2. 浙江省立同德医院儿科, 浙江 杭州 310012

近年来儿童肥胖发病率的增加遍及全球,与此同时女童青春期启动时间显著提前[1, 2],证据显示肥胖是促进女童性腺启动的主要原因之一[3, 4]。最近研究表明青春期肥胖女童促黄体生成素(LH)分泌脉冲频率及峰值均较正常体重者降低[5, 6]。Lee等[7] 研究发现性早熟男童LH激发峰值与体重指数(BMI)呈负相关,本团队前期研究发现BMI与性早熟女童LH激发峰值呈负相关[8],然而另一项单中心性早熟女童的研究显示高BMI值与阴毛、腋毛早现及骨龄提前相关,但与LH峰值、LH/卵泡刺激素(FSH)比值无关[9]。尽管肥胖对LH激发峰值的影响及其机制研究尚未阐明,但肥胖对青春期启动时间及激素水平的影响是明确的,并可导致肥胖相关并发症。过度肥胖及相关激素可能对下丘脑促性腺激素释放激素(GnRH)的分泌产生影响。

本研究通过分析不同BMI指数性早熟女童的性激素对GnRH激发试验的反应来研究肥胖对性早熟女童LH激发峰值的影响,在前期研究基础上,进一步探讨肥胖相关激素及神经激肽等影响性早熟女童LH激发峰值的作用机制,为临床精确分析和综合判断GnRH试验以及性早熟的诊断提出新的建议。 1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象及分组

采用随机分层抽样方法,选取2012~2014年于本院确诊为中枢性性早熟,且年龄在6~9岁间的333例女童为研究对象(小于6岁的性早熟女童 因缺乏相应的BMI 标准未被纳入研究,月经来潮 者亦未纳入本项研究)。其中正常体重组123例(BMI:5% ~),超重组108例(BMI:85% ~),肥胖组102例(BMI ≥ 95%)。所有研究对象均无器质性疾病,并且未服用对性腺轴有影响的药物。儿童中枢性性早熟诊断标准参照卫生部2010 年颁布的《性早熟诊疗指南(试行)》[10]:男童 在9岁前,女童在8 岁前呈现第二性征或女童在 10 周岁前出现月经。儿童超重、肥胖判断标准参 照中国2~18岁儿童肥胖、超重筛查BMI界值点标准[11]:根据身高、体重计算BMI(BMI=体重/身高2),BMI在P85~范围内者为超重,BMI ≥ P95者为肥胖,且平素体健(无内分泌及遗传代谢疾病引发的继发性肥胖),近期无降血糖、降脂及有肝损作用的药物服用史,无酒精饮用史。本研究经所有患儿家长知情同意,并获得医院伦理委员会批准。 1.2 体格指标检测

受检者脱鞋帽、穿单衣,由专人使用标准方法测量其体重、身高,分别精确到0.1 kg、0.1 cm。 标准差单位(SDS)=(测量值- 平均数)/ 标准差 (SD)。 1.3 第二性征评价

由经统一培训的儿科内分泌医生进行,包括女 性乳房、阴毛。乳房发育评价采用视诊和触诊法,阴毛发育评价采用视诊法,按Tanner 分期标准,乳 房发育分为B1~B5期,阴毛发育分为PH1~PH5期[12],两侧乳房发育分期不同,则记录发育较成熟的一侧。 1.4 实验室及辅助检查

333例患者基础血清样本在GnRH(商品名: 戈那瑞林,生产厂家:马鞍山丰原制药有限公司,批号:H10960064) 注射前采集,GnRH(2.5~ 3 μg/kg,最大100 μg)注射后30、45、60、90 min采集血清标本检测LH、FSH 峰值。血清LH、 FSH、雌激素(E2)水平通过美国西门子公司化 学发光免疫分析仪检测。每组各随机抽取20 例 患儿进一步检测血清瘦素(leptin)、神经激肽B (neurokiniB)、吻素(kisspeptin) 和性激素结 合蛋白(SHBG)水平。leptin 采用放射免疫法检 测(leptin试剂盒,北京北方生物科技公司),neurokiniB 和kisspeptin 通过酶联免疫吸附试验(ELISA)检测(neurokiniB及kisspeptin试剂盒,美国凤凰制药公司),SHBG通过电化学发光法检测(SHBG诊断试剂盒,德国罗氏诊断有限公司)。

骨龄通过拍摄左手正位X线片(包括腕骨及桡尺骨下端),统一由本院专科医师按GP图谱法测算骨龄[13]。卵巢及子宫容积通过超声检查计算(0.523× 长× 宽× 深度),下丘脑- 垂体MRI 检查排除颅内占位病变。 1.5 统计学分析

采用SPSS 17.0统计学软件对数据进行统计学分析,正态分布的计量资料以均数±标准差(x±s)表示,多组间比较采用方差分析,组间两两比较采用SNK-q 检验;非正态分布的计量资料以中位数(范围)表示,多组间比较采用Kruskal Wallis H检验,组间两两比较采用Wilcoxon秩和检验。计数资料采用百分率(%)表示,多组间等级资料 比较采用Kruskal Wallis H 检验。对BMI与血清激素水平及骨龄的相关性分析采用Person相关分析。P<0.05 为差异有统计学意义。 2 结果 2.1 临床特征分析

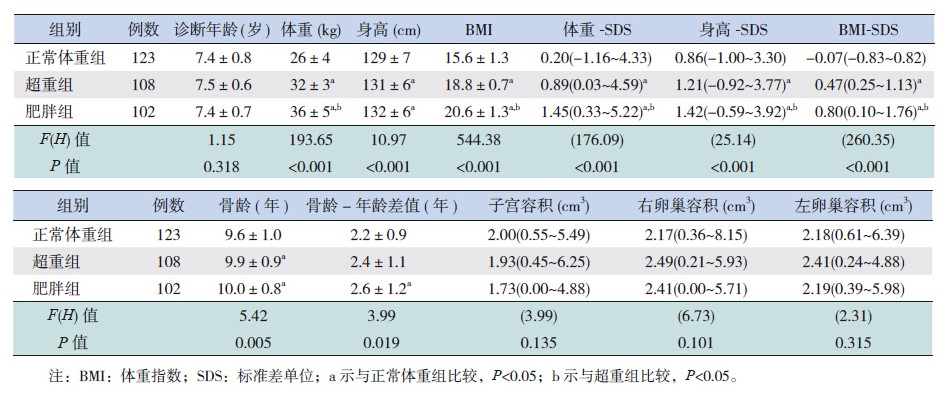

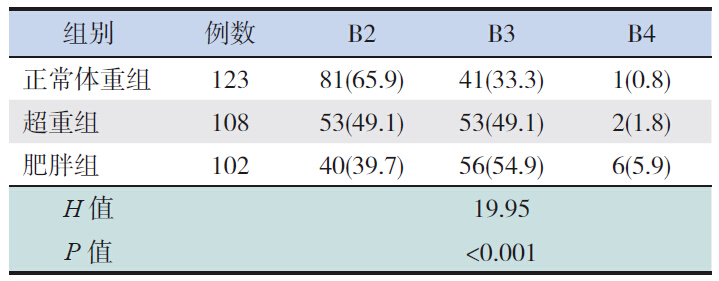

各组患儿平均诊断年龄差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);肥胖组体重-SDS、身高-SDS和BMISDS显著高于超重组及正常体重组(P<0.05)。 超重组及肥胖组的骨龄显著大于正常体重组(P<0.05);子宫、卵巢容积在3组间比较差异无统计学意义(表 1)。各组性早熟女童乳房发育Tanner分期比例分布差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),正常体重组以B2期为主,见表 2。

| 表 1 333例性早熟女童一般临床资料比较[x±s或中位数(范围)] |

| 表 2 各组乳房发育Tanner分期[例(%)] |

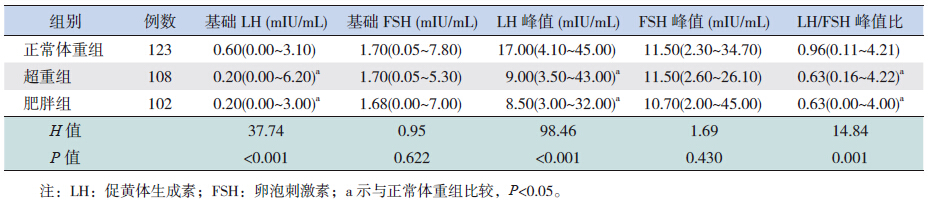

正常体重组基础LH、LH激发峰值以及LH/FSH比值明显高于肥胖组及超重组(P<0.05),但在超重组和肥胖组间比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。三组间基础FSH和FSH峰值比较差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表 3。

| 表 3 333例性早熟女童血清激素水平比较[中位数(范围)] |

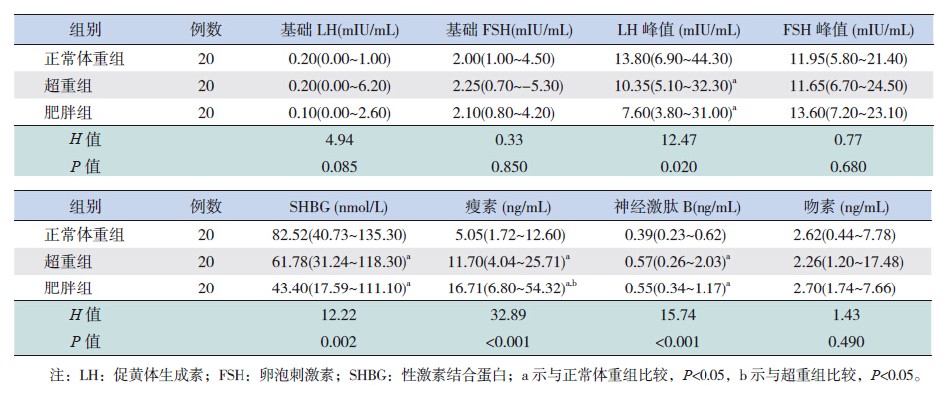

正常体重组LH激发峰值和血清SHBG水平显著高于超重组及肥胖组(P<0.05);血清leptin及neurokiniB水平显著低于超重及肥胖组,其中超 重组leptin水平低于肥胖组(P<0.05)。各组间血 清基础LH、基础FSH、FSH峰值及kisspeptin水平差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表 4。

| 表 4 60例性早熟女童血清激素水平比较[ 中位数(范围)] |

结果显示性早熟女童的BMI与LH激发峰值、基础LH值和SHBG水平呈负相关(分别r=-0.429、-0.314、-0.555,P<0.01);与leptin水平和骨龄呈正相关(分别r=0.692、0.203 P<0.01)。 3 讨论

肥胖对女性激素水平的影响贯穿青春前期、青春期及成年期。近期研究表明青春前期及青春期肥胖女童睡眠相关LH分泌减弱[5, 6, 14],肥胖妇女 平均LH水平、LH脉冲分泌振幅、LH激发峰值也显著低于正常体重者[15],肥胖患者月经周期中孕酮、LH、FSH水平相对较低[16]。本研究数据显示 正常体重者血清基础LH及LH激发峰值较超重及肥胖组显著升高,与前期研究结论一致。这些数据提示过度肥胖在一定程度上反而抑制了下丘脑- 垂体-性腺轴的功能。然而,另外一项研究则显示肥胖与阴毛、腋毛早现及骨龄进展有关,但对LH分泌无明显影响[9],这可能与该实验将年龄低 于3 岁的性早熟女童也纳入了研究有关,不能除 外“小青春期”的干扰。因此还需多中心大样本的临床试验进一步明确肥胖对青春期LH分泌的影 响及作用机制。

肥胖对下丘脑-垂体-性腺轴的作用机制目前尚未明确。本研究发现肥胖伴性早熟女童血清leptin和neurokiniB水平显著高于正常组,而血清SHBG水平则低于正常组。Leptin由外周成熟脂肪细胞分泌,通过外周及中枢受体参与能量平衡和生殖内分泌的调节[17]。人类leptin及其受体突变可导致不同程度的低促性腺素性功能减退症、食欲增加及肥胖[18]。在青春期早期,血清leptin水平存在性别差异,女童血清leptin水平明显高于男童,这与女童性早熟发病率高于男童一致[19]。人类及动物实验研究均显示,外源性leptin与下丘脑leptin受体结合后可增加GnRH脉冲分泌频率,刺激LH及FSH分泌[20, 21],高水平leptin可促进青春期启动[22]。然而研究显示血清leptin水平与肥胖呈正相关,这可能与leptin抵抗有关[23]。因此,尽管肥胖儿童外周leptin水平增加,由于存在中枢抵抗,中枢leptin水平不足以刺激GnRH分泌,从而抑制LH分泌[24]。

最新研究显示肥胖相关的内分泌机制与青春前期血清SHBG下降密切相关,女童5岁时SHBG水平越低,进入TannerⅡ期越早,LH分泌、生长加速、月经来潮越早[25]。一项肥胖高加索儿童的研究显示,减肥后男童胰岛素敏感性、血清SHBG、FSH、LH水平均显著升高,女童血清LH水平无明显改变[26]。身体脂肪分布的遗传危险性(genetic risk score,GRS)与血清SHBG水平下降显著相关,并且GRS与SHBG对胰岛素抵抗具有叠加效应[27]。青春期生长激素及IGF-1分泌增加,降低了胰岛素敏感性,从而出现代偿性高胰岛素血症,这种代偿性高胰岛素血症在肥胖女童中表现更为明显[28]。高胰岛素血症不仅降低了SHBG的合成、雌激素的灭活[25, 29],也增加了芳香化酶的活性,使血清睾酮向雌激素转换加速,从而促进乳房发育[28]。然而,长期高水平的雌激素可降低下丘脑-垂体-性腺轴的敏感性及负反馈抑制作用,最终导致LH激发峰值降低。

NeurokiniB(NKB)是影响青春期启动的另一因素,通过与下丘脑的受体结合参与生殖内分泌的调节。编码NKB及其受体NK3R的基因失活突变可导致低促性腺素性功能减退症和不孕症[30]。动物实验显示NKB/NK3R通路在雌鼠青春前期及成年期适当激素环境下可控制LH释放[31, 32]。Kinsey-Jones等[33]发现NKB激动剂可抑制卵巢切除后雌激素替代治疗的雌鼠LH分泌,另一项研究显示NKB受体拮抗剂可减少LH分泌的频率和振幅,并使雌鼠青春期启动延迟[34]。本研究显示肥胖及超重性早熟女童血清NKB水平较正常体重组高,但LH激发峰值则低于正常体重组,与动物实验研究结论相符。

Kisspeptin及其受体是调节GnRH分泌的重要信号通路。人类遗传研究显示编码Kisspeptin的基因KISS1失活突变可导致低促性腺素性功能减退症[35],编码其受体的基因GPR54激活突变可导致中枢性性早熟[36]。动物模型显示Kiss-1在性早熟雌鼠下丘脑mRNA表达较正常对照显著增加[37]。肥胖青春前期女童血清kisspeptin水平较正常对照高[38],在leptin缺乏的动物模型中,kisspeptin表达减少[39, 40],然而给leptin缺乏的啮齿动物外源性注射kisspeptin可增加促性腺激素的分泌[39]。这些研究表明kisspeptin神经核可能是leptin的下游调控因子,共同参与性腺轴的调控。大量研究表明NKB为Kisspeptin神经核的上游调控因子,共同参与生殖内分泌的调控[31, 41, 42]。本研究显示正常体重组血清kisspeptin水平较肥胖组低,与动物实验研究结论一致,但差异不具有统计学意义,可能与样本量小有关。leptin,neurokiniB和kisspeptin之间的相互作用及对下丘脑-垂体-性腺轴的调控机制需更进一步研究证实。

本研究显示肥胖伴中枢性性早熟女童LH激发峰值相对较低,可能与血清高leptin、neurokiniB和低SHBG水平及其信号通路的调节作用相关。在对肥胖伴中枢性性早熟女童的诊断过程中需要考虑BMI的影响因素,同时还需更多实验研究脂肪因子、神经激肽及其信号通路对GnRH分泌的调控机制。

| [1] | Euling SY, Herman-Giddens ME, Lee PA, et al. Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings[J]. Pediatrics, 2008, 121(3): S172-S191. |

| [2] | Soriano-Guillen L, Corripio R, Labarta JI, et al. Central precocious puberty in children living in Spain: incidence, prevalence, and influence of adoption and immigration[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2010, 95(9): 4305-4313. |

| [3] | Lee JM, Appugliese D, Kaciroti N, et al. Weight status in young girls and the onset of puberty[J]. Pediatrics, 2007, 119(3): e624-e630. |

| [4] | Dai YL, Fu JF, Liang L, et al. Association between obesity and sexual maturation in Chinese children: a muticenter study[J]. Int J Obes (Lond), 2014, 38(10): 1312-1316. |

| [5] | Bordini B, Littlejohn E, Rosenfield RL. Blunted sleep-related luteinizing hormone rise in healthy premenarcheal pubertal girls with elevated body mass index[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2009, 94(4): 1168-1175. |

| [6] | Collins JS, Beller JP, Burt Solorzano C, et al. Blunted day-night changes in luteinizing hormone pulse frequency in girls with obesity: the potential role of hyperandrogenemia[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2014, 99(8): 2887-2896. |

| [7] | Lee HS, Park HK, Ko JH, et al. Impact of body mass index on luteinizing hormone secretion in gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation tests of boys experiencing precocious puberty[J]. Neuroendocrinology, 2012, 97(3): 225-231. |

| [8] | Fu JF, Liang JF, Zhou XL, et al. Impact of BMI on gonadorelin-stimulated LH peak in premenarcheal girls with idiopathic central precocious puberty[J]. Obesity (Silver Spring), 2015, 23(3): 637-643. |

| [9] | Giabicani E, Allali S, Durand A, et al. Presentation of 493 consecutive girls with idiopathic central precocious puberty: a single-center study[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(7): e70931. |

| [10] | 中华人民共和国卫生部. 性早熟诊疗指南(试行)[卫办医政发(195)号][J]. 中国儿童保健杂志, 2011, 19(4): 390-392. |

| [11] | 李辉, 季成叶, 宗心南, 等. 中国0-18岁儿童、青少年体块指数的生长曲线[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2009, 47(7): 487-492. |

| [12] | Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls[J]. Arch Dis Child, 1969, 44(235): 291-303. |

| [13] | Greulich WPS. Radiographic atlas of skeletal development of the hand and wrist[M]. 2nd edition. California: Stanford University Press, 1959: 145-150. |

| [14] | Rosenfield RL, Bordini B. Evidence that obesity and androgens have independent and opposing effects on gonadotropin production from puberty to maturity[J]. Brain Res, 2010, 1364: 186-197. |

| [15] | Roth LW, Bradshaw-Pierce EL, Allshouse AA, et al. Evidence of GnRH antagonist escape in obese women[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2014, 99(5): E871-E875. |

| [16] | Yeung EH, Zhang C, Albert PS, et al. Adiposity and sex hormones across the menstrual cycle: the BioCycle Study[J]. Int J Obes (Lond), 2013, 37(2): 237-243. |

| [17] | Chan JL, Matarese G, Shetty GK, et al. Differential regulation of metabolic, neuroendocrine, and immune function by leptin in humans[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2006, 103(22): 8481-8486. |

| [18] | Farooqi IS, Wangensteen T, Collins S, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic spectrum of congenital deficiency of the leptin receptor[J]. N Engl J Med, 2007, 356(3): 237-247. |

| [19] | Martos-Moreno GA, Barrios V, Argente J. Normative data for adiponectin, resistin, interleukin 6, and leptin/receptor ratio in a healthy Spanish pediatric population: relationship with sex steroids[J]. Eur J Endocrinol, 2006, 155(3): 429-434. |

| [20] | Martos-Moreno GA, Chowen JA, Argente J. Metabolic signals in human puberty: effects of over and undernutrition[J]. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2010, 324(1-2): 70-81. |

| [21] | Soliman AT, Yasin M, Kassem A. Leptin in pediatrics: a hormone from adipocyte that wheels several functions in children[J]. Indian J Endocrinol Metab, 2012, 16(3): S577-S587. |

| [22] | Franco JG, Lisboa PC, da Silva Lima N, et al. Resveratrol prevents hyperleptinemia and central leptin resistance in adult rats programmed by early weaning[J]. Horm Metab Res, 2014, 46(10): 728-735. |

| [23] | Shimizu H, Oh IS, Okada S, et al. Leptin resistance and obesity[J]. Endocr J, 2007, 54(1): 17-26. |

| [24] | Pan H, Guo J, Su Z. Advances in understanding the interrelations between leptin resistance and obesity[J]. Physiol Behav, 2014, 130: 157-169. |

| [25] | Pinkney J, Streeter A, Hosking J, et al. Adiposity, chronic inflammation, and the prepubertal decline of sex hormone binding globulin in children: evidence for associations with the timing of puberty (earlybird 58)[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2014, 99(9): 3224-3232. |

| [26] | Birkebaek NH, Lange A, Holland-Fischer P, et al. Effect of weight reduction on insulin sensitivity, sex hormone-binding globulin, sex hormones and gonadotrophins in obese children[J]. Eur J Endocrinol, 2010, 163(6): 895-900. |

| [27] | Shi J, Li L, Hong J, et al. Genetic variants determining body fat distribution and sex hormone-binding globulin among Chinese female young adults[J]. J Diabetes, 2014, 6(6): 514-518. |

| [28] | Pilia S, Casini MR, Foschini ML, et al. The effect of puberty on insulin resistance in obese children[J]. J Endocrinol Invest, 2009, 32(5): 401-405. |

| [29] | Kavanagh K, Espeland MA, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Liver fat and SHBG affect insulin resistance in midlife women: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN)[J]. Obesity (Silver Spring), 2013, 21(5): 1031-1038. |

| [30] | Topaloglu AK, Reimann F, Guclu M, et al. TAC3 and TACR3 mutations in familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism reveal a key role for Neurokinin B in the central control of reproduction[J]. Nat Genet, 2009, 41(3): 354-358. |

| [31] | Navarro VM, Castellano JM, McConkey SM, et al. Interactions between kisspeptin and neurokinin B in the control of GnRH secretion in the female rat[J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2011, 300(1): E202-E210. |

| [32] | Navarro VM, Ruiz-Pino F, Sanchez-Garrido MA, et al. Role of neurokinin B in the control of female puberty and its modulation by metabolic status[J]. J Neurosci, 2012, 32(7): 2388-2397. |

| [33] | Kinsey-Jones JS, Grachev P, Li XF, et al. The inhibitory effects of neurokinin B on GnRH pulse generator frequency in the female rat[J]. Endocrinology, 2012, 153(1): 307-315. |

| [34] | Li SY, Li XF, Hu MH, et al. Neurokinin B receptor antagonism decreases luteinising hormone pulse frequency and amplitude and delays puberty onset in the female rat[J]. J Neuroendocrinol, 2014, 26(8): 521-527. |

| [35] | Topaloglu AK, Tello JA, Kotan LD, et al. Inactivating KISS1 mutation and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 366(7): 629-635. |

| [36] | Teles MG, Bianco SD, Brito VN, et al. A GPR54-activating mutation in a patient with central precocious puberty[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 358(7): 709-715. |

| [37] | 刘小辉, 刘芳, 夏治, 等. Kiss-1在雌性性早熟大鼠下丘脑中mRNA的表达[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2007, 9(1): 59-62. |

| [38] | Pita J, Barrios V, Gavela-Perez T, et al. Circulating kisspeptin levels exhibit sexual dimorphism in adults, are increased in obese prepubertal girls and do not suffer modifications in girls with idiopathic central precocious puberty[J]. Peptides, 2011, 32(9): 1781-1786. |

| [39] | Roa J, Vigo E, Garcia-Galiano D, et al. Desensitization of gonadotropin responses to kisspeptin in the female rat: analyses of LH and FSH secretion at different developmental and metabolic states[J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2008, 294(6): E1088-E1096. |

| [40] | Quennell JH, Howell CS, Roa J, et al. Leptin deficiency and diet-induced obesity reduce hypothalamic kisspeptin expression in mice[J]. Endocrinology, 2011, 152(4): 1541-1550. |

| [41] | Navarro VM, Gottsch ML, Wu M, et al. Regulation of NKB pathways and their roles in the control of Kiss1 neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the male mouse[J]. Endocrinology, 2011, 152(11): 4265-4275. |

| [42] | Garcia-Galiano D, van Ingen Schenau D, Leon S, et al. Kisspeptin signaling is indispensable for neurokinin B, but not glutamate, stimulation of gonadotropin secretion in mice[J]. Endocrinology, 2012, 153(1): 316-328. |

2015, Vol. 17

2015, Vol. 17