以地塞米松(dexamethasone, DEX)为代表的糖皮质激素(glucocorticoids, GCs)现广泛应用于妊娠34周前有早产危险的孕妇,以降低早产儿发生新生儿呼吸窘迫综合征的危险,同时GCs能有效减轻新生儿对氧的依赖,加快撤离呼吸机及缩短用氧时间[1-4]。然而有文献报道在围产期曾接受GCs治疗的儿童发生脑室周围白质软化、行为异常危险性明显增高,青春期运动和认知水平均落后[4-6]。鉴于围产期应用GCs对发育中脑存在潜在的长期不良影响,研究GCs对发育中脑的影响机制对合理应用GCs有重要意义。

神经元迁移是脑发育的重要阶段,而围产期是神经元迁移的关键时期,如果GCs干扰到该过程,将可能影响到脑发育及功能[7]。神经元迁移过程由复杂的分子网络所控制,在该网络中,神经元迁移蛋白Lissencephaly 1(LIS1)构成以其为核心的一个信号通路系统,参与脑发育。LIS1与doublecortin(DCX)和tubulin共同调控微管的组织和转运[8]。LIS1通过与磷酸化Nuclear distribution factor E-homolog like1蛋白结合,与胞浆中微管运动蛋白dynein和dynactin形成复合物,连接细胞骨架蛋白到放射性胶质细胞(RGCs)的细胞外基质,稳定RGCs之间细胞连接,维持放射性形态,控制细胞胞体转位、移行[9-10]。LIS1与磷酸化DCX结合,调节神经突起的延伸及神经元迁移,维持神经元移行过程的双极形态[11]。LIS1信号通路又与细胞存活、分裂、增殖及分化过程密切相关[12-14]。LIS1信号通路的关键基因发生突变或缺失将导致严重神经系统异常[15-23]。本研究拟通过对体外培养胎鼠皮层神经元细胞,应用皮质酮干预后研究神经元迁移蛋白LIS1表达的变化,以期揭示GCs对发育中神经细胞迁移可能的影响,从而进一步阐明GCs在发育中脑损伤过程中的作用机制。

1 材料与方法 1.1 大脑皮层神经元原代培养取妊娠16~17 d的Wistar大鼠(购自湖南斯莱克景达实验动物有限公司),无菌条件下剥离胎鼠脑组织,分离出大脑皮层,解剖显微镜下去除脑膜。胰蛋白酶消化后的组织置于含10%胎牛血清(FBS,杭州天杭生物科技股份有限公司)的DMEM中,制备细胞悬液,以5×105/mL细胞悬液接种至铺有多聚赖氨酸的培养瓶或培养皿中,置于5%CO2孵箱(湿度为100%),于37℃孵育。体外培养24~48 h后用10% FBS-DMEM全量换液,第5天使用含有10-5 mol/L阿糖胞苷的培养液培养,抑制胶质细胞生长,作用24 h后全量换出,继续10% FBS-DMEM培养,每3~4 d半量换液1次,体外培养7~9 d后进行不同干预。

1.2 实验分组依据皮质酮(美国Sigma公司)终浓度分设对照组、低浓度干预组与高浓度干预组,即对应皮质酮终浓度分别为0、0.1、1.0 μmol/L。干预组使用含有不同浓度皮质酮的10% FBS-DMEM培养7 d,之后全量换液为不含皮质酮的10% FBS-DMEM培养。分别于干预结束后1、4、7 d收集细胞。

1.3 MTT法测定代谢率依据1.1所述方法于96孔板中行胎鼠大脑皮层神经元原代培养,按不同的分组进行相应干预,对照组及各干预组干预后各时间点分别培养10孔原代细胞,干预结束后1、4、7 d移去培养液,用无菌PBS洗涤2次后,每孔内加入终浓度为0.5 g/L MTT(北京索莱宝科技有限公司)的DMEM 100 μL继续培养4 h,吸出培养液,每孔加入150 μL DMSO,置摇床上低速振荡10 min,使结晶物质充分溶解。酶标仪测定在490 nm处检测吸光度值(OD值)。

1.4 Western blot法检测LIS1蛋白的表达依据1.1所述方法于培养瓶中行胎鼠大脑皮层神经元原代培养,按不同的分组进行相应干预,对照组及各干预组干预后各时间点分别培养7瓶原代神经元细胞,干预结束后1、4、7 d移除培养液,用预冷的PBS冲洗3次。加入溶解缓冲液A1 [10 mmol/L Hepes(pH7.9),1.5 mmol/L MgCl2,10 mmol/L KCl,0.5 mmol/L DTT,0.2 mmol/L PMSF,0.06%NP-40],用细胞刮匙刮取细胞,收集于离心管中。冰上静置10 min,后4℃ 7 000 r/min离心10 min。收集上清液为胞浆蛋白溶液,-20℃保存备用。在沉淀中加入50 μL溶解缓冲液A2 [20 mmol/L Hepes(pH7.9),20%甘油,420 mmol/L NaCl,1.5 mmol/L MgCl2,0.5 mmol/L EDTA,1 mmol/L PMSF],冰上静置20 min,13 300 r/min离心20 min。收集含胞核蛋白上清液,-20℃保存备用。应用微量板全波段酶标仪采用紫外吸收法测定蛋白浓度。蛋白标本加入1/4体积的5×加样缓冲液[0.25 mol/L Tris-HCl(pH 6.8),10%十二烷基磺酸钠(SDS),0.005%溴酚蓝,50%甘油,5%β-巯基乙醇],采用10%SDS-聚丙烯凝胶电泳分离,每条泳道按20 μg/20 μL上样,其中旁边两孔加入蛋白marker标记。电泳结束后用半干法转蛋白至PVDF膜,于5%脱脂奶中封闭1 h。加一抗溶液[小鼠抗大鼠LIS1单克隆抗体(英国Abcam公司)1:500,内参为兔抗大鼠GAPDH多克隆抗体(美国Protein Tech公司)1:1 000] 4℃孵育过夜,用TTBS液洗膜后,加入辣根过氧化物酶标记的相应二抗(1:1 000山羊抗小鼠IgG,1:1 000山羊抗兔IgG,均购自美国Protein Tech公司)室温孵育2 h,TTBS充分洗膜后,暗室中曝光X光片。采用数字凝胶成像分析系统进行扫描,使用Image J系统分析条带灰度值,将目的蛋白灰度值与GAPDH蛋白灰度值的比值作为目的蛋白相对表达量。

1.5 免疫细胞化学方法检测LIS1蛋白的表达依前述方法行神经元培养及干预,在不同时间点制备神经元原代细胞爬片,各组不同时间点分别制备10张爬片,冰丙酮固定,0.5%Triton X-100孵育20 min,3%H2O2孵育15 min。小鼠抗大鼠LIS1单克隆抗体(1:500)4℃孵育过夜。辣根过氧化物酶标记山羊抗小鼠IgG抗体(1:1 000)室温孵育30 min。DAB显色法显色后树胶封片。在×400镜下取细胞分布均匀的视野进行观察。对所选区域运用Image-Pro Plus 6.0图像分析软件测定阳性反应细胞平均光密度值(average optical density value, AOD),代表目的蛋白表达水平。

1.6 统计学分析采用SPSS 18.0统计软件对数据进行统计学比较分析,计量资料以均数±标准差(x±s)表示,多组间均数比较采用单因素方差分析,组间两两比较采用SNK-q检验,P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

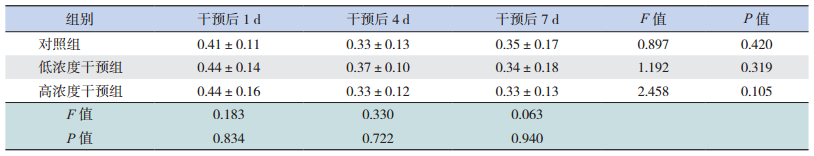

2 结果 2.1 皮质酮对体外培养胎鼠脑皮层神经元MTT代谢率的影响皮质酮干预后1、4、7 d,两干预组与对照组之间体外培养胎鼠脑皮层神经元MTT代谢率比较差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05),同时每组各时间点间MTT代谢率比较差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05),见表 1。

| 表 1 皮质酮干预后胎鼠脑皮层神经元MTT代谢率的变化 (x±s,n=10) |

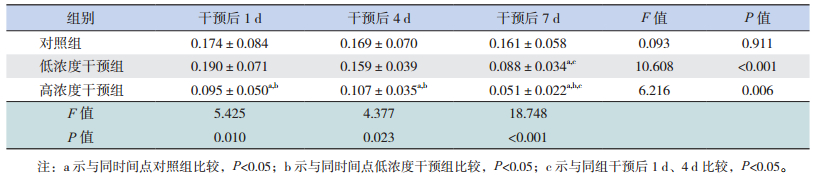

2.2 皮质酮干预对体外培养胎鼠脑皮层神经元LIS1表达的影响

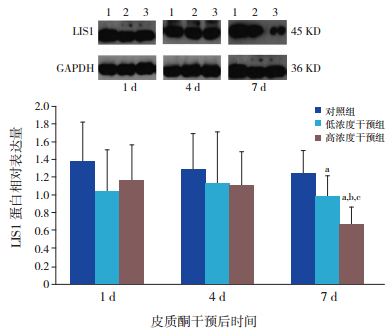

Western blot结果显示干预后1 d及4 d,各组胎鼠脑皮层神经元胞浆及胞核LIS1表达差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05);而干预后7 d,低浓度干预组、高浓度干预组胎鼠脑皮层神经元胞浆及胞核LIS1表达均明显低于相应对照组(P < 0.05),且在高浓度干预组胞浆中LIS1明显低于低浓度干预组(P < 0.05);各时间点低浓度干预组间胞浆及胞核内LIS1表达比较差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05),干预后7 d时,高浓度干预组胞浆及胞核内LIS1表达明显低于干预后1 d及4 d(P < 0.05)。见图 1~2。

|

图 1 Western blot检测皮质酮对胎鼠脑皮层神经元胞浆内LIS1蛋白变化的影响 上图为电泳条带图,1:对照组;2:低浓度干预组;3:高浓度干预组。下图为统计图(n=7)a示与同时间点对照组比较,P < 0.05;b示与同时间点低浓度干预组比较,P < 0.05;c示与同组干预后1 d、4 d比较,P < 0.05。 |

|

图 2 Western blot检测皮质酮对胎鼠脑皮层神经元胞核内LIS1蛋白变化的影响 上图为电泳条带图,1:对照组;2:低浓度干预组;3:高浓度干预组。下图为统计图(n=7)a示与同时间点对照组比较,P < 0.05;b示与同组干预后1 d、4 d比较,P < 0.05。 |

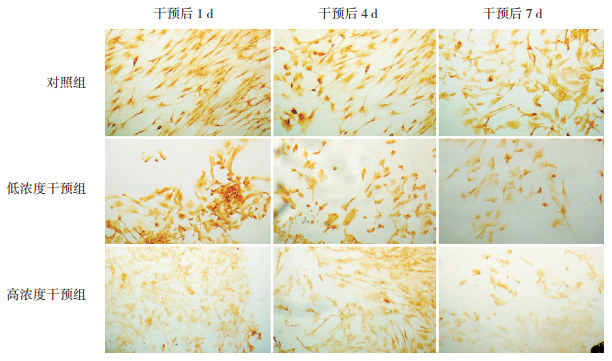

免疫细胞化学染色显示干预后1、4、7 d,高浓度干预组胎鼠脑皮层神经元LIS1 AOD值明显低于同时间点对照组及低浓度干预组(P < 0.05);且干预后7 d,低浓度干预组胎鼠脑皮层神经元LIS1 AOD值明显低于同时间点对照组(P < 0.05);干预后7 d,低浓度干预组胎鼠脑皮层神经元LIS1 AOD值明显低于干预后1 d及4 d(P < 0.05),高浓度干预组胎鼠脑皮层神经元LIS1 AOD值亦明显低于干预后1 d及4 d(P < 0.05)。见图 3,表 2。

|

图 3 皮质酮干预后1、4、7 d各组胎鼠脑皮层神经元LIS1表达改变(DAB染色,×200) 干预后1、4、7 d,高浓度干预组阳性细胞的强度低于相应对照组及低浓度干预组;干预后7 d,低浓度干预组阳性细胞的强度低于相应对照组;干预后7 d,低浓度干预组及高浓度干预组阳性细胞的强度低于干预后1 d及4 d;染色成棕黄色的细胞为阳性细胞。 |

| 表 2 皮质酮干预后各组胎鼠脑皮层神经元LIS1免疫细胞化学AOD值比较 (x±s,n=10) |

3 讨论

GC在体内的水平增高将对脑发育产生长远的影响。新生动物与母亲长期隔离导致慢性内源性GC增高,到成年期则出现行为异常[24]。而大鼠妊娠期给予DEX后,胎鼠脑内神经干细胞分裂停滞于G1期,向神经元定向分化受到干扰[25-26];新生大鼠应用DEX后,海马区及大脑皮层神经元细胞增殖减少,海马和胼胝体区星形胶质细胞的数目明显减少[27-32]。有研究显示如果GC长期高于生理水平,将诱导氧自由基产生,加重兴奋毒性神经损害,抑制神经元对糖的代谢[33-34],造成神经细胞损害。本实验中使用不同浓度皮质酮干预体外培养胎鼠脑皮层神经元,各时间点皮质酮干预组MTT代谢率比较差异无统计学意义,提示在一定浓度范围内,皮质酮对发育中胎鼠脑皮层神经元的线粒体能量代谢未造成显著影响,不支持GC通过影响神经元的能量代谢而影响发育中神经元。

Lis1作为第一种被克隆出的与神经元移行相关的基因,其蛋白产物LIS1构成以其为核心的一个信号通路系统,参与神经元迁移[8-11],又与细胞存活、增殖及分化密切相关[12-14]。Lis1基因正常表达是脑发育所必需的[35-37],该基因异常将导致包括平滑脑在内的严重神经系统畸形[15-23]。本研究显示LIS1蛋白作为重要的细胞骨架蛋白,在体外培养的胎鼠脑皮层神经元中,胞浆和胞核内均有表达,随着培养时间的延长,表达水平维持稳定。在皮质酮干预后7 d,通过Western blot和免疫细胞化学显示无论高浓度抑或低浓度皮质酮干预时,LIS1蛋白在胞浆和胞核中表达有显著下调,提示皮质酮影响神经元中LIS1表达,LIS1表达的下调可能影响神经元迁移的某一环节甚至多个环节,如果这种调节是病理性的,将导致部分神经元未能在正确的时间迁移至目的地,或是未能迁移至正确的目的地,影响神经功能网络的正确建立,最终发生脑功能障碍。下调LIS1的表达可能也参与神经细胞的分裂与增殖,有可能影响神经细胞数量,进一步影响脑发育。提示LIS1下调对神经细胞迁移的影响可能参与到GCs对脑发育及发育中脑损伤的过程中。

本研究同时显示无论高浓度,抑或低浓度皮质酮干预对LIS1表达的影响都非短期内出现,而在干预后7 d出现显著性减少。现今认为GCs可以通过与靶细胞的相关受体相结合后,转入细胞核内,结合到激素反应单元,调节靶基因表达[38]。推测GCs主要影响到Lis1基因的转录过程,非即刻快速机制影响LIS1表达,即便终止皮质酮干预后仍存在后续效应。在本实验中发现皮质酮对发育中胎鼠脑皮层神经元胞核内LIS1的影响并不比胞浆内明显,胞核内LIS1仅在高浓度长期作用后出现表达下降的改变,这进一步提示了胞浆及胞核内LIS1表达的不同步性,这也提示了皮质酮对LIS1的转录、翻译、转运、分布产生了“空间性”、“区域性”的影响。在本实验中发现高浓度皮质酮干预后7 d,胞浆及胞核内LIS1表达均明显低于干预后1 d、4 d,这提示皮质酮对胞浆及胞核内LIS1表达的影响也具有剂量依赖性,浓度越高,LIS1表达下调越明显。因此在临床中应避免长时间、高浓度的使用GC,以保护脑的发育。

总之,皮质酮可能通过影响发育中胎鼠脑皮层神经元神经迁移蛋白LIS1表达而导致发育中脑损伤,这种影响同剂量的高低、作用时间的长短有关。

| [1] | Sweet DG, Carnielli V, Greisen G, et al. European consensus guidelines on the management of respiratory distress syndrome-2016 update[J]. Neonatology, 2017, 111 (2): 107–125. DOI:10.1159/000448985 |

| [2] | Doyle LW, Ehrenkranz RA, Halliday HL. Early (< 8 days) postnatal corticosteroids for preventing chronic lung disease in preterm infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2014 (5): CD001146. |

| [3] | Onland W, Offringa M, van Kaam A. Late (≥ 7 days) inhalation corticosteroids to reduce bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012 (4): CD002311. |

| [4] | Doyle LW, Ehrenkranz RA, Halliday HL. Dexamethasone treatment after the first week of life for bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants:a systematic review[J]. Neonatology, 2010, 98 (4): 289–296. DOI:10.1159/000286212 |

| [5] | ter Wolbeek M, de Sonneville LM, de Vries WB, et al. Early life intervention with glucocorticoids has negative effects on motor development and neuropsychological function in 14-17 year-old adolescents[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2013, 38 (7): 975–986. DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.10.001 |

| [6] | Cheong JL, Burnett AC, Lee KJ, et al. Association between postnatal dexamethasone for treatment of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and brain volumes at adolescence in infants born very preterm[J]. J Pediatr, 2014, 164 (4): 737–743. DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.083 |

| [7] | Solecki DJ. Sticky situations:recent advances in control of cell adhesion during neuronal migration[J]. Curr Opin Neurobiol, 2012, 22 (5): 791–798. DOI:10.1016/j.conb.2012.04.010 |

| [8] | Moon HM, Wynshaw-Boris A. Cytoskeleton in action:lissencephaly, a neuronal migration disorder[J]. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol, 2013, 2 (2): 229–245. DOI:10.1002/wdev.v2.2 |

| [9] | Clark GD. Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase and brain development[J]. Enzymes, 2015, 38 : 37–42. DOI:10.1016/bs.enz.2015.09.009 |

| [10] | Pandey JP, Smith DS. A Cdk5-dependent switch regulates Lis1/Ndel1/dynein-driven organelle transport in adult axons[J]. J Neurosci, 2011, 31 (47): 17207–17219. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4108-11.2011 |

| [11] | Nishimura YV, Shikanai M, Hoshino M, et al. Cdk5 and its substrates, Dcx and p27kip1, regulate cytoplasmic dilation formation and nuclear elongation in migrating neurons[J]. Development, 2014, 141 (18): 3540–3550. DOI:10.1242/dev.111294 |

| [12] | Chen X, Zhang J, Zhao J, et al. Lis1 is required for the expansion of hematopoietic stem cells in the fetal liver[J]. Cell Res, 2014, 24 (8): 1013–1016. DOI:10.1038/cr.2014.69 |

| [13] | Zimdahl B, Ito T, Blevins A, et al. Lis1 regulates asymmetric division in hematopoietic stem cells and in leukemia[J]. Nat Genet, 2014, 46 (3): 245–252. DOI:10.1038/ng.2889 |

| [14] | Lanctot AA, Peng CY, Pawlisz AS, et al. Spatially dependent dynamic MAPK modulation by the Nde1-Lis1-Brap complex patterns mammalian CNS[J]. Dev Cell, 2013, 25 (3): 241–255. DOI:10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.006 |

| [15] | Bahi-Buisson N, Guerrini R. Diffuse malformations of cortical development[J]. Handb Clin Neurol, 2013, 111 : 653–665. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-444-52891-9.00068-3 |

| [16] | Fry AE, Cushion TD, Pilz DT. The genetics of lissencephaly[J]. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet, 2014, 166C (2): 198–210. |

| [17] | Liu JS. Molecular genetics of neuronal migration disorders[J]. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep, 2011, 11 (2): 171–178. DOI:10.1007/s11910-010-0176-5 |

| [18] | Pawlisz AS, Feng Y. Three-dimensional regulation of radial glial functions by Lis1-Nde1 and dystrophin glycoprotein complexes[J]. PLoS Biol, 2011, 9 (10): e1001172. DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001172 |

| [19] | Moon HM, Youn YH, Pemble H, et al. LIS1 controls mitosis and mitotic spindle organization via the LIS1-NDEL1-dynein complex[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2014, 23 (2): 449–466. DOI:10.1093/hmg/ddt436 |

| [20] | Sebe JY, Bershteyn M, Hirotsune S, et al. ALLN rescues an in vitro excitatory synaptic transmission deficit in Lis1 mutant mice[J]. J Neurophysiol, 2013, 109 (2): 429–436. DOI:10.1152/jn.00431.2012 |

| [21] | Garcia-Lopez R, Pombero A, Dominguez E, et al. Developmental alterations of the septohippocampal cholinergic projection in a lissencephalic mouse model[J]. Exp Neurol, 2015, 271 : 215–227. DOI:10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.06.014 |

| [22] | Moore KD, Chen R, Cilluffo M, et al. Lis1 reduction causes tangential migratory errors in mouse spinal cord[J]. J Comp Neurol, 2012, 520 (6): 1198–1211. DOI:10.1002/cne.v520.6 |

| [23] | Lockrow JP, Holden KR, Dwivedi A, et al. LIS1 duplication:expanding the phenotype[J]. J Child Neurol, 2012, 27 (6): 791–795. DOI:10.1177/0883073811425972 |

| [24] | Arabadzisz D, Diaz-Heitjz R, Knuesel I, et al. Primate early life stress leads to long-term mild hippocampal decreases in corticosteroid receptor expression[J]. Biol Psychiatry, 2010, 67 (11): 1106–1109. DOI:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.016 |

| [25] | Moors M, Bose R, Johansson-Haque K, et al. Dickkopf 1 mediates glucocorticoid-induced changes in human neural progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation[J]. Toxicol Sci, 2012, 125 (2): 488–495. DOI:10.1093/toxsci/kfr304 |

| [26] | Mutsaers HA, Tofighi R. Dexamethasone enhances oxidative stress-induced cell death in murine neural stem cells[J]. Neurotox Res, 2012, 22 (2): 127–137. DOI:10.1007/s12640-012-9308-9 |

| [27] | Malaeb SN, Stonestreet BS. Postnatal glucocorticoid-induced hypomyelination, gliosis, and neurologic deficits are dose-dependent, preparation-specific, and reversible[J]. Exp Neurol, 2016, 278 : 1–3. DOI:10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.01.012 |

| [28] | Claessens SE, Belanoff JK, Kanatsou S, et al. Acute effects of neonatal dexamethasone treatment on proliferation and astrocyte immunoreactivity in hippocampus and corpus callosum:towards a rescue strategy[J]. Brain Res, 2012, 1482 : 1–12. DOI:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.08.017 |

| [29] | Oliveira M, Rodrigues AJ, Leão P, et al. The bed nucleus of stria terminalis and the amygdala as targets of antenatal glucocorticoids:implications for fear and anxiety responses[J]. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2012, 220 (3): 443–453. DOI:10.1007/s00213-011-2494-y |

| [30] | Ko MC, Hung YH, Ho PY, et al. Neonatal glucocorticoid treatment increased depression-like behaviour in adult rats[J]. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol, 2014, 17 (12): 1995–2004. DOI:10.1017/S1461145714000868 |

| [31] | Tijsseling D, Camm EJ, Richter HG, et al. Statins prevent adverse effects of postnatal glucocorticoid therapy on the developing brain in rats[J]. Pediatr Res, 2013, 74 (6): 639–645. DOI:10.1038/pr.2013.152 |

| [32] | Bhatt AJ, Feng Y, Wang J, et al. Dexamethasone induces apoptosis of progenitor cells in the subventricular zone and dentate gyrus of developing rat brain[J]. J Neurosci Res, 2013, 91 (9): 1191–1202. DOI:10.1002/jnr.v91.9 |

| [33] | Tijsseling D, Camm EJ, Richter HG, et al. Statins prevent adverse effects of postnatal glucocorticoid therapy on the developing brain in rats[J]. Pediatr Res, 2013, 74 (6): 639–645. DOI:10.1038/pr.2013.152 |

| [34] | Caffino L, Calabrese F, Giannotti G, et al. Stress rapidly dysregulates the glutamatergic synapse in the prefrontal cortex of cocaine-withdrawn adolescent rats[J]. Addict Biol, 2015, 20 (1): 158–169. DOI:10.1111/adb.2015.20.issue-1 |

| [35] | Pagnamenta AT, Lise S, Harrison V, et al. Exome sequencing can detect pathogenic mosaic mutations present at low allele frequencies[J]. J Hum Genet, 2012, 57 (1): 70–72. DOI:10.1038/jhg.2011.128 |

| [36] | Classen S, Goecke T, Drechsler M, et al. A novel inverted 17p13.3 microduplication disrupting PAFAH1B1(LIS1) in a girl with syndromic lissencephaly[J]. Am J Med Genet A, 2016, 161A (6): 1453–1458. |

| [37] | Lockrow JP, Holden KR, Dwivedi A, et al. LIS1 duplication:expanding the phenotype[J]. J Child Neurol, 2012, 27 (6): 791–795. DOI:10.1177/0883073811425972 |

| [38] | Nishi M, Kawata M. Dynamics of glucocorticoid receptor and mineralocorticoid receptor:implications from live cell imaging studies[J]. Neuroendocrinology, 2007, 85 (3): 186–192. DOI:10.1159/000101917 |

2017, Vol. 19

2017, Vol. 19