2. 湖南师范大学附属长沙医院(长沙市第四医院), 湖南 长沙 410006

急性肾损伤(acute kidney injury, AKI)是小儿先天性心脏病体外循环(cardiopulmonary bypass, CPB)手术后常见的一种并发症,其发生主要与长时间应用CPB有关,但机制尚未完全阐明。合并AKI使住院时间和重症监护室(intensive care unit, ICU)时间延长,腹透、血透等医疗资源占用增加,死亡率显著增高[1-2]。小儿先心病CPB术后AKI发生的危险因素包括低龄、低体重、复杂手术、术前机械通气、术中深低温停循环等等[3],因此需要识别可调节的危险因素来预防或逆转AKI。贫血、低蛋白血症、高血糖、高乳酸等已被证实与成人心脏病术后AKI的预后有关[4],但儿童CPB手术后AKI发生的影响因素鲜见报道。本研究回顾性分析中南大学湘雅医院CPB术后合并AKI的先心病患儿围术期资料,探讨有无改善预后的可调节因素,为此类患者提高术后存活率提供理论依据。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象以2012~2015年中南大学湘雅医院心脏大血管外科资料完整的118例18岁以下先心病CPB术后合并AKI的患者为研究对象。AKI诊断根据急性肾损伤网络(acute kidney injury network, AKIN)标准[5]:血肌酐在术后48 h内上升≥26.5 μmol/L(0.3 mg/dL)或≥术前基础值的1.5倍。排除标准:(1)术前合并肾脏疾病或术前血肌酐≥110 μmol/L;(2)术后48 h内死亡或资料不全;(3)住院期间多次手术。见图 1。

|

图 1 项目流程图 |

所有入组患儿采用心脏外科统一标准的麻醉、手术、CPB和ICU术后监护[6]。咪达唑仑和维库溴铵诱导麻醉,芬太尼和异氟醚吸入维持。正中开胸,CPB下修补心脏畸形。心肌保护采用间断性灌注4 : 1含血高钾停跳液(简称血灌)或全晶体液(Custodial液,简称晶灌)。CPB用平流滚轴泵灌注,以晶胶体和血制品预充小儿膜肺、管道及插管,术中维持活化凝血时间≥480 s、灌注流量每分钟100~150 mL/kg、血红蛋白(Hb)7~8 g/dL(新生儿10 g/dL)、中-浅低温(27~34℃)。心脏畸形纠正后开始复温,停机前鼻咽温37.0℃、肛温35.0℃以上。有需要时超滤至Hb>10 g/dL,使用正性肌力药物。血流动力学稳定后中和肝素,关胸后送至ICU。

术前采集资料包括性别、手术时年龄、体重、有无紫绀、术前诊断和先天性心脏病手术风险评估共识(the risk adjustment for congenital heart sugery-1, RACHS-1)评分、术前有无使用正性肌力药物、有无机械通气、是否急诊手术。根据患儿术前主要的心脏畸形进行RACHS-1评分[7-9],记为1~5分。以最接近手术日期的术前血肌酐值(μmol/L)、血糖值(mmol/L)和乳酸值(mmol/L)作为术前基础值。术中采集资料:CPB时间、阻断升主动脉(occlusion of aorta, OA)时间、是否多次OA、心肌保护方式、是否超滤、是否深低温停循环(deep hypothermia circulation arrest, DHCA)或低流量灌注(低于目标灌注流量的一半以上)、平均Hb(g/dL)、平均血糖值(mmol/L)和平均乳酸值(mmol/L)。术后采集资料:住院时间、ICU时间、机械通气时间,有无采用肾脏替代疗法(renal replace treatment, RRT)即腹透、血透或连续性体外血液净化;术后48 h内血清肌酐的最高值及AKI的严重程度分级(1级:1.5~ < 2倍基础值;2级:2~ < 3倍基础值;3级:≥3倍基础值);术后48 h内使用的正性肌力药物分值(inotropic score, IS),IS(μg/kg/min)=多巴胺+多巴酚丁胺+米力农×15+肾上腺素×100 +去甲肾上腺素×100 +异丙肾上腺素×100;术后输血。

所有病例均随访至2016年12月,死亡或失访为事件终点,以随访结束时是否存活分成存活组(110例)和死亡组(18例),进行两组围手术期各因素的比较,对于其中差异有统计学意义的围术期可调节因素(平均血糖、术后红细胞输注、术后其他血制品输注)进行死亡的关联分析。术中血糖按围术期血糖标准[10]分为三级:≤8.3 mmol/L、>8.3~11.1 mmol/L、>11.1 mmol/L。术后红细胞或其他血制品输注按文献标准[11]分为4级:术后未输注(0),< 40 mL/kg,40~ < 80 mL/kg,≥80 mL/kg。

1.3 统计学分析采用SPSS 23.0软件进行数据处理。正态分布的计量资料以均数±标准差(x±s)表示,组间比较采用t检验;非正态分布资料以中位数四分位数间距[P50(P25,P75)]表示,组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验;计数资料以百分数(%)表示,组间比较采用卡方检验;等级资料采用Willcoxon秩和检验;线性关联分析采用趋势卡方检验;生存分析采用Kplan-Meier分析进行。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 一般资料分析CPB术后AKI的发生率为14.0%(133/949),见图 1;其中资料完整纳入研究的118例患者的中位年龄为12.5(4,45)个月,中位体重8.2(5.1,14.5)kg,男性59例(50.0%);病种包括肺动脉闭锁、法洛四联症、大动脉转位、主动脉弓发育不良或离断、房室管畸形、瓣膜畸形、肺静脉异位引流、房间隔或室间隔缺损、心内膜垫缺损、动脉导管未闭等一种或多种心脏畸形;截止至随访日期,有18例死亡,死亡率为15.3%(18/118),死亡原因见表 1。

| 表 1 18例CPB术后合并AKI死亡患儿的原因分析 |

|

|

纳入研究的118例AKI患者中,AKI损伤分级为1级的占56.8%(67/118),2级占25.4%(30/118),3级占17.8%(21/118);15例进行RRT治疗(AKI 3级12例、AKI 2级3例)的患儿中7例死亡,多发生于复杂先心病;RACHS-1 3~5分的占69.5%(82/118);平均CPB时间130±83 min,平均住院时间18±8 d,中位ICU时间119(68,240)h。

2.2 存活组和死亡组的临床资料分析存活组和死亡组的性别、年龄、体重以及小于2月龄婴儿所占比例的差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);死亡组患者的紫绀型先心病所占比例、RACHS-1分值均高于存活组(P < 0.01);死亡组CPB时间、OA时间、采用晶灌进行心肌保护的比例、术中平均血糖均高于存活组(P < 0.05);死亡组术后的IS、术后肌酐值、3级AKI所占比例、RRT治疗的比例、红细胞及其它血制品输注数量均大于存活组(P < 0.05)。见表 2。

| 表 2 存活组和死亡组的临床资料对比 |

|

|

对于差异有统计学意义的3个围术期可调节因素:术中平均血糖、术后红细胞输注、术后其他血制品输注进行与死亡关系的线性关联分析,发现仅术中平均血糖与死亡存在线性关联(P < 0.05)。见表 3。

| 表 3 围术期可调节因素与死亡的线性关联分析 [n(%)] |

|

|

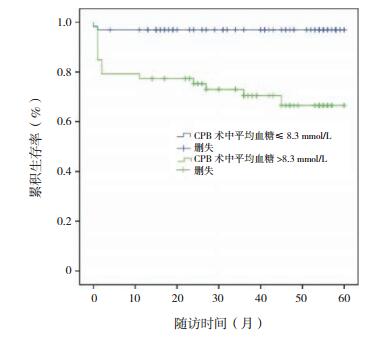

以CPB术中血糖均值8.3 mmol/L为界,分为≤8.3 mmol/L和>8.3 mmol/L两组,作Kplan-Meier生存分析,发现血糖≤8.3 mmol/L组的累积生存率高于>8.3 mmol/L组(分别为96.9%和69.8%,P < 0.01),见图 2;其平均生存期(58.2±1.3个月)高于血糖>8.3 mmol/L组(44.2±3.4个月),差异有统计学意义(χ2=15.567,P < 0.01)。

|

图 2 术中不同血糖值患儿的生存曲线 |

先心病CPB术后合并AKI使住院时间延长、医疗资源消耗增加、死亡率增加[12]。据报道[13],先心病患儿CPB手术的AKI发生率10%~45%,新生儿甚至高达60%,严重影响预后。本研究先心病患儿CPB手术后AKI的发生率为14.0%,AKI患儿的死亡率为15.3%,接近文献报道。复杂畸形、CPB手术时间长的先心病患儿术后更容易发生AKI [14]。本研究CPB术后发生AKI的患儿中RACHS-1评分3~5分的占69.5%、平均CPB时间大于2 h,与文献相符,提示应尽量缩短CPB手术时间,并探索长时间CPB手术如何预防AKI发生的方法。既往研究认为,CPB术后发生AKI患儿的年龄越小、AKI 3级、需要RRT治疗的先心病患儿死亡率较高[15-17]。本研究死亡组术后AKI分级为3级的较存活组多。

围术期高血糖是成人心脏病手术后死亡的危险因素[18-19],而高血糖对小儿先心病CPB手术预后影响的研究不多,且结果存在争议。Yates [20]认为血糖>6.5 mmol/L的持续天数影响婴儿先心病手术的存活率;而Agus [21]研究中并未发现术后3天严格控制血糖(4.4~6.1 mmol/L)对提高存活率有益处。Lou等[22]学者观察100例先心病婴儿CPB术中和术后血糖,发现平均血糖 < 8.3 mmol/L的并未比>8.3 mmol/L的存活率高。血糖水平升高引起心脏病术后预后不良的可能机制为:高血糖可通过caspase-3信号途径增加心肌细胞凋亡,激活JKA2途径使心肌细胞血管紧张素Ⅱ合成增加,外周血管阻力增加、心输出量和心指数降低;高血糖还可加重缺血细胞的酸中毒和水肿等[23-24]。本研究纳入的118例均为CPB术后48 h内发生AKI的患儿,存活组和死亡组术前血糖水平的差异无显著性,CPB术中两组血糖均有升高,但死亡组高于存活组,死亡率有随血糖升高而增加的趋势,而且术中血糖≤8.3 mmol/L的患儿平均生存期较长。提示CPB术中高血糖状态可促进AKI的发生或加重其严重程度。

综上所述,先天性心脏病CPB术后合并AKI患儿的术中血糖水平与预后相关,术中严格控制血糖上升对改善CPB术后AKI患儿的预后有积极作用。但本研究为回顾性研究,也未纳入术后心功能、术后液体超负荷等可能影响AKI或死亡率的其他因素;另外,不同年龄段或不同营养状态患儿的肌酐基础值不一致,采用术后48 h内的肌酐水平进行AKI的判断欠精准,因此仍需多中心大样本的前瞻性研究予以进一步认证。

| [1] |

Sanchez-de-Toledo J, Perez-Ortiz A, Gil L, et al. Early initiation of renal replacement therapy in pediatric heart surgery is associated with lower mortality[J]. Pediatr Cardiol, 2016, 37(4): 623-628. DOI:10.1007/s00246-015-1323-1 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Toda Y, Sugimoto K. AKI after pediatric cardiac surgery for congenital heart diseases-recent developments in diagnostic criteria and early diagnosis by biomarkers[J]. J Intensive Care, 2017(5): 49. (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Gist KM, Kaufman J, da Cruz EM, et al. A decline in intraoperative renal near-infrared spectroscopy is associated with adverse outcomes in children following cardiac surgery[J]. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2016, 17(4): 342-349. DOI:10.1097/PCC.0000000000000674 (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Park SK, Hur M, Kim E, et al. Risk factors for acute kidney injury after congenital cardiac surgery in infants and children:a retrospective observational study[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(11). (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Jetton JG, Rhone ET, Harer MW, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute kidney injury in pediatrics[J]. Curr Treat Options Pediatr, 2016, 2(2): 56-68. DOI:10.1007/s40746-016-0047-7 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Luo W, Zhu M, Huang R, et al. A comparison of cardiac post-conditioning and remote pre-conditioning in paediatric cardiac surgery[J]. Cardiol Young, 2011, 21(03): 266-270. DOI:10.1017/S1047951110001915 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Jenkins KJ, Kupiec JK, Owens PL. Development and validation of an agency for healthcare research and quality indicator for mortality after congenital heart surgery harmonized with risk adjustment for congenital heart surgery (RACHS-1) methodology[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2016, 5(5): e003028. DOI:10.1161/JAHA.115.003028 (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Pasquali SK, Hall M, Li JS, et al. Corticosteroids and outcome in children undergoing congenital heart surgery:analysis of the pediatric health information systems database[J]. Circulation, 2010, 122(21): 2123-2130. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.948737 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

骆德强, 陈自力, 戴巍, 等. 液体超负荷与婴儿先天性心脏病术后急性肾损伤的关系[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2017, 19(4): 376-380. DOI:10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2017.04.002 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Sathya B, Davis R, Taveira T, et al. Intensity of peri-operative glycemic control and postoperative outcomes in patients with diabetes:a meta-analysis[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2013, 102(1): 8-15. DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2013.05.003 (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Neff LP, Cannon JW, Morrison JJ, et al. Clearly defining pediatric massive transfusion:Cutting through the fog and friction with combat data[J]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2015, 78(1): 22-29. DOI:10.1097/TA.0000000000000488 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Tóth R, Breuer T, Cserép Z, et al. Acute kidney injury is associated with higher morbidity and resource utilization in pediatric patients undergoing heart surgery[J]. Ann Thorac Surg, 2012, 93(6): 1984-1990. DOI:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.10.046 (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Kumar TK, Allen Ccp J, Spentzas Md T, et al. Acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery in neonates and young infants:experience of a single center using novel perioperative strategies[J]. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg, 2016, 7(4): 460-466. DOI:10.1177/2150135116648305 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Aydin SI, Seiden HS, Blaufox AD, et al. Acute kidney injury after surgery for congenital heart disease[J]. Ann Thorac Surg, 2012, 94(5): 1589-1595. DOI:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.06.050 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Watkins SC, Williamson K, Davidson M, et al. Long-term mortality associated with acute kidney injury in children following congenital cardiac surgery[J]. Paediatr Anaesth, 2014, 24(9): 919-926. DOI:10.1111/pan.2014.24.issue-9 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Sanchez-de-Toledo J, Perez-Ortiz A, Gil L, et al. Early initiation of renal replacement therapy in pediatric heart surgery is associated with lower mortality[J]. Pediatr Cardiol, 2016, 37(4): 623-628. DOI:10.1007/s00246-015-1323-1 (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Bojan M, Gioanni S, Vouhé PR, et al. Early initiation of peritoneal dialysis in neonates and infants with acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery is associated with a significant decrease in mortality[J]. Kidney Int, 2012, 82(4): 474-481. DOI:10.1038/ki.2012.172 (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Greco G, Ferket BS, D'Alessandro DA, et al. Diabetes and the association of postoperative hyperglycemia with clinical and economic outcomes in cardiac surgery[J]. Diabetes Care, 2016, 39(3): 408-417. DOI:10.2337/dc15-1817 (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Giakoumidakis K, Nenekidis I, Brokalaki H. The correlation between peri-operative hyperglycemia and mortality in cardiac surgery patients:a systematic review[J]. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs, 2012, 11(1): 105-113. DOI:10.1177/1474515111430887 (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Yates A, Dyke PC 2nd, Taeed R, et al. Hyperglycemia is a marker for poor outcome in the postoperative pediatric cardiac patient[J]. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2006, 7(4): 351-355. DOI:10.1097/01.PCC.0000227755.96700.98 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Agus MS, Steil GM, Wypij D, et al. Tight glycemic control versus standard care after pediatric cardiac surgery[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 367(13): 1208-1219. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1206044 (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Song Lou, Fan Ding, Cun Long, et al. Effects of peri-operative glucose levels on adverse outcomes in infants receiving open-heart surgery for congenital heart disease with cardiopulmonary bypass[J]. Perfusion, 2011, 26(2): 133-139. DOI:10.1177/0267659110389843 (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Qiao Y, Zhao Y, Liu Y, et al. miR-483-3p regulates hyperglycaemia-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis in transgenic mice[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2016, 477(4): 541-547. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.06.051 (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Tsai KH, Wang WJ, Lin CW, et al. NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide anion-induced apoptosis is mediated via the JNK-dependent activation of NF-κB in cardiomyocytes exposed to high glucose[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2012, 227(4): 1347-1357. DOI:10.1002/jcp.22847 (  0) 0) |

2017, Vol. 19

2017, Vol. 19