坏死性小肠结肠炎(necrotizing enterocolitis,NEC)是一种常见的新生儿胃肠道急症,主要发生于早产儿,特别是极低出生体重(very low birth weight,VLBW)早产儿[1]。研究表明VLBW早产儿NEC的发病率可达到10%,而NEC导致的病死率可高达20%~30%[2]。NEC的发病机制目前仍不是很清楚,可能与早产、肠道屏障功能不成熟或肠道黏膜发生缺血再灌注损伤、病原菌侵袭、高渗奶喂养、早产儿肠道菌群少引起优势菌种滋生和移位等有关[3],目前无有效的防治手段。益生菌是一类定植于人体肠道、生殖系统内,能改善宿主微生态平衡、发挥有益作用的活的微生物[4]。近年来研究证实:新生儿,特别是早产儿肠道正常菌群定植延迟或缺乏,致病菌过度生长繁殖可能是NEC发病的主要因素之一,某些益生菌可以预防NEC的发生、降低其严重程度和病死率[5]。益生菌预防NEC的机制目前不是很清楚,可能与促进肠道正常菌群的定植、改善胃肠道黏膜屏障的功能和成熟、抑制致病微生物的定植等有关[2]。许多的临床随机对照试验对益生菌在预防VLBW早产儿NEC和降低病死率方面的安全性和有效性进行了大量的研究。虽然大多数的研究结果表明预防性使用益生菌能降低VLBW早产儿NEC的发病率及病死率,但是益生菌的常规使用仍颇有争议,争议的关键在于以下几点:(1)研究对象的数量有限;(2)某些试验中NEC的发病率或者病死率异常增高;(3)尚未解决的问题,如合适的益生菌菌株,合适的剂量以及预防使用的时间;(4)益生菌在早产儿使用的安全性不确定;(5)不同的喂养方式导致的试验之间的异质性;(6)益生菌对体重<1 000 g以下的患儿的影响的资料不足[6]。因此,本研究运用循证医学的原理和方法,收集当前发表的国内外研究预防性使用益生菌对降低VLBW早产儿NEC的发病率及病死率的原始研究进行客观比较,以评价益生菌在降低NEC发病率和病死率方面的安全性和有效性。 1 资料与方法 1.1 检索策略

计算机检索PubMed、EMBASE、Cochrane临床对照试验资料库(CENTRAL)、the ISI Web of Knowledge Databases、中国生物医学文献数据库(CBM)、中文期刊全文数据库(CNKI)和维普中文科技期刊数据库(VIP)、万方数据库,检索时间均为建库至2014年3月,收集所有研究预防性使用益生菌对降低VLBW早产儿NEC的发病率和病死率的随机对照试验。英文数据库以“very low birth weight infant,low birth weight infant,extremely low birth weight infant,premature infant,preterm infant”和“lactobacillus,probiotics,saccharomyces,bifidbacterium”和“necrotizing enterocolitis,NEC”等为检索词。中文数据库以“极低出生体重儿、早产儿、坏死性小肠结肠炎、益生菌”等为检索词。当试验报告资料不详或资料缺乏,通过电话或邮件与研究的主要作者联系获取,并辅以手工检索纳入文献的参考文献,以尽量增加纳入文献资料。 1.2 文献标准

(1)研究类型:检索文献数据库中截止到2014年3月所有已经发表的国内外研究预防性使用益生菌对降低VLBW早产儿NEC的发病率和病死率的随机对照试验。

(2)研究对象:胎龄<34周、出生体重<1 500 g的VLBW早产儿;生后10 d内开始给予益生菌口服或者鼻饲,并喂养持续至少7 d以上者。

(3)主要测量指标:NEC(Bell分期2期及2期以上)的发生率、血培养阳性的败血症发生率、总病死率、NEC相关病死率。 1.3 文献质量评价

纳入研究的方法学质量采用Jadad评分量表进行评价,总分为5分,1分或2分的试验被视为低质量,3~5分为高质量[7]。 1.4 资料提取

阅读全文后进行资料提取,由2 位评价员独立完成,若遇争议则通过第3 位评价员 介入进行讨论。内容包括研究类型、随机和分组的方法和过程、样本的入选标准和样本量、研究对象的基本资料、干预的措施、测量指标、统计学方法。缺乏的资料通过与作者联系或其他途径进行补充。 1.5 统计学分析

采用Cochrane 协作网提供的RevMan 5.1软件进行。首先对同类研究间的异质性进行评价,若无异质性使用固定效应模型;若具有异质性,则对其异质性来源进行分析,使用随机效应模型。计数资料采用风险比(RR)作为分析统计量。所有分析均计算95%可信区间(CI)。文献质量低者,进行敏感性分析。根据益生菌的种类进行亚组分析。应用Stata 12.0软件进行发表偏倚分析。 2 结果 2.1 纳入研究的一般情况

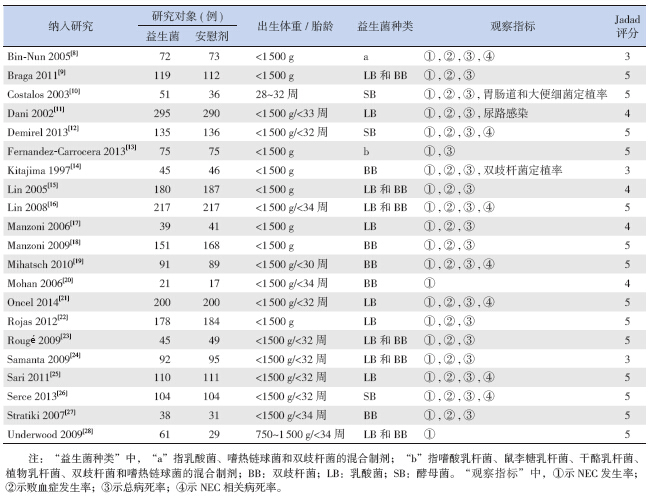

初检出相关文献242篇,先剔除重复文献72篇;经阅读文题和(或)摘要后剔除明显不符合纳入标准的133 篇;进一步剔除重复发表、交叉的和不符合纳入标准的文献16 篇后,纳入21 篇文献[8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28],包括4 607例VLBW早产儿。各文献中患者进行同质性检验,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。纳入研究的一般情况及基线特征见表 1。

| 表 1 纳入研究的一般情况 |

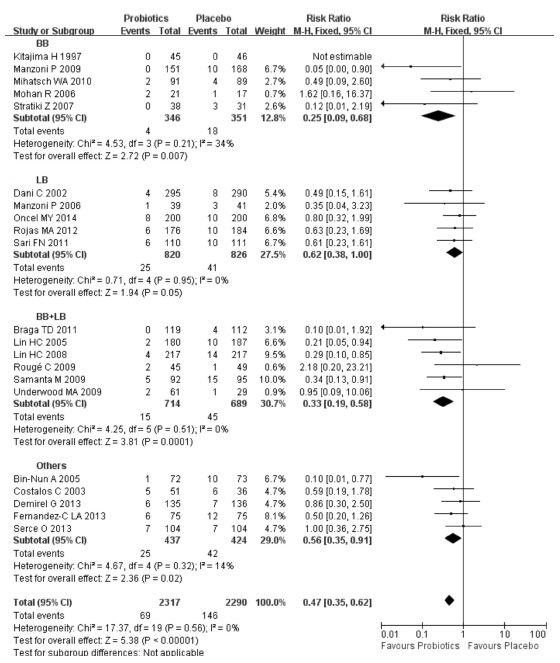

共有21项研究[8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28](纳入4 607例 VLBW早产儿)比较了益生菌对NEC的影响。与安慰剂对照组比较,益生菌组 NEC的发生率下降了53%。研究具有同质性(P=0.56,I2=0%),采用固定效应模型合并分析。Meta 分析结果表明:两组在NEC的发生率上差异有统计学意义[RR=0.47;95%CI(0.35~0.62),P<0.01],预防性使用益生菌组NEC的发生率明显低于安慰剂对照组。亚组分析结果表明双歧杆菌、双歧杆菌和乳酸菌的混合菌株以及纳入文献中的其他菌株均能显著降低VLBW早产儿NEC的发生率,差异有统计学意义;而单独的乳酸菌菌株不能降低VLBW早产儿NEC的发生率(P=0.05)。敏感性分析发现分别剔除21项研究,合并效应量仍都具有统计学意义且森林图结果方向均未发生改变,见图 1。

|

图 1 益生菌对Bell分期≥2期NEC的影响的森林图 |

有18项研究[8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27](纳入4 329例VLBW早产儿)比较了益生菌对血培养阳性败血症发生率的影响。益生菌组血培养阳性342例(15.83%),安慰剂对照组血培养阳性395例(18.21%)。但研究间存在异质性(P=0.01),探讨其异质性来源可能为益生菌种类、剂量及使用时间不同所致,故采用随机效应模式合并分析。Meta分析结果表明:两组血培养阳性的败血症发生率差异无统计学意义[RR=0.87;95%CI(0.72~1.06);P=0.17],提示预防性使用益生菌不会增加VLBW早产儿败血症的发生;亚组分析结果表明益生菌的种类与血培养阳性败血症的发生无明显相关性。敏感性分析发现分别剔除18项研究,合并效应量仍都具有统计学意义且森林图结果方向均未发生改变。 2.4 益生菌对总病死率的影响

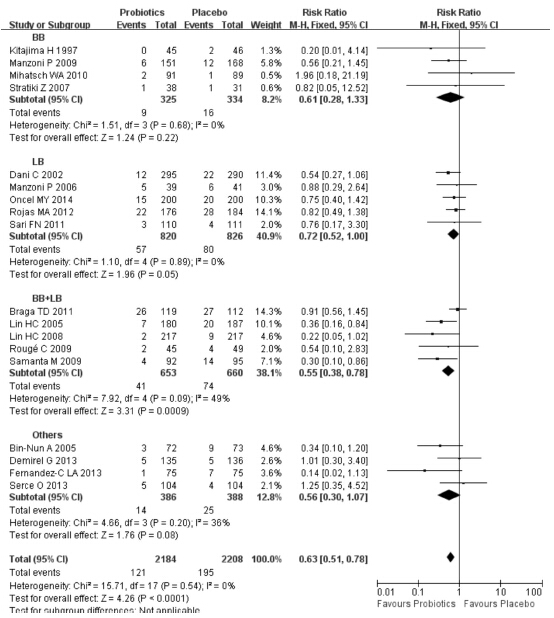

共有18项研究[8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27](纳入4 392例VLBW早产儿)比较了益生菌对总病死率的影响。与安慰剂对照组比较,益生菌组总病死率下降了38%(8.83% vs 5.40%),研究具有同质性(P=0.54,I2=0%),采用固定效应模型合并分析。结果表明:两组总病死率差异有统计学意义[RR=0.63;95%CI(0.51~0.78),P<0.01],益生菌组VLBW早产儿病死率明显低于安慰剂对照组。亚组分析结果表明双歧杆菌和乳酸菌的混合菌株能降低VLBW早产儿的病死率,但其他菌株亚组对VLBW早产儿的病死率无影响(P>0.05)。敏感性分析发现分别剔除18项研究,合并效应量仍都具有统计学意义且森林图结果方向均未发生改变,见图 2。

|

图 2 益生菌对总病死率的影响 |

有7项研究[8, 12, 16, 19, 21, 25, 26](纳入1 859例VLBW早产儿)比较了益生菌对NEC相关病死率的影响。与安慰剂对照组比较,益生菌组NEC相关病死率明显下降(0.97% vs 1.5%),研究具有同质性(P=0.81,I2=0%),采用固定效应模型合并分析,结果表明:两组NEC相关病死率差异无统计学意义 [RR=0.68;95%CI(0.31~1.48),P=0.33]。亚组分析结果表明益生菌种类对NEC相关病死率亦无明显影响。敏感性分析发现分别剔除7项研究,合并效应量仍都具有统计学意义且森林图结果方向均未发生改变。 2.6 发表偏倚

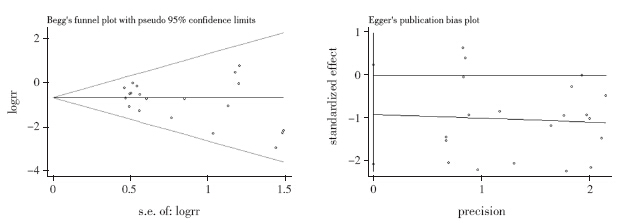

对纳入分析的21篇文献行发表偏倚检验。各观察指标漏斗图基本对称,提示无明显发表偏倚。益生菌对Bell分期≥2期NEC的影响中,Begg's检验Pr>|z|=0.230,Egger's检验P=0.118;益生菌对血培养阳性的败血症发生率的影响中,Begg's检验Pr>|z|=0.225,Egger's检验P=0.241;益生菌对总病死率的影响中,Begg's检验Pr>|z|=0.495,Egger's检验P=0.114;益生菌对NEC相关病死率的影响中,Begg's检验Pr>|z|=0.707,Egger's检验P=0.602,各检验结果均大于0.05,提示无发表偏倚(图 3)。

|

图 3 益生菌对Bell分期≥2期NEC的影响的发表偏倚检验 |

随着NICU的建立和发展以及机械通气的应用,早产儿的存活率明显增加,而NEC的发病率也随之增加,特别是VLBW早产儿,是影响VLBW早产儿死亡的重要原因[29]。VLBW早产儿肠道微生物群的获得主要来源于NICU的环境,其肠道菌群定植及优势化时间明显低于出生体重为1 500~1 999 g之间的早产儿(25% vs 50%)[30]。据报道,VLBW早产儿肠道双歧杆菌的定植可以延迟至生后3周,且肠道菌群定植模式与足月儿不同,肠道内细菌种类缺乏,尤其是双歧杆菌及乳酸杆菌缺乏,而肠道益生菌的补充可促进早产儿肠道正常菌群的定植和优势化,降低VLBW早产儿NEC的发病率和病死率[15]。

关于早产的VLBW预防性使用益生菌的报道并不少见,但由于纳入病例一般情况的差异,包括胎龄、出生体重、益生菌的类型、剂量、益生菌使用的时间及喂养方式等的各不相同,结论各异,且由于大多单个研究样本量存在局限性,因此对益生菌真正的作用缺乏客观评价。本研究采用循证医学方法,重新评价了益生菌在VLBW早产儿的使用及其对VLBW早产儿的影响,结果表明,与安慰剂对照组比较,益生菌的补充能明显的降低VLBW早产儿Bell分期≥2期NEC的发病率和总病死率,而两组之间败血症发生率及NEC相关病死率的差异无统计学意义,分析原因可能与纳入研究病例数较少有关。

益生菌是定植于宿主胃肠道能为宿主提供保护作用的活的微生物,能促进VLBW早产儿肠道正常菌群的定植和优势化[4]。益生菌降低早产儿NEC的发病率和病死率的机制目前不是很清楚,可能与下列因素有关:(1)增加致病菌及其产物在胃肠道黏膜的迁移屏障[31];(2)竞争性的排除致病菌[15];(3)增强分泌型IgA的黏膜防护作用,提高肠道内营养,上调宿主的免疫反应,从而抑制致病微生物的生长。本研究结果表明,与对照组比较,益生菌组NEC的发病率下降了53%,病死率下降了38%。益生菌的补充能明显的降低VLBW早产儿NEC的发病率和总病死率,且未报道益生菌使用过程中特殊的病原体引起的败血症。

本研究纳入文献具有以下局限性:(1)纳入对象的胎龄、出生体重不同;(2)益生菌菌株、喂养方式、剂量及使用时间不同;(3)纳入的研究中未有中文文献;因此,益生菌使用的最适剂量、类型(如种、系、单一或者联合、死菌还是活菌),用药时间等目前还不是很明确。因此,需要更大规模的临床试验,特别是国内的临床试验,来证实益生菌在VLBW早产儿使用的安全性和有效性。

| [1] | Obladen M. Necrotizing enterocolitis-150 years of fruitless search for the cause[J]. Neonatology, 2009, 96(4): 203-210. |

| [2] | Neu J, Walker WA. Necrotizing enterocolitis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2011, 364(3): 255-264. |

| [3] | Hsueh W, Caplan MS, Qu XW, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: clinical considerations and pathogenetic concepts[J]. Pediatr Dev Pathol, 2003, 6(1): 6-23. |

| [4] | Lin PW, Stoll BJ. Necrotising enterocolitis[J]. Lancet, 2006, 368(9543): 1271-1283. |

| [5] | Caplan MS. Probiotic and prebiotic supplementation for the prevention of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis[J]. J Perinatol, 2009, 29(Suppl 2): S2-S6. |

| [6] | Deshpande G, Rao S, Patole S, et al. Updated meta-analysis of probiotics for preventing necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm neonates[J]. Pediatrics, 2010, 125(5): 921-930. |

| [7] | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials blinding necessary?[J]. Controlled Clin Trials, 1996, 17(1): 1-12. |

| [8] | Bin-Nun A, Bromiker R, Wilschanski M, et al. Oral probiotics prevent necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight neonates[J]. J Pediatr, 2005, 147(2): 192-196. |

| [9] | Braga TD, da Silva GA, de Lira PI, et al. Efficacy of Bifido- bacterium breve and Lactobacillus casei oral supplementation on necrotizing enterocolitis in very-low-birth-weight preterm infants: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2011, 93(1): 81-86. |

| [10] | Costalos C, Skouteri V, Gounaris A, et al. Enteral feeding of premature infants with Saccharomyces boulardii[J]. Early Hum Dev, 2003, 74(2): 89-96. |

| [11] | Dani C, Biadaioli R, Bertini G, et al. Probiotics feeding in prevention of urinary tract infection, bacterial sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. A prospective double-blind study[J]. Biol Neonate, 2002, 82(2): 103-108. |

| [12] | Demirel G, Erdeve O, Celik IH, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: A randomized, controlled study[J]. Acta Paediatr, 2013, 102(12): e560-e565. |

| [13] | Fernández-Carrocera LA, Solis-Herrera A, Cabanillas-Ayón M, et al. Double blind, randomised clinical assay to evaluate the efficacy of probiotics in preterm newborns weighing less than 1 500 g in the prevention of necrotising enterocolitis[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2013, 98(1): F5-F9. |

| [14] | Kitajima H, Sumida Y, Tanaka R, et al. Early administration of Bifidobacterium breve to preterm infants: randomised controlled trial[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 1997, 76(2): F101-F107. |

| [15] | Lin HC, Su BH, Chen AC, et al. Oral probiotics reduce the incidence and severity of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants[J]. Pediatrics, 2005, 115(1): 1-4. |

| [16] | Lin HC, Hsu CH, Chen HL, et al. Oral probiotics prevent necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight preterm infants: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial[J]. Pediatrics, 2008, 122(4): 693-700. |

| [17] | Manzoni P, Mostert M, Leonessa ML, et al. Oral supplementation with Lactobacillus casei subspecies rhamnosus prevents enteric colonization by Candida species in preterm neonates: a randomized study[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2006, 42(12): 1735-1742. |

| [18] | Manzoni P, Rinaldi M, Cattani S, et al. Bovine lactoferrin supplementation for prevention of late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: a randomized trial[J]. JAMA, 2009, 302(13): 1421-1428. |

| [19] | Mihatsch WA, Vossbeck S, Eikmanns B, et al. Effect of Bifidobacterium lactis on the incidence of nosocomial infections in very low birth weight infants: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Neonatology, 2010, 98(2): 156-163. |

| [20] | Mohan R, Koebnick C, Schildt J, et al. Effects of Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 supplementation on intestinal microbiota of preterm infants: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2006, 44(11): 4025-4031. |

| [21] | Oncel MY, Sari FN, Arayici S, et al. Lactobacillus Reuteri for the prevention of necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants: a randomised controlled trial[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2014, 99(2): F110-F115. |

| [22] | Rojas MA, Lozano JM, Rojas MX, et al. Prophylactic probiotics to prevent death and nosocomial infection in preterm infants[J]. Pediatrics, 2012,130(5): e1113-e1120. |

| [23] | Rougé C, Piloquet H, Butel MJ, et al. Oral supplementation with probiotics in very-low-birth-weight preterm infants: a randomized,double-blind, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2009, 89(6): 1828-1835. |

| [24] | Samanta M, Sarkar M, Ghosh P, et al. Prophylactic probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight newborns[J]. J Trop Pediatr, 2009, 55(2): 128-131. |

| [25] | Sari FN, Dizdar EA, Oguz S, et al. Oral probiotics: Lactobacillus sporogenes for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low-birth weight infants: a randomized, controlled trial[J]. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2011, 65(4): 434-439. |

| [26] | Serce O, Benzer D, Gursoy T, et al. Efficacy of saccharomyces boulardii on necrotizing enterocolitis or sepsis in very low birth weight infants: a randomised controlled trial[J]. Early Hum Dev, 2013, 89(12): 1033-1036. |

| [27] | Stratiki Z, Costalos C, Sevastiadou S, et al. The effect of a bifidobacter supplemented bovine milk on intestinal permeability of preterm infants[J]. Early Hum Dev, 2007, 83(9): 575-579. |

| [28] | Underwood MA, Salzman NH, Bennett SH, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled comparison of 2 prebiotic/probiotic combinations in preterm infants: impact on weight gain, intestinal microbiota, and fecal short-chain fatty acids[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2009, 48(2): 216-225. |

| [29] | Deshpande G, Rao S, Patole S. Probiotics for prevention of necrotising enterocolitis in preterm neonates with very low birthweight: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials[J]. Lancet, 2007, 369(9573): 1614-1620. |

| [30] | Agarwal R, Sharma N, Chaudhry R, et al. Effects of oral Lactobacillus GG on enteric microflora in low-birth-weight neonates[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2003, 36(3): 397-402. |

| [31] | Li Y, Shimizu T, Hosaka A, et al. Effects of Bifidobacterium breve supplementation on intestinal flora of low birth weight infants[J]. Pediatr Int, 2004, 46(5): 509-515. |

2015, Vol. 17

2015, Vol. 17