2. 南方医科大学附属深圳市妇幼保健院 新生儿筛查中心, 广东 深圳 518028

无论是发展中国家还是发达国家,早产儿的营养和生长管理仍然是新生儿重症监护室(neonatal intensive care unit, NICU)的一个巨大挑战。脂肪乳提供了早产儿全静脉营养(total parentral nutrition, TPN)中25%~40%的非蛋白热卡[1]。早产儿早期应用脂肪乳的安全性已得到证实。通过监测血清甘油三酯及胆固醇浓度发现,早产儿可以耐受每日3 g/kg的脂肪乳[2-4]。但鲜有从代谢组学角度探讨早产儿脂肪乳的耐受性。营养指南推荐脂肪乳起始剂量为每日1 g/kg,每天可增加0.5~1.0 g/kg,至每日3.0 g/kg,但证据强度有待进一步提高[5]。而且早产儿的基础代谢能力及肝肾功能成熟程度与出生胎龄密切相关,因此不同胎龄早产儿使用脂肪乳的起始剂量、增加速度需要细化[6-7]。本研究通过了解不同出生胎龄早产儿生后早期短、中、长链酰基肉碱的浓度差异及相同胎龄段早产儿对不同剂量脂肪乳的代谢状态,探讨早产儿生后早期对脂肪乳的代谢特点,为早产儿生后早期更好地应用脂肪乳提供理论依据。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象选取2014年5~10月期间深圳市妇幼保健院新生儿重症监护室住院的早产儿98例为研究对象。纳入标准:本院产科出生(出生后即转入NICU),出生胎龄 < 37周,出生体重≤2 500 g。排除标准:足月儿,有严重先天畸形、遗传代谢病、围产期重度窒息(1 min、5 min Apgar评分均≤3分)及合并感染的早产儿;母亲为妊高症、妊娠期糖尿病或年龄 > 35周岁的早产儿。根据出生胎龄(gestational age, GA)分为超早产儿组(GA < 28周,n=17)、早期早产儿组(28周≤GA < 32周,n=48)和中晚期早产儿组(32周≤GA < 37周,n=33)[8];并根据脂肪乳剂量的高低,每组随机分为低剂量脂肪乳与高剂量脂肪乳两个亚组。

本研究获得医院伦理委员会批准及患儿家长知情同意。

1.2 资料收集收集患儿的一般资料,包括出生胎龄、出生体重、性别,以及生后前3天脂肪乳用量、生后第3天的肝、肾功能及脂代谢检查结果等。

1.3 营养支持方案所有早产儿均予以TPN,如胃肠道情况许可,可3 d内开始肠道内微量喂养(母乳或早产儿配方奶)。氨基酸(19AA-I,DCPC,中国)于生后2 h内开始使用,起始剂量为每日1.5~2.5 g/kg,每日增加0.5~1.0 g/kg,直至每日3.0~3.5 g/kg。20%中长链脂肪乳(C8-24,Baxter,中国)于生后12~24 h开始使用,低剂量脂肪乳组的起始剂量为每日0.5g/kg,第2天增加0.5 g/kg,第3天增加0.5~1.0 g/kg,至每日3.0~3.5 g/kg;高剂量脂肪乳组的起始剂量为每日1.0 g/kg,第2天增加0.5~1.0 g/kg,第3天增加1.0 g/kg,至每日3.0~3.5 g/kg。

1.4 血液酰基肉碱及肝肾功能、血脂检测所有入组早产儿均留取脐静脉血,及生后第1、2、3天留取血干滤纸,血斑直径≥ 8 mm,滤纸两面完全渗透,室温干透后置4℃冰箱保存待检。采用串联质谱仪(API3200型MS/MS;美国生物应用系统AB公司)进行血液酰基肉碱分析,包括游离肉碱、短、中、长链酰基肉碱等。

所有入组早产儿在出生后第3天常规采集静脉血检测肝、肾功能和血脂。

1.5 统计学分析采用SPSS 20.0统计学软件进行数据处理。正态分布的计量资料以均数±标准差(x±s)表示,多组间比较采用方差分析,两两比较采用SNK-q检验,相关性分析采用Pearson相关分析;计数资料采用百分率(%)表示,组间比较采用χ2检验。P < 0.05表示差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 临床特征分析超早产儿、早期早产儿和中晚期早产儿组出生胎龄、出生体重的差异均有统计学意义(P < 0.05);超早产儿组的男婴比例高于早期早产儿组及中晚期早产儿组(P < 0.05);超早产儿组与早期早产儿组的总胆固醇浓度均高于中晚期早产儿组(P < 0.05);3组的甘油三酯含量有随着胎龄增加而下降的趋势,但差异无统计学意义(P=0.83)。见表 1。

| 表 1 3组患儿的临床特征比较 |

2.2 血游离肉碱及短、中、长链酰基肉碱浓度的变化

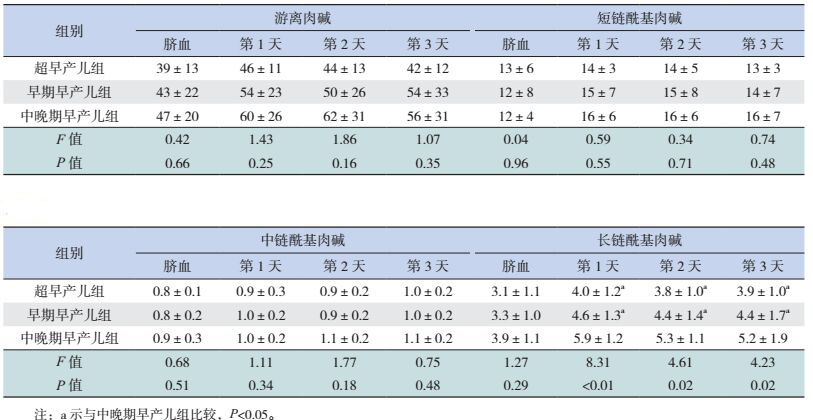

脐血和生后前3天的游离肉碱,以及短、中链酰基肉碱浓度在超早产儿、早期早产儿与中晚期早产儿3组间的差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05);脐血长链酰基肉碱浓度在3组患儿间的差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05),但出生后前3天的浓度随出生胎龄增加而增高(P < 0.05)。见表 2。出生后前3天的长链酰基肉碱浓度与出生胎龄成正相关,r值依次为0.49、0.36、0.31,P < 0.01。

| 表 2 3组患儿血游离肉碱及短、中、长链酰基肉碱浓度比较 (x±s,μmol/L) |

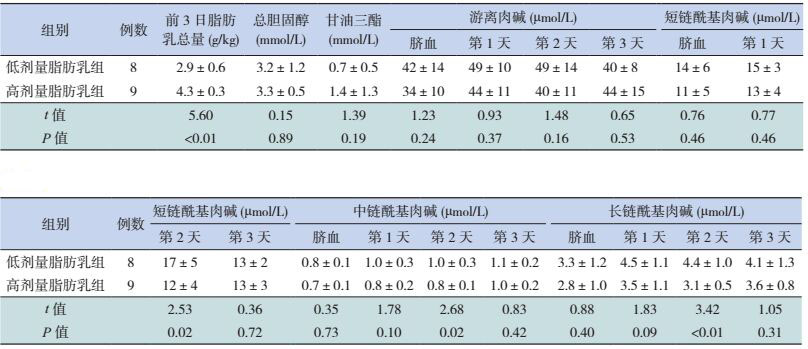

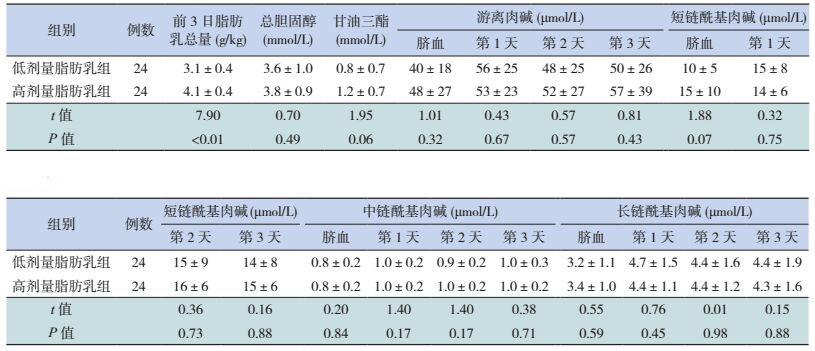

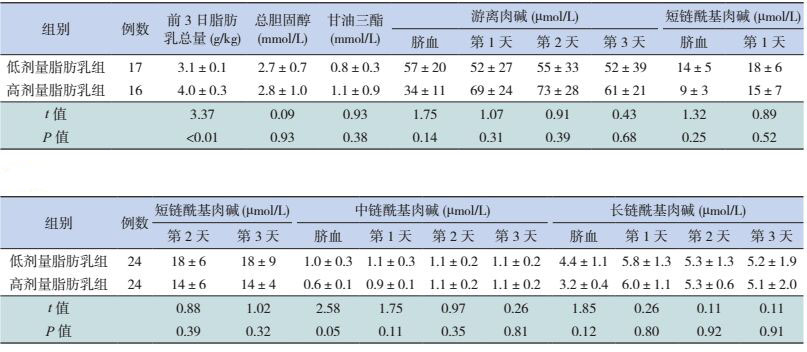

超早产儿低剂量脂肪乳组第2天的短、中、长链酰基肉碱浓度均高于高剂量组(P < 0.05);两个剂量组间的脐血、生后第1、3天的短、中、长链酰基肉碱浓度的差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。见表 3。早期早产儿与中晚期早产儿不同剂量脂肪乳组前3天的短、中、长链酰基肉碱浓度差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05),见表 4、5。超早产儿、早期早产儿与中晚期早产儿的低剂量组与高剂量组之间的总胆固醇、甘油三脂和游离肉碱浓度差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05),见表 3~5。

| 表 3 超早产儿不同剂量脂肪乳组的脂代谢及肉碱浓度比较 (x±s) |

| 表 4 早期早产儿不同剂量脂肪乳组的脂代谢及肉碱浓度比较 (x±s) |

| 表 5 中晚期早产儿不同剂量脂肪乳组脂代谢及肉碱浓度比较 (x±s) |

3 讨论

早产儿的营养和生长管理是NICU的一个巨大挑战。而早产儿由于机体的不成熟,生后早期往往不能得到充分的肠内喂养;而且生后一周内常出现严重的营养缺失,不仅可造成生长受限,并且对成年期也可能产生不良影响[9]。因此,静脉营养成了早产儿生后早期甚至较长一段时间的主要营养来源[9-10]。近年来,多数指南均推荐“积极营养”方案,即早产儿生后尽早进行肠外营养,第一天最低起始热卡为40 kcal/kg,氨基酸2~3 g/kg,脂肪乳1 g/kg,并在生后一周内达到每天热卡90~120 kcal/kg、氨基酸3.5 g/kg、脂肪乳3 g/kg。而TPN的具体实施,每个NICU之间的有很大区别[9-10]。有研究认为“积极营养”方案能减少早产儿宫外生长受限的发生率并改善其神经系统发育、认知等远期预后[11-12]。但也有研究者反对“积极营养”方案,认为可能造成营养素代谢的不耐受[13]。

早产儿对脂肪乳的耐受性主要是通过血清甘油三酯及胆固醇等生化指标来反映[2]。与传统生化指标相比,串联质谱法具有高灵敏性、高特异性、高选择性等优点,能直接对生物体内所有代谢物进行定量分析,能检测干血滤纸片中数十种氨基酸、游离肉碱及酰基肉碱,能分析包含2-C到20-C的饱和或不饱和酰基肉碱家族[14]。因此,本研究从代谢组学角度应用串联质谱法分析早产儿生后早期对脂肪乳的耐受性。

酰基肉碱是一种左旋肉碱脂肪酰酯,是脂肪酸在肉碱酰基转移酶的作用下游离肉碱酯酰化而成,并通过肉碱转运体不可逆地跨入细胞器膜进入线粒体或过氧化物酶,在肉碱酰基水解酶的作用下释放出游离肉碱,而水解的脂肪酰基将进行β-氧化[15]。肉碱棕榈酰转移酶Ⅰ(carnitine palmitoyl transferases Ⅰ, CPTI)是酰基肉碱转移酶家族中的第一个成员,将细胞质内的长链酰基辅酶A与游离肉碱结合,形成长链酰基肉碱;肉碱棕榈酰转移酶Ⅱ(carnitine palmitoyl transferases Ⅱ, CPTII)是第二个成员,位于线粒体内膜,在线粒体内将长链酰基肉碱转化成长链脂肪酸并释放出游离肉碱,长链脂肪酸由此进入β-氧化[17];肉碱乙酰基转移酶是第三个成员,特异性结合短链酰基群,将短链脂肪酸转化为短链酰基肉碱;肉碱辛基转移酶是肉碱转移酶家族中最后一个成员,只存在于过氧化物酶体,并且优先与中链酰基辅酶A结合[16]。

早产儿胎龄越小,器官发育越不成熟,相应的酰基肉碱转移酶活性也不足。本研究结果显示,各胎龄段早产儿的游离肉碱浓度差异虽无统计学意义,但胎龄越小,游离肉碱浓度越低。与Clark等[17]的研究类似。研究结果还显示,超早产儿组与早期早产儿组生后前3天的长链酰基肉碱浓度均低于中晚期早产儿组,且长链酰基肉碱浓度与出生胎龄成正相关。由此推测,超早产儿与早期早产儿对长链脂肪酸的代谢可能更容易受体内游离肉碱浓度及肉碱转移酶CPTI、CPTII活性的影响,使得长链脂肪酸与游离肉碱转化成长链酰基肉碱的能力不足。本研究结果还显示,超早产儿低剂量脂肪乳组生后第2天的短、中、长链酰基肉碱浓度均高于高剂量脂肪乳组,而早期早产儿与中晚期早产儿的不同剂量脂肪乳亚组间的短、中、长链酰基肉碱浓度的差异没有统计学意义。提示超早产儿可能在生后早期对高剂量脂肪乳的耐受性不足,因此在临床应用中,对脂肪乳的起始剂量、剂量的增加等需要慎重选择。

从代谢组学的角度发现,超早产儿和早期早产儿生后前三天对长链脂肪酸的代谢能力均低于中晚期早产儿;早期早产儿与中晚期早产儿生后早期可以耐受较高剂量的脂肪乳。

| [1] | Berthold K, Olivier G, Joanne H, et al. For the parenteral nutrition guidelines working group:guidelines on paediatric parenteral nutrition of the European society of paediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the European society for clinical nutrition and metabolism (ESPEN), supported by the European society of paediatric[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2005, 41 (Suppl 2): S1–S87. |

| [2] | Guellec I, Gascoin G, Beuchee A, et al. Biological impact of recent guidelines on parenteral nutrition in preterm infants[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2015, 61 (6): 605–609. DOI:10.1097/MPG.0000000000000898 |

| [3] | Vlaardingerbroek H, van Goudoever JB. Intravenous lipids in preterm infants:impact on laboratory and clinical outcomes and long-term consequences[J]. World Rev Nutr Diet, 2015, 112 : 71–80. |

| [4] | Kao LC, Cheng MH, Warburton D. Triglycerides, free fatty acids, free fatty acids/albumin molar ratio, and cholesterol levels in serum of neonates receiving long-term lipid infusions:controlled trial of continuous and intermittent regimens[J]. J Pediatr, 1984, 104 (3): 429–435. DOI:10.1016/S0022-3476(84)81111-7 |

| [5] | 中华医学会肠外肠内营养学分会儿科协作组, 中华医学会儿科学分会新生儿学组, 中华医学会小儿外科学分会新生儿学组. 中国新生儿营养支持临床应用指南[J]. 临床儿科杂志, 2013, 31 (12): 1177–1182. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3606.2013.12.020 |

| [6] | Hellgren G, Engström E, Smith LE, et al. Effect of preterm birth on postnatal apolipoprotein and adipocytokine profiles[J]. Neonatology, 2015, 108 (1): 16–22. DOI:10.1159/000381278 |

| [7] | Hay WW Jr, Brown LD, Denne SC. Energy requirements, protein-energy metabolism and balance, and carbohydrates in preterm infants[J]. World Rev Nutr Diet, 2014, 110 : 64–81. DOI:10.1159/000358459 |

| [8] | Hannah Blencowe, Simon Cousens, Doris Chou, et al. 15 million preterm births:priorities for action based on national, regional and global estimates[DB/OL]. (2012-05-12)[2017-01-19]. http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/news/2012/borntoosoon_chapter2.pdf. |

| [9] | Stephens BE, Walden RV, Gargus RA, et al. First-week protein and energy intakes are associated with 18-month developmental outcomes in extremely low birth weight infants[J]. Pediatrics, 2009, 123 (5): 1337–1343. DOI:10.1542/peds.2008-0211 |

| [10] | Senterre T, Terrin G, De Curtis M, et al. Parenteral nutrition in premature infants[M]//Guandalini S, Dhawan A, Branski D Cham. Textbook of pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition:a comprehensive guide to practice. Switzerland:Springer International Publishing, 2016:73-86. |

| [11] | Hay WW Jr. Aggressive nutrition of the preterm infant[J]. Curr Pediatr Rep, 2013, 1 (4). DOI:10.1007/s40124-013-0026-4 |

| [12] | Su BH. Optimizing nutrition in preterm infants[J]. Pediatr Neonat, 2014, 55 (1): 5–13. DOI:10.1016/j.pedneo.2013.07.003 |

| [13] | Aldana-Valenzuela C. Early aggressive nutrition in premature infants:is this the best approach[J]. J Pediatr Gastr Nutr, 2015, 61 (3): 269–270. DOI:10.1097/MPG.0000000000000894 |

| [14] | Chace DH, Kalas TA, Naylor EW. Use of tandem mass spectrometry for multianalyte screening of dried blood specimens from newborns[J]. Clin Chem, 2003, 49 (11): 1797–1817. DOI:10.1373/clinchem.2003.022178 |

| [15] | Borum PR. Carnitine homeostasis in humans[M]//Wall BT, Porter C. Carnitine metabolism and human nutrition. Newyork:CRC Press:Taylor & Francis Group, 2014:3-10. |

| [16] | Altamimi TR, Lopaschuk GD. Role of carnitine in modulation of muscle energy metabolism and insulin resistance[M]//Wall BT, Porter C. Carnitine metabolism and human nutrition. Newyork:CRC Press:Taylor & Francis Group, 2014:11-27. |

| [17] | Clark RH, Kelleher AS, Chace DH, et al. Gestational age and age at sampling influence metabolic profiles in premature infants[J]. Pediatrics, 2014, 134 (1): e37–e46. DOI:10.1542/peds.2014-0329 |

2017, Vol. 19

2017, Vol. 19