2. 昆明医科大学附属儿童医院风湿免疫科, 云南 昆明 650000

过敏性紫癜(Henoch-Schönlein purpura,HSP)是儿童时期最常见的系统性小血管炎[1]。其临床特征是非血小板减少性紫癜性皮疹、非损伤性关节炎、消化道症状及肾炎[2]。近年来儿童HSP发病似有逐年增多的趋势[3]。尽管HSP在儿童中很常见,但其病因和发病机制仍未完全明确[4]。寻找有诊断价值的无创实验室标记物对诊断儿童HSP很有必要。粪便胆汁酸是重要的信号分子,在调节机体免疫及维持促进肠屏障功能方面有重要作用。结肠癌[5]、肠易激综合征[6]、溃疡性结肠炎[7]等疾病的发病均与粪便胆汁酸有关,其也是粪菌移植治疗的调节靶点[8]。HSP患儿粪便胆汁酸研究是探讨HSP发病机制重要和有益的补充。目前还未见粪便胆汁酸与HSP关系的相关报道。因此,本研究借助液相质谱技术检测HSP患儿粪便次级胆汁酸含量,以便利于将其作为一种新的生物标记物或靶点,认识其在诊治HSP患者中的临床意义。

1 资料与方法 1.1 临床资料选取2014~2016年于云南省昆明医科大学第一附属医院儿科确诊为HSP的19例患儿为HSP组,其中男12例,女7例,平均年龄9.5±1.3岁,平均体重26±4 kg。HSP诊断参照中华医学会儿科学分会免疫学组推荐的HSP的诊断(EULAR/PRINTO/PRES统一标准)[9]。排除其他自身免疫性疾病、过敏性疾病或者感染、肿瘤性疾病及消化系统疾病;排除近1周使用抗生素、微生态制剂及激素患者。另选取27例来自学校无疾病和无用药史的健康儿童作为健康对照组,其中男16例,女11例,平均年龄为9.5±2.7岁,平均体重27±5 kg。两组性别、年龄、体重比较差异无统计学意义。

通过对病人详细病史的了解及对其进行全面的体格检查,所有的病人均出现皮疹。2例仅有皮疹表现;17例伴随其他临床表现,其中3例有关节肿痛,2例有肾脏受累,2例有腹痛,9例有腹痛伴关节痛,还有1例表现为关节痛伴腹痛及肾脏受累。该研究经昆明医科大学医学伦理委员会批准,并获得家长知情同意。

1.2 标本收集本研究收集健康儿童1次粪便标本及HSP患儿2次粪便标本。第1次于患儿发病3 d内未使用任何药物前收集(急性期),第2次于患儿临床症状体征消失时收集(恢复期)。被收集的新鲜粪便立即放入-80℃低温冰箱保存。待粪便完全冰冻后在液氮保持的低温环境中分装出0.2 g左右样本于10 mL离心管中用于胆汁酸检测。

1.3 标本预处理粪便标本前处理参照文献[10-11],即将冷冻标本放在室温下,标本一旦解冻加入2 mL甲醇,在涡旋机上涡旋混匀,4 000转/min离心5 min,取上清液通过0.22 μm过滤器入棕色色谱瓶待测。

1.4 主要试剂与仪器所有胆汁酸标准品均为加拿大TRC(Torontoresearch chemicals)标准品。1290超高效液相色谱仪(美国Agilent公司);API4000三重四极杆质谱仪(美国AB公司);ZORBAX RRHD2.1 mm×50 mm×1.8 µm色谱柱(美国Agilent公司)。

1.5 粪便胆汁酸的测定本研究中采用液相质谱检测粪便胆汁酸。液相质谱条件如下:色谱柱ZORBAX RRHD(2.1 mm×50 mm×1.8 µm)。流动相:0.1%甲酸-水(A)-乙腈(B),流速为0.3 mL/min。梯度洗脱:0~5 min,A为95%;5~15 min,A由95%变化至60%;15~15.2 min,A由60%变化至5%,保持5%至17 min;17~17.2 min,A由5%变化至95%,保持95%至19 min。甘氨鹅脱氧胆酸、熊脱氧胆酸、鹅脱氧胆酸、脱氧胆酸、胆酸、石胆酸保留时间依次为13.41、11.71、13.04、13.30、12.00、14.57 min;母离子依次为448.3、391.2、391.2、391.2、407.2、375.3 m/z;碰撞电压依次为-77、-30、-30、-30、-30、-40 V;入口电压均为-10 V;碰撞室出口电压依次为:-11、-20、-20、-20、-20、-20 V。

1.6 统计学分析本研究采用SPSS 17.0统计学软件对数据进行统计学分析。正态分布计量资料以均数±标准差(x±s)表示,多组间比较采用单因素方差分析,组间两两比较采用SNK-q检验;偏态分布计量资料以中位数(四分位间距)[M(P25,P75)]表示,多组间采用Kruskal-Wallis H秩和检验;P≤0.05为差异有统计学意义。多组偏态分布计量资料组间两两比较采用Mann-Whitney U秩和检验,调整检验水准α'=α(0.05)/总比较次数(3),即P<0.016为差异有统计学意义。

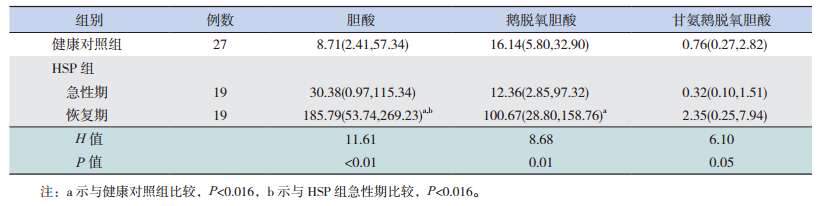

2 结果 2.1 各组初级胆汁酸指标检测结果HSP组患儿急性期胆酸、鹅脱氧胆酸水平与健康对照组比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.016)。HSP组患儿恢复期胆酸、鹅脱氧胆酸水平均高于健康对照组(P<0.016)。HSP组患儿恢复期胆酸水平高于急性期(P<0.016)。各组间甘氨鹅脱氧胆酸水平比较差异有统计学意义(P=0.05),但调整检验水准后行组间两两比较,结果显示差异均无统计学意义(P>0.016)。见表 1。

| 表 1 各组胆酸、鹅脱氧胆酸、甘氨鹅脱氧胆酸水平比较[M(P25, P75), mg/g] |

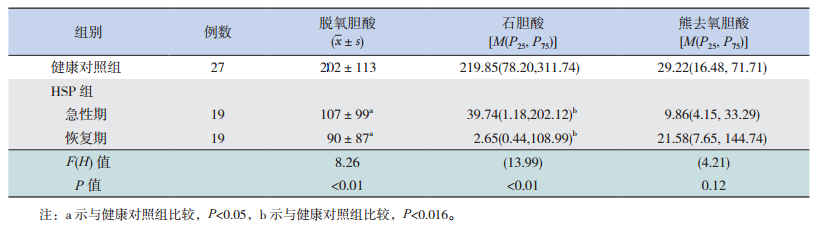

2.2 各组次级胆汁酸检测结果

HSP组患儿急性期和恢复期脱氧胆酸、石胆酸水平均低于健康对照组(分别P<0.05、P<0.016)。HSP组患儿恢复期脱氧胆酸、石胆酸水平与急性期比较,差异无统计学意义(分别P>0.05、P>0.016)。各组间熊去氧胆酸水平比较差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表 2。

| 表 2 各组脱氧胆酸、石胆酸、熊去氧胆酸水平比较(mg/g) |

3 讨论

近些年来关于HSP的研究[12-15]主要是以血标本为切入点探索HSP发病机制。目前研究认为HSP是免疫异常、环境因素、个体遗传综合作用的结果,凝血机制、炎性递质也参与本病发病[16]。最近有研究发现HSP的发生、发展与肠上皮通透性、肠道菌群组成、黏膜免疫密切相关[17]。本课题组前期研究也发现HSP患儿的肠道菌群有紊乱和黏膜屏障有损伤[18-19]。

胆汁酸按来源分为初级胆汁酸和次级胆汁酸。初级胆汁酸由肝细胞直接合成,包括胆酸、鹅脱氧胆酸、甘氨胆酸、甘氨鹅脱氧胆酸、牛磺胆酸、牛磺鹅脱氧胆酸;次级胆汁酸并非由肝细胞产生,而是经肠道细菌分解后形成的产物,包括脱氧胆酸、熊去氧胆酸、石胆酸及其与甘氨酸和牛磺酸的结合产物。

肠腔内胆汁酸是肠道菌群主要的代谢产物[20],不仅能促进物质的消化和吸收[21],还是重要的信号激素[22],通过激活不同组织的受体发挥系统性影响[23]。越来越多的研究还认识到肠腔内胆汁酸是调节肠上皮稳态、转运及肠屏障功能的重要信号分子[24]。综上,了解肠腔内胆汁酸可为诊治相关疾病识别新的生物标记物靶点。了解肠腔内胆汁酸依赖于了解粪便胆汁酸。本研究以HSP患儿粪便标本为切入点,采用液相质谱法对HSP患儿粪便胆汁酸含量行定量检测,探讨粪便胆汁酸在HSP发病中的作用。

本研究发现HSP急性期次级胆汁酸脱氧胆酸、石胆酸含量降低,与健康对照组比较差异有统计学意义。而初级胆汁酸胆酸、鹅脱氧胆酸含量与健康对照组比较则差异无统计学意义。生理浓度的肠内胆汁酸能通过诱导杯状细胞分泌黏液使肠黏膜抵抗脱水、物理损害及细菌侵袭[25],能诱导细胞迁移修复上皮促进受损屏障功能的恢复[26],能促进上皮细胞分泌细胞因子利于免疫监视功能的发挥[27]。Münch等[28]发现低水平的脱氧胆酸能降低结肠组织的跨上皮阻力,即肠上皮通透性增加,能增加结肠组织对细菌量的吸收[29],由此推测在HSP急性期次级胆汁酸降低可能引起肠道通透性增加,有害物质穿过黏膜刺激免疫反应引起HSP发病。次级胆汁酸脱氧胆酸、石胆酸还能通过胆汁酸特异性膜受体TGR5减少促炎因子IL-1α、IL-1β、IL-6及TNF-α的分泌[30]。炎症性肠病患者因肠内次级胆汁酸的减少而加重了病情[31]。已有的研究发现促炎因子在HSP病因中发挥着重要作用[32],可能与HSP病人肠内次级胆汁酸减少有关。

有研究认为肠腔内胆汁酸成分的构成依赖于饮食和结肠内菌群[24]。本研究中HSP患儿病情相对较轻,未对患儿饮食进行特殊控制,且患儿均来自云南地区,文化饮食习惯相同。次级胆汁酸脱氧胆酸、石胆酸是由初级胆汁酸胆酸、鹅脱氧胆酸在肠道微生态作用下分别转化而来[33]。若是由肠道菌群引起本研究中HSP患儿急性期次级胆汁酸减少,则初级胆汁酸会相应的升高,而本研究中初级胆汁酸并未改变。另外本研究未对肠腔内所有的胆汁酸进行检测,且负责各种胆汁酸生物转化的具体菌群现仍未明确,肠道菌群在HSP中的改变还需进一步研究。

本研究结果还发现HSP恢复期次级胆汁酸脱氧胆酸、石胆酸水平低于健康对照组,而初级胆汁酸胆酸、鹅脱氧胆酸水平高于健康对照组,且差异有统计学意义。一方面可能是由于本研究中患儿治疗过程中均会常规予抗生素。有研究报道,抗生素会减少肠道细菌数量[34],从而影响了初级胆汁酸向次级胆汁酸的转化。另一方面可能是由于临床症状体征消失时,肠内环境仍未恢复正常。这也解释了本研究结果HSP急性期初级胆汁酸鹅脱氧胆酸及次级胆汁酸脱氧胆酸、石胆酸水平与恢复期比较均无差异的可能原因。本研究结果显示各组间熊脱氧胆酸及甘氨鹅脱氧胆酸比较差异无统计学意义。可能熊脱氧胆酸及甘氨鹅脱氧胆酸均不参与HSP的发病。

综上,肠内粪脱氧胆酸、石胆酸在HSP发病时含量是减少的,其机制无论是HSP疾病本身导致,还是另有机制导致都是值得进一步深入研究的课题。总之,在某种程度上,本研究中的脱氧胆酸、石胆酸可以为HSP的诊断和治疗提供帮助,而胆酸、鹅脱氧胆酸、脱氧胆酸、石胆酸均可为明确定义HSP恢复期提供参考。因此,应关注生物标记物胆汁酸如胆酸、鹅脱氧胆酸、脱氧胆酸和石胆酸在诊断和治疗HSP中的价值和临床意义。

| [1] | He X, Zhao Y, Li Y, et al. Serum amyloid A levels associated with gastrointestinal manifestations in Henoch-Schönlein purpura[J]. Inflammation,2012, 35 (4) :1251–1255 . |

| [2] | 朱光华, 钮小玲, 黄文彦. 2012年KDIGO紫癜性肾炎临床实践指南解读[J]. 中华实用儿科临床杂志,2013,28 (17) :1291–1293. |

| [3] | 黄雷, 刘爱民, 戴宇文, 等. 儿童过敏性紫癜760例临床分析[J]. 中华皮肤科杂志,2015,48 (1) :11–14. |

| [4] | Yang YH, Yu HH, Chianq BL. The diagnosis and classification of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: an updated review[J]. Autoimmun Rev,2014, 13 (4-5) :355–358 . |

| [5] | Ou J, DeLany JP, Zhang M, et al. Association between low colonic short-chain fatty acids and high bile acids in high colon cancer risk populations[J]. Nutr Cancer,2012, 64 (1) :34–40 . |

| [6] | Duboc H, Rainteau D, Rajca S, et al. Increase in fecal primary bile acids and dysbiosis in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome[J]. Neuroqastroenterol Motil,2012, 24 (6) :513–520 . |

| [7] | Duboc H, Rajca S, Rainteau D, et al. Connecting dysbiosis, bile-acid dysmetabolism and gut inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Gut,2013, 62 (4) :531–539 . |

| [8] | Weingarden AR, Dosa PI, DeWinter E, et al. Changes in colonic bile acid composition following fecal microbiota transplantation are sufficient to control clostridium difficile germination and growth[J]. PLoS One,2016, 11 (1) :e0147210. |

| [9] | 中华医学会儿科学分会免疫学组, 《中华儿科杂志》编辑委员会. 儿童过敏性紫癜循证诊治建议[J]. 中华儿科杂志,2013,51 (7) :502–507. |

| [10] | Zhang Y, Guo X, Guo J, et al. Lactobacillus casei reduces susceptibility to type 2 diabetes via microbiota-mediated body chloride ion influx[J]. Sci Rep,2014, 4 :5654. |

| [11] | John C, Werner P, Worthmann A, et al. A liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry-based method for the simultaneous determination of hydroxy sterols and bile acids[J]. J Chromatogr A,2014, 1371 :184–195 . |

| [12] | Chen T, Jia RZ, Guo ZP, et al. Elevated serum interleukin-33 levels in patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura[J]. Arch Dermatol Res,2013, 305 (2) :173–177 . |

| [13] | Chen O, Zhu XB, Ren H, et al. The imbalance of Th17/Treg in Chinese children with Henoch-schönlein purpura[J]. Int Immunopharmacol,2013, 16 (1) :67–71 . |

| [14] | López-Mejías R, Genre F, Pérez BS, et al. Association of HLA-B*41:02 with Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (IgA Vasculitis) in Spanish individuals irrespective of the HLA-DRB1 status[J]. Arthritis Res Ther,2015, 17 :102. |

| [15] | Yang YH, Tsai IJ, Chang CJ, et al. The interaction between circulating complement proteins and cutaneous microvascular endothelial cells in the development of childhood Henoch-Schönlein Purpura[J]. PLoS One,2015, 10 (3) :e0120411. |

| [16] | 王凤英, 鲁曼. 过敏性紫癜患儿外周血单个核细胞细胞因子信号转导抑制蛋白1、3 mRNA的表达[J]. 临床儿科杂志,2015,33 (1) :60–63. |

| [17] | 谢志玉, 邱光钰. 肠粘膜屏障功能与儿童过敏性紫癜的相关性分析[J]. 中国实验诊断学,2015,19 (8) :1396–1397. |

| [18] | 娄俊丽, 黄永坤, 刘梅, 等. 住院8天过敏性紫癜患儿肠道菌群的变化研究[J]. 中国微生态学杂志,2009,21 (5) :410–414. |

| [19] | 高晓琳, 黄永坤, 刘梅, 等. 过敏性紫癜患儿胃肠黏膜屏障变化研究[J]. 中国实用儿科杂志,2010,25 (4) :286–288. |

| [20] | Devlin AS, Fischbach MA. A biosynthetic pathway for a prominent class of microbiota-derived bile acids[J]. Nat Chem Biol,2015, 11 (9) :685–690 . |

| [21] | Chiang JY. Bile acids: regulation of synthesis[J]. J Lipid Res,2009, 50 (10) :1955–1966 . |

| [22] | Houten SM, Watanabe M, Auwerx J. Endocrine functions of bile acids[J]. EMBO J,2006, 25 (7) :1419–1425 . |

| [23] | Bajor A, Gillberg PG, Abrahamsson H. Bile acids: short and long term effects in the intestine[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol,2010, 45 (6) :645–664 . |

| [24] | Keating N, Keely SJ. Bile acids in regulation of intestinal physiology[J]. Curr Gastroenterol Rep,2009, 11 (5) :375–382 . |

| [25] | Barcelo A, Claustre J, Toumi F, et al. Effect of bile salts on colonic mucus secretion in isolated vascularly perfused rat colon[J]. Dig Dis Sci,2001, 46 (6) :1223–1231 . |

| [26] | Strauch ED, Yamaquchi J, Bass BL, et al. Bile salts regulate intestinal epithelial cell migration by nuclear factor-kappa B-induced expression of transforming growth factor-beta[J]. J Am Coll Surg,2003, 197 (6) :974–984 . |

| [27] | Mühlbauer M, Allard B, Bosserhoff AK, et al. Differential effects of deoxycholic acid and taurodeoxycholic acid on NF-kappa B signal transduction and IL-8 gene expression in colonic epithelial cells[J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol,2004, 286 (6) :G1000–G1008 . |

| [28] | Münch A, Ström M, Söderholm JD. Dihydroxy bile acids increase mucosal permeability and bacterial uptake in human colon biopsies[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol,2007, 42 (10) :1167–1174 . |

| [29] | Münch A, Söderholm JD, Ost A, et al. Low levels of bile acids increase bacterial uptake in colonic biopsies from patients with collagenous colitis in remission[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther,2011, 33 (8) :954–960 . |

| [30] | Keitel V, Donner M, Winandy S, et al. Expression and function of the bile acid receptor TGR5 in Kupffer cells[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun,2008, 372 (1) :78–84 . |

| [31] | Duboc H, Rajca S, Rainteau D, et al. Connecting dysbiosis, bile-acid dysmetabolism and gut inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Gut,2013, 62 (4) :531–539 . |

| [32] | Nalbantoglu S, Tabel Y, Mir S, et al. Lack of association between macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene promoter (-173 G/C) polymorphism and childhood Henoch-Schönlein purpura in Turkish patients[J]. Cytokine,2013, 62 (1) :160–164 . |

| [33] | Ridlon JM, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria[J]. J Lipid Res,2006, 47 (2) :241–259 . |

| [34] | Miyata M, Hayashi K, Yamakawa H, et al. Antibacterial drug treatment increases intestinal bile acid absorption via elevated levels of ileal apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter but not organic solute transporter α protein[J]. Biol Pharm Bull,2015, 38 (3) :493–496 . |

2016, Vol. 18

2016, Vol. 18