C[J]. J Orphanet J Rare Dis, 2010, 5: 16. |

| [2] | Patterson MC, Hendriksz CJ, Walterfang M, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Niemann-Pick disease type C: an update[J]. Mol Genet Metab, 2012, 106(3): 330-344. |

| [3] | Mengel E, Klunemann HH, Lourenco CM, et al. Niemann-Pick disease type C symptomatology: an expert-based clinical description[J]. Orphanet J Rare Dis, 2013, 8: 166. |

| [4] | Wijburg FA, Sedel F, Pineda M, et al. Development of a suspicion index to aid diagnosis of Niemann-Pick disease type C[J]. Neurology, 2012, 78(20): 1560-1567. |

| [5] | Oyama K, Takahashi T, Shoji Y, et al. Niemann-Pick disease type C: cataplexy and hypocretin in cerebrospinal fluid[J]. Tohoku J Exp Med, 2006, 209(3): 263-267. |

| [6] | Greer WL, Riddell DC, Byers DM, et al. Linkage of Niemann-Pick disease type D to the same region of human chromosome 18 as Niemann-Pick disease type C[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 1997, 61(1): 139-142. |

| [7] | Millat G, Marçais C, Tomasetto C, et al. Niemann-Pick C1 disease: correlations between NPC1 mutations, levels of NPC1 protein, and phenotypes emphasize the functional significance of the putative sterol-sensing domain and of the cysteine-rich luminal loop[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 2001, 68(6): 1373-1385. |

| [8] | Storch J, Xu Z. Niemann-Pick C2 (NPC2) and intracellular cholesterol trafficking[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2009, 1791(7): 671-678. |

| [9] | Abi-Mosleh L, Infante RE, Radhakrishnan A, et al. Cyclodextrin overcomes deficient lysosome-to-endoplasmic reticulum transport of cholesterol in Niemann-Pick type C cells[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009, 106(46): 19316-19321. |

| [10] | Dixit SS, Jadot M, Sohar I, et al. Loss of Niemann-Pick C1 or C2 protein results in similar biochemical changes suggesting that these proteins function in a common lysosomal pathway[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(8): e23677. |

| [11] | Millat G, Marçais C, Tomasetto C, et al. Niemann-Pick C1 disease: correlations between NPC1 mutations, levels of NPC1 protein, and phenotypes emphasize the functional significance of the putative sterol-sensing domain and of the cysteine-rich luminal loop[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 2001, 68(6): 1373-1385. |

| [12] | Vanier MT, Wenger DA, Comly ME, et al. Niemann-Pick disease group C: clinical variability and diagnosis based on defective cholesterol esterification. A collaborative study on 70 patients[J]. Clin Genet, 1988, 33(5): 331-348. |

| [13] | 章瑞南, 邱文娟, 叶军, 等. 尼曼-匹克病C型一家系基因突变分析及产前基因诊断[J]. 中华围产医学杂志, 2013, 16(12): 750-755. |

| [14] | Xiong H, Higaki K, Wei CJ, et al. Genotype/phenotype of 6 Chinese cases with Niemann-Pick disease type C[J]. Gene, 2012, 498(2): 332-335. |

| [15] | Yang CC, Su YN, Chiou PC, et al. Six novel NPC1 mutations in Chinese patients with Niemann-Pick disease type C[J]. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2005, 76(4): 592-595. |

| [16] | Millat G, Marçais C, Rafi MA, et al. Niemann-Pick C1 disease: the I1061T substitution is a frequent mutant allele in patients of Western European descent and correlates with a classic juvenile phenotype[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 1999, 65(5): 1321-1329. |

| [17] | Mesmin B, Maxfield FR. Intracellular sterol dynamics[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2009, 1791(7): 636-645. |

| [18] | Rosenbaum AI, Maxfield FR. Niemann-Pick type C disease: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic approaches[J]. J Neurochem, 2011, 116(5): 789-795. |

| [19] | Zervas M, Dobrenis K, Walkley SU. Neurons in Niemann-Pick disease type C accumulate gangliosides as well as unesterified cholesterol and undergo dendritic and axonal alterations[J]. Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2001, 60(1): 49-64. |

| [20] | te Vruchte D, Lloyd-Evans E, Veldman RJ, et al. Accumulation of glycosphingolipids in Niemann-Pick C disease disrupts endosomal transport[J]. Biol Chem, 2004, 279(25): 26167-26175. |

| [21] | Singh R, Cuervo AM. Lipophagy: connecting autophagy and lipid metabolism[J]. Int J Cell Biol, 2012, 2012: 282041. |

| [22] | Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, et al. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology[J]. Physiol Rev, 2010, 90(4): 1383-1435. |

| [23] | Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, et al. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion[J]. Nature, 2008, 451(7182): 1069-1075. |

| [24] | Komatsu M. Liver autophagy: physiology and pathology[J]. J Biochem, 2012, 152(1): 5-15. |

| [25] | Sarkar S. Regulation of autophagy by mTOR-dependent and mTOR-independent pathways: autophagy dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases and therapeutic application of autophagy enhancers[J]. Biochem Soc Trans, 2013, 41(5): 1103-1130. |

| [26] | Peake KB, Vance JE. Normalization of cholesterol homeostasis by 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin in neurons and glia from Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1)-deficient mice[J]. J Biol Chem, 2012, 287(12): 9290-9298. |

| [27] | Meske V, Erz J, Priesnitz T, et al. The autophagic defect in Niemann-Pick disease type C neurons differs from somatic cells and reduces neuronal viability[J]. J Neurobiol Dis, 2014, 64: 88-97. |

| [28] | Sarkar S, Carroll B, Buganim Y, et al. Impaired autophagy in the lipid-storage disorder Niemann-Pick type C1 disease[J]. Cell Rep, 2013, 5(5): 1302-1315. |

| [29] | Lloyd-Evans E, Morgan AJ, He X, et al. Niemann-Pick disease type C1 is a sphingosine storage disease that causes deregulation of lysosomal calcium[J]. Nat Med, 2008, 14(11): 1247-1255. |

| [30] | Vázquez MC, Balboa E, Alvarez AR, et al. Oxidative stress: a pathogenic mechanism for Niemann-Pick type C disease[J]. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2012, 2012: 205713. |

| [31] | Walkley SU, Suzuki K. Consequences of NPC1 and NPC2 loss of function in mammalian neurons[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2004, 1685(1-3): 48-62. |

| [32] | Elrick MJ, Pacheco CD, Yu T, et al. Conditional Niemann-Pick C mice demonstrate cell autonomous Purkinje cell neurodegeneration[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2010, 19(5): 837-847. |

| [33] | Buard I, Pfrieger FW. Relevance of neuronal and glial NPC1 for synaptic input to cerebellar Purkinje cells[J]. Mol Cell Neurosci, 2014, 61: 65-71. |

| [34] | Sarna JR, Larouche M, Marzban H, et al. Patterned Purkinje cell degeneration in mouse models of Niemann-Pick type C disease[J]. J Comp Neurol, 2003, 456(3): 279-291. |

| [35] | Macauley SL, Sidman RL, Schuchman EH, et al. Neuropathology of the acid sphingomyelinase knockout mouse model of Niemann-Pick A disease including structure-function studies associated with cerebellar Purkinje cell degeneration[J]. Exp Neurol, 2008, 214(2): 181-192. |

| [36] | Yu T, Shakkottai VG, Chung C, et al. Temporal and cell-specific deletion establishes that neuronal Npc1 deficiency is sufficient to mediate neurodegeneration[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2011, 20(22): 4440-4451. |

| [37] | Lopez ME, Klein AD, Dimbil UJ, et al. Anatomically defined neuron-based rescue of neurodegenerative Niemann-Pick type C disorder[J]. Neurosci, 2011, 31(12): 4367-4378. |

| [38] | Erickson RP. Current controversies in Niemann-Pick C1 disease: steroids or gangliosides; neurons or neurons and glia[J]. Appl Genet, 2013, 54(2): 215-224. |

| [39] | Wraith JE, Sedel F, Pineda M, et al. Niemann-Pick type C Suspicion Index tool: analyses by age and association of manifestations[J]. Inherit Metab Dis, 2014, 37(1): 93-101. |

| [40] | Rodrigues AF, Gray RG, Preece MA, et al. The usefulness of bone marrow aspiration in the diagnosis of Niemann-Pick disease type C in infantile liver disease[J]. Arch Dis Child, 2006, 91(10): 841-844. |

| [41] | Patterson MC, Hendriksz CJ, Walterfang M, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Niemann-Pick disease type C: an update[J]. Mol Genet Metab, 2012, 106(3): 330-344. |

| [42] | Porter FD, Scherrer DE, Lanier MH, et al. Cholesterol oxidation products are sensitive and specific blood-based biomarkers for Niemann-Pick C1 disease[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2010, 2(56): 56ra81. |

| [43] | Jiang X, Sidhu R, Porter FD, et al. A sensitive and specific LC-MS/MS method for rapid diagnosis of Niemann-Pick C1 disease from human plasma[J]. Lipid Res, 2011, 52(7): 1435-1445. |

| [44] | Patterson MC, Vecchio D, Jacklin E, et al. Long-term miglustat therapy in children with Niemann-Pick disease type C[J]. J Child Neurol, 2010, 25(3): 300-305. |

| [45] | Wraith JE, Vecchio D, Jacklin E, et al. Miglustat in adult and juvenile patients with Niemann-Pick disease type C: long-term data from a clinical trial[J]. Mol Genet Metab, 2010, 99(4): 351-357. |

| [46] | Patterson MC, Vecchio D, Prady H, et al. Miglustat for treatment of Niemann-Pick C disease: a randomised controlled study[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2007, 6(9): 765-772. |

| [47] | Pineda M, Wraith JE, Mengel E, et al. Miglustat in patients with Niemann-Pick disease Type C (NP-C): a multicenter observational retrospective cohort study[J]. Mol Genet Metab, 2009, 98(3): 243-249. |

| [48] | Belmatoug N, Burlina A, Giraldo P, et al. Gastrointestinal disturbances and their management in miglustat treated patients[J]. Inherit Metab Dis, 2011, 34(5): 991-1001. |

| [49] | Champion H, Ramaswami U, Imrie J, et al. Dietary modifications in patients receiving miglustat[J]. Inherit Metab Dis, 2010, 33 Suppl 3: S379-S383. |

| [50] | Marín T, Contreras P, Castro JF, et al. Vitamin E dietary supplementation improves neurological symptoms and decreases c-Abl/p73 activation in Niemann-Pick C mice[J]. Nutrients, 2014, 6(8): 3000-3017. |

| [51] | Walterfang M, Chien YH, Imrie J, et al. Dysphagia as a risk factor for mortality in Niemann-Pick disease type C: systematic literature review and evidence from studies with miglustat[J]. Orphanet J Rare Dis, 2012, 7: 76. |

| [52] | Rosenbaum AI, Cosner CC, Mariani CJ, et al. Thiadiazole carbamates: potent inhibitors of lysosomal acid lipase and potential Niemann-Pick type C disease therapeutics[J]. Med Chem, 2010, 53(14): 5281-5289. |

| [53] | Abi-Mosleh L, Infante RE, Radhakrishnan A, et al. Cyclodextrin overcomes deficient lysosome-to-endoplasmic reticulum transport of cholesterol in Niemann-Pick type C cells[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009, 106(46): 19316-19321. |

| [54] | Liu B, Ramirez CM, Miller AM, et al. Cyclodextrin overcomes the transport defect in nearly every organ of NPC1 mice leading to excretion of sequestered cholesterol as bile acid[J]. Lipid Res, 2010, 51(5): 933-944. |

| [55] | 潘静, 耿哲, 江华, 等. 异基因造血干细胞移植治疗儿童尼曼匹克病1例报告[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2013, 15(9): 782-784. |

| [56] | Bonney DK, O'Meara A, Shabani A, et al. Successful allogeneic bone marrow transplant for Niemann-Pick disease type C2 is likely to be associated with a severe 'graft versus substrate' effect[J]. Inherit Metab Dis, 2010, 33 Suppl 3: S171-S173. |

2015, Vol. 17

2015, Vol. 17