支气管哮喘是最常见的严重的儿童慢性疾病[1]。过去30年里,在世界范围内,哮喘的发病持续增加[2]。很多证据表明,人类微生物组在哮喘的发展中起着重要作用[3]。人类微生物组由人体和生活在人体的微生物的基因组及基因产物共同组成[4-5]。它在保护性免疫应答中起着重要作用[6]。微生物的变化,特别是在产前、围产期及新生儿时期,可能会导致哮喘的发病[7]。研究发现新生儿期接受过抗生素治疗的儿童的哮喘发生率增加[8];而且通过剖宫产出生的儿童哮喘的风险也增加[9-10]。研究表明母乳喂养>6个月可降低儿童哮喘的发病率[11]。亦有国外其他文献报道孕母产前使用抗生素、胎龄、出生体重、新生儿期添加益生菌等因素与儿童哮喘的发病有关[12-16]。而目前国内相关文献报道尚较少。因此为了探讨儿童哮喘与生命早期的众多因素的相关性,本研究回顾性分析了我院306例哮喘儿童的围产期情况,旨在了解各因素对儿童哮喘发病的影响,为哮喘防治提供思路。报道如下。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象选取2011年1月至2016年6月期间在本院确诊为支气管哮喘且孕母资料及新生儿资料相对完整的306例儿童为哮喘组。同时选择同期体检的250例正常儿童为对照组。

纳入标准:入选的哮喘组≥6岁的儿童均符合支气管哮喘的诊断标准[17]。关于<6岁的儿童,目前尚无特异性检测方法和指标作为哮喘的确诊依据。本院对于<6岁的儿童哮喘的诊断,参照儿童支气管哮喘的诊断标准[17],主要依据患儿既往病史、临床症状、体征,并除外其他疾病所引起的喘息、咳嗽、气促和胸闷,结合潮气呼吸肺功能测定[18]、支气管舒张试验、FeNO及过敏原等综合评估诊断。对照组儿童为正常出生且体格发育正常,近半年无呼吸道感染史,无外伤、手术史,无过敏性疾病史。

排除标准:自身免疫性疾病、其他系统感染、慢性疾病。

1.2 临床资料收集(1)母亲因素:孕期吸烟史、孕期服用抗生素史、妊娠期高血压(妊高征)、孕母年龄、分娩方式、产次等情况。(2)新生儿因素:性别、胎龄、出生体重、窒息、喂养方式、新生儿高胆红素血症需光疗者、服用益生菌史等情况。

1.3 统计学分析采用SPSS 19.0 统计软件进行统计学分析,计量资料采用均数± 标准差(x±s)表示,两组比较采用t检验;计数资料以率(%)表示,两组比较采用χ2检验。影响因素分析采用多因素logistic回归分析,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 一般情况哮喘组306例患儿中,男198例,女108例,年龄1.5~14.0岁,平均年龄6.2±3.3岁;对照组250例中,男166例,女84例,年龄1.1~14.0岁,平均年龄6.0±3.1岁。两组在性别及年龄上比较差异无统计学意义(χ2=0.175,t=1.102,均P<0.05)。

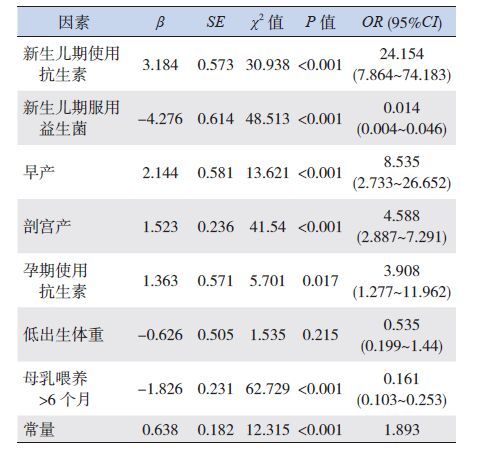

2.2 支气管哮喘的围生期危险因素分析单因素分析发现哮喘组和对照组间差异有统计学意义的因素有:孕期及新生儿期使用抗生素、早产、剖宫产、低出生体重、新生儿期服用益生菌、母乳喂养>6个月(均P<0.05)。将单因素分析有意义的因素作为变量进行多因素logistic回归分析,结果显示:孕期及新生儿期使用抗生素、早产、剖宫产为儿童哮喘的独立危险因素;新生儿期服用益生菌、母乳喂养>6个月为儿童哮喘的保护因素,见表 1~2。

| 表 1 支气管哮喘的单因素分析 [例(%)] |

| 表 2 支气管哮喘的多因素logistic 回归分析 |

3 讨论

许多研究已证实多种慢性成年疾病与妊娠期不良的宫内外环境相关[19]。那么哮喘的发生是否与孕期及新生儿期的因素有关,若能确定这些危险因素或保护因素,尽早进行有效干预,对降低儿童哮喘的发病将是十分有益的。

人类微生物组在人体中起共生作用,它可以通过促进免疫球蛋白产生和调节淋巴细胞功能并产生细胞因子等影响着人体免疫系统的发展[3, 20]。研究显示,在过敏性疾病的病因中,微生物可通过改变早期的胃肠道或呼吸道菌群的定植,导致免疫反应失调和过敏性疾病(如哮喘)增加[21]。新生儿的肠道菌群的建立是一个关键的发展阶段。许多围产期因素可能是通过干扰的肠道菌群而增加哮喘的发病风险。研究显示,子宫最初的着床、胎盘、母体生殖道、分娩方式、喂养方式可能是儿童最初微生物定植的主要来源[22-23]。另外,抗生素的使用也影响微生物定植[8, 24]。如果微生物组改变,可能导致变应性疾病如哮喘等疾病的发生风险增加[3, 20]。

研究显示如果母亲在怀孕的任何时候使用抗生素,孩子患哮喘的风险会增加[13]。本研究显示孕期使用抗生素的儿童患哮喘风险增加,与上述报道一致。有研究显示可能的机制为在妊娠中,胎盘的微生物产生的代谢物和免疫因子,并产生一个平衡的粘膜免疫系统[25]。产妇使用抗生素改变了子宫内及阴道的微生物菌群结构[22, 26]。这种微生物的变化打破了胎盘的平衡免疫系统,并在怀孕期间或分娩过程中传递给胎儿[27-28]。当胎儿微生物的暴露受到干扰时,发生特应性免疫应答使得哮喘的风险增加[29]。

关于母乳喂养与哮喘发病的关系,有研究认为两者无明显相关性[30-31],但也有研究认为母乳喂养可降低哮喘的发病率[11],一项荟萃分析表明,母乳喂养至少6个月可降低哮喘的发病率,按年龄分层后,母乳喂养与在2岁内哮喘的发病有一个强烈的相关性,但该相关性随着年龄的增长而减弱[11]。本研究发现母乳喂养>6个月者是哮喘发生的保护因素,可能的机制为,母乳喂养是婴儿接触的第一个也是最重要的一个暴露因素,母乳中的微生物和低聚糖的存在与儿童肠道菌群的建立密切相关。有证据表明,特定的微生物选择从母亲的肠道,并通过树突状细胞运到乳腺,分泌特异性免疫因子引导儿童微生物的建立[32]。母乳中的低聚糖进入肠道后不被消化,是双歧杆菌理想的培养基,促进婴儿肠道菌群的早期定植[33]。因此相比于奶粉喂养,母乳喂养的儿童其肠道菌群更为丰富,特别是双歧杆菌,从而降低哮喘发病率。

研究显示,新生儿期接受过抗生素治疗的儿童,肠道微生物种类降低,且倾向于某一菌类占主导地位,微生物的结构稳定性降低,肠道菌基因组和抗生素耐药性基因表达会在治疗期间迅速上升,治疗结束后迅速下降,但有一种抗药基因在细菌之间传播,会在抗生素治疗结束后活跃很长时间,从而导致变应性疾病如哮喘等发病率增加[8]。而新生儿期未接触过抗生素的儿童,其肠道菌群则较为丰富且分布均衡。本研究显示哮喘组儿童新生儿期接受过抗生素的比例明显高于对照组,可能与当婴儿开始建立自己的微生物组时,抗生素的使用会影响儿童微生物组菌群结构及微生物的多样性有关[8]。

研究发现通过剖宫产出生的儿童哮喘的风险增加了20%[34]。剖宫产与阴道分娩的儿童微生物组有明显差异,剖宫产儿童在最初6个月内其肠道菌群结构较为单一,丰富度较低[22]。另外,分娩方式会导致婴儿不同细菌的定植,可影响肠道菌群改变。通过剖宫产的儿童,主要是皮肤菌群如金黄色葡萄球菌及棒状杆菌的定植,而阴道分娩的婴儿则是阴道和粪便菌群如乳酸杆菌及普雷沃菌的定植[35]。本研究显示哮喘组儿童剖宫产出生的比例明显高于对照组,与国外研究一致[9-10]。可能与不能及时建立正常的肠道菌群和免疫应答能力,不能有效抑制免疫反应有关[36]。

Jaakkola等[14]的荟萃分析显示胎龄<37周与1岁到31岁哮喘的发病相关,且随着年龄增长哮喘患病率下降。一项包括874710名儿童的荟萃分析也显示,胎龄<37周发生哮喘机率增加1.46倍,且胎龄<32周的儿童比胎龄32~36周患哮喘机率明显升高[37]。本研究显示早产儿发生哮喘的风险是足月儿的8.535倍,早产儿往往肺发育不成熟,肺功能低下,呼吸道疾病发生率升高,导致气道损伤和气道高反应性,同时早产儿呼吸道菌群及肠道菌群建立晚,结构容易单一,导致免疫反应失调,从而使得哮喘发病率增加。

研究证实早期添加益生菌能改善哮喘的症状 [16, 38, 39]。本研究发现添加益生菌者患哮喘风险显著降低。与上述报道一致。

综上,人类微生物组参与人体免疫应答,菌群失调时过敏性疾病如哮喘发病明显增加。建议从避免肠道菌群失调及尽早添加益生菌重建肠道菌群两方面着手,尽早干预孕期及新生儿期影响哮喘发病的因素,从而起到预防及治疗哮喘的作用。

| [1] | Malveaux FJ. The state of childhood asthma:introduction[J]. Pediatrics, 2009, 123 (Suppl 3): S129–S130. |

| [2] | Eder W, Ege MJ, von Mutius E. The asthma epidemic[J]. N Engl J Med, 2006, 355 (21): 2226–2235. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra054308 |

| [3] | Bisgaard H, Hermansen MN, Buchvald F, et al. Childhood asthma after bacterial colonization of the airway in neonates[J]. N Engl J Med, 2007, 357 (15): 1487–1495. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa052632 |

| [4] | Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, et al. The human microbiome project[J]. Nature, 2007, 449 (7164): 804–810. DOI:10.1038/nature06244 |

| [5] | Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome[J]. Science, 2006, 312 (5778): 1355–1359. DOI:10.1126/science.1124234 |

| [6] | Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, et al. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system[J]. Cell, 2005, 122 (1): 107–118. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007 |

| [7] | Penders J, Thijs C, van den Brandt PA, et al. Gut microbiota composition and development of atopic manifestations in infancy:the KOALA Birth Cohort Study[J]. Gut, 2007, 56 (5): 661–667. DOI:10.1136/gut.2006.100164 |

| [8] | Yassour M, Vatanen T, Siljander H, et al. Natural history of the infant gut microbiome and impact of antibiotic treatment on bacterial strain diversity and stability[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2016, 8 (343): 343ra81. DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.aad0917 |

| [9] | Thavagnanam S, Fleming J, Bromley A, et al. A meta-analysis of the association between Caesarean section and childhood asthma[J]. Clin Exp Allergy, 2008, 38 (4): 629–633. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02780.x |

| [10] | Tollånes MC, Moster D, Daltveit AK, et al. Cesarean section and risk of severe childhood asthma:a population-based cohort study[J]. J Pediatr, 2008, 153 (1): 112–116. DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.01.029 |

| [11] | Dogaru CM, Nyffenegger D, Pescatore AM, et al. Breastfeeding and childhood asthma:systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2014, 179 (10): 1153–1167. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwu072 |

| [12] | Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2011, 108 (Suppl 1): 4554–4561. |

| [13] | Stensballe LG, Simonsen J, Jensen SM, et al. Use of antibiotics during pregnancy increases the risk of asthma in early childhood[J]. J Pediatr, 2013, 162 (4): 832–838. DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.09.049 |

| [14] | Jaakkola JJ, Ahmed P, Ieromnimon A, et al. Preterm delivery and asthma:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2006, 118 (4): 823–830. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.06.043 |

| [15] | Mu M, Ye S, Bai MJ, et al. Birth weight and subsequent risk of asthma:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Heart Lung Circ, 2014, 23 (6): 511–519. DOI:10.1016/j.hlc.2013.11.018 |

| [16] | Toh ZQ, Anzela A, Tang ML, et al. Probiotic therapy as a novel approach for allergic disease[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2012, 3 : 171. |

| [17] | 中华医学会儿科分会呼吸学组, 《中华儿科杂志》编辑委员会. 儿童支气管哮喘诊断与防治指南[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2016, 54 (3): 167–181. |

| [18] | 陈育智. 儿童支气管哮喘的诊断及治疗[M].第2版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2010: 78. |

| [19] | Asthma Workgroup, Chinese Thoracic Society, Chinese Societ of General Practitioners. Chinese guideline for the prevention and management of bronchial asthma (Primary Health Care Version)[J]. J Thorac Dis, 2013, 5 (5): 667–677. |

| [20] | Huang YJ, Boushey HA. The microbiome in asthma[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2015, 135 (1): 25–30. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.011 |

| [21] | Lynch SV, Boushey HA. The microbiome and development of allergic disease[J]. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, 2016, 16 (2): 165–171. DOI:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000255 |

| [22] | Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, et al. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010, 107 (26): 11971–11975. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1002601107 |

| [23] | Shilts MH, Rosas-Salazar C, Tovchigrechko A, et al. Minimally invasive sampling method identifies differences in taxonomic richness of nasal microbiomes in young infants associated with mode of delivery[J]. Microb Ecol, 2016, 71 (1): 233–242. DOI:10.1007/s00248-015-0663-y |

| [24] | Collier CH, Risnes K, Norwitz ER, et al. Maternal infection in pregnancy and risk of asthma in offspring[J]. Matern Child Health J, 2013, 17 (10): 1940–1950. DOI:10.1007/s10995-013-1220-2 |

| [25] | Romano-Keeler J, Weitkamp JH. Maternal influences on fetal microbial colonization and immune development[J]. Pediatr Res, 2015, 77 (1-2): 189–195. DOI:10.1038/pr.2014.163 |

| [26] | Isolauri E, Rautava S, Salminen S. Probiotics in the development and treatment of allergic disease[J]. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 2012, 41 (4): 747–762. DOI:10.1016/j.gtc.2012.08.007 |

| [27] | Rautava S, Luoto R, Salminen S, et al. Microbial contact during pregnancy, intestinal colonization and human disease[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2012, 9 (10): 565–576. DOI:10.1038/nrgastro.2012.144 |

| [28] | Rautava S, Collado MC, Salminen S, et al. Probiotics modulate host-microbe interaction in the placenta and fetal gut:a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Neonatology, 2012, 102 (3): 178–184. DOI:10.1159/000339182 |

| [29] | Yazdanbakhsh M, Kremsner PG, van Ree R. Allergy, parasites, and the hygiene hypothesis[J]. Science, 2002, 296 (5567): 490–494. DOI:10.1126/science.296.5567.490 |

| [30] | Lodge CJ, Tan DJ, Lau MX, et al. Breastfeeding and asthma and allergies:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Acta Paediatr, 2015, 104 (467): 38–53. |

| [31] | Brew BK, Allen CW, Toelle BG, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis investigating breast feeding and childhood wheezing illness[J]. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 2011, 25 (6): 507–518. DOI:10.1111/ppe.2011.25.issue-6 |

| [32] | Rodríguez JM. The origin of human milk bacteria:is there a bacterial entero-mammary pathway during late pregnancy and lactation?[J]. Adv Nutr, 2014, 5 (6): 779–784. DOI:10.3945/an.114.007229 |

| [33] | Bode L. Human milk oligosaccharides:every baby needs a sugar mama[J]. Glycobiology, 2012, 22 (9): 1147–1162. DOI:10.1093/glycob/cws074 |

| [34] | Huang L, Chen Q, Zhao Y, et al. Is elective cesarean section associated with a higher risk of asthma? A meta-analysis[J]. J Asthma, 2015, 52 (1): 16–25. DOI:10.3109/02770903.2014.952435 |

| [35] | Woodcock A, Moradi M, Smillie FI, et al. Clostridium difficile, atopy and wheeze during the first year of life[J]. Pediatr Allergy Immunol, 2002, 13 (5): 357–360. DOI:10.1034/j.1399-3038.2002.01066.x |

| [36] | O'Shea TM, Klebanoff MA, Signore C. Delivery after previous cesarean:long-term outcomes in the child[J]. Semin Perinatol, 2010, 34 (4): 281–292. DOI:10.1053/j.semperi.2010.03.008 |

| [37] | Been JV, Lugtenberg MJ, Smets E, et al. Preterm birth and childhood wheezing disorders:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. PLoS Med, 2014, 11 (1): e1001596. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001596 |

| [38] | Yu J, Jang SO, Kim BJ, et al. The effects of lactobacillus rhamnosus on the prevention of asthma in a murine model[J]. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res, 2010, 2 (3): 199–205. DOI:10.4168/aair.2010.2.3.199 |

| [39] | Hougee S, Vriesema AJ, Wijering SC, et al. Oral treatment with probiotics reduces allergic symptoms in ovalbumin-sensitized mice:a bacterial strain comparative study[J]. Int Arch Allergy Immunol, 2010, 151 (2): 107–117. DOI:10.1159/000236000 |

2017, Vol. 19

2017, Vol. 19