2. Maternal-Infant Care Research Centre, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto;

3. Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon)

There is good evidence demonstrating that neonates in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) experience pain, and surgical procedures without analgesia has adverse effects on long-term psychosocial development[1-2]. However, controversy remains in two areas: when it comes to determining whether mechanical ventilation leads to pain in neonates and what impacts (positive or negative) sedatives/analgesics have when used for the mechanically ventilated neonate[3-4].

Opioids are the most commonly used medication in the NICU for ventilator related discomfort/stress/pain. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of pain management from opioids during MV in neonates reports the outcome as underwhelming[5]. In the subgroup of very preterm infants born at <32 weeks of gestational age (GA) hypotension and a longer time to reach full enteral feeds were present in the morphine group compared to placebo. Therefore in the absence of significant clinical benefit and the potential for increased adverse effects routine use opioids in ventilated neonates is not advised and opioid use should be reserved for circumstances when clinical signs of pain are present[5].

Benzodiazepines, primarily midazolam, are the second most common medication studied in mechanically ventilated neonates, although there is a paucity of randomized controlled trials examining the use of benzodiazepines for this purpose. A meta-analysis of sedation with midazolam in neonates found insufficient evidence to recommend use and raised safety concerns, particularly neurological side effects[4, 6-8]. Although there are a handful of other sedative/analgesics used for sedation/analgesia in ventilated neonates including phenobarbital, chloral hydrate, ketamine and propofol, none of these medications have been evaluated specifically for sedation and/or pain relief in mechanically ventilated neonates.

The objective of this study was to investigate the trends in sedative and narcotic use during mechanical ventilation in Canadian NICUs from 2004 through 2009. We selected this time period mainly because there was uniform data during that time frame and the methods of data collection were significantly altered after 2010.

MethodsThis observational study examined data from infants born at <35 weeks of GA admitted to the NICUs contributing data to the Canadian Neonatal Network (CNN) during 2004-2009. The CNN maintains a national database from 30 hospitals with coverage of greater than 90% of the tertiary NICU beds in Canada. At each participating site, trained abstractors collect chart data from all NICU admissions according to common guidelines. Details of data collection and data management have been published elsewhere[9].

Infants were excluded if born with major congenital anomalies, deemed moribund, required pain management for surgical procedures (excluding laser eye surgery), had necrotizing enterocolitis or presence of a chest drain, had seizures and had a history of maternal narcotic abuse.

Study subjects included remaining infants who received invasive ventilation for greater than 24 hours. Eligible infants were categorized according to whether they received sedatives, narcotics, both or neither for greater than 24 hours consecutive hours during mechanical ventilation. The combined simultaneous exposure to narcotics/sedatives and mechanical ventilation for >24 hours was used as the calculated variable for use of narcotics and/or sedatives for mechanical ventilation since no independent variable exists in the CNN database. Narcotics included in the database are morphine, fentanyl, methadone, sufentanyl, meperidine, alfentynl and codeine. Sedatives included in the database are chloral hydrate, midazolam, lorazepam, phenobarbital, pentobarbital, ketamine and propofol.

Study variables were defined according to the Canadian Neonatal Network manual[10]. GA was defined as the best estimate based on early prenatal ultrasound, obstetric examination and obstetric history followed by pediatric estimate in that order unless postnatal pediatric estimate of gestation differed from the obstetric estimate by greater than 2 weeks. In that case, the pediatric estimate was used.

Temporal trends regarding use of sedatives and narcotics during ventilation was analyzed using the Cohrane-Armitage Trend Test separately for infants born at less than 29 weeks and infants born at 29 to 34 weeks of GA. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary NC) and statistical significance was evaluated using two-sided P values at the 5% testing level.

ResultsA total of 12 415 infants less than 35 weeks of GA were admitted to participating NICUs required invasive mechanical ventilation for great than 24 hours from 2004 to 2009. Of this population 5 002 infants were excluded base on exclusion criteria of this study, leaving 7 413 infants eligible for analysis of narcotics or sedative exposure during mechanical ventilation. There were 1 775 mechanically ventilated infants excluded from the cohort because they received narcotics or sedative for less than 24 hours. The final cohort included 5 638 infants; 897 (15.9%) infants received sedatives and 2 169 (38.5%) infants received narcotics. There were 722 (12.8%) infants in the cohort who received both narcotics and sedatives.

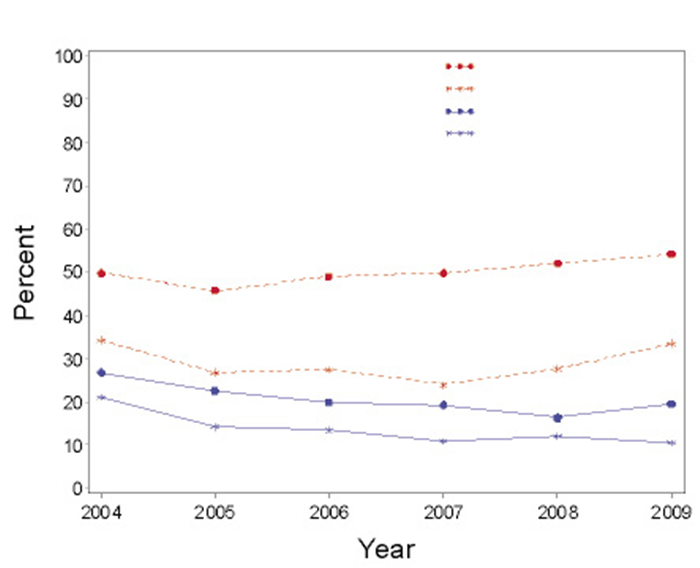

For infants less than 35 weeks of GA from 2004 to 2009, it was found there was no trend in narcotics use (P=0.11) and a decreased trend in sedative use (P<0.01). The trend in decreased sedative use was maintained for subgroup analysis by less than 29 weeks and 29-34 weeks of GA. For narcotics use the absence of trend was maintained in the subgroup 29-34 weeks of GA. However, for the subgroup of less than 29 weeks a significant trend towards increased utilization was identified (P=0.03) (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Trends in narcotics and sedatives usage during mechanical ventilation |

For infants receiving narcotics during mechanical ventilation the most frequently utilized pharmaceuticals were fentynl (63.8%) and morphine (62.2%), while meperidine and codeine were less used (0.3% and 0.1% respectively). For infants receiving sedatives, the utilized pharmaceuticals included phentobarbitol (44.9%), chloral hydrate (44.2%), midazolam (37.9%), lorazepam (12.9%), ketamine (1.4%), and propofol (0.2%).

DiscussionIs invasive mechanical ventilation painful and/or stressful on neonates? Adult studies tell us that about 25% of ICU patients remember their stay in ICUs and found intubation and ventilation distressing[11]. However, it is difficult to differentiate distress of ventilation from the distress of being in ICUs and other components of care. Ill preterm infants have high cortisol levels, although it is difficult to differentiate if this due to the severity of illness or distress/stress/pain from ventilation or both[12]. Literature evaluating the use of narcotics or sedatives during mechanical ventilation have failed to produce evidence of clinically significant reduction in pain and has raised concerns for adverse effects[3-4]. However the practice of using narcotics and sedatives during mechanical ventilation is common in the NICU. In this study across participating NICUs in Canada 54% of mechanically ventilated infants received narcotics and/or sedatives for greater than 24 hours.

Sedatives were utilized less commonly during mechanical ventilation compared to narcotics and we observed a decreased trend in sedative use over time. Concerns from the literature of inadvertent harm from sedatives may have had an influence on clinical practice in Canada. As the most studied sedative in this population we hypothesized that benzodiazepines would be the most commonly used sedatives; 37.9% of infants on sedatives received midazolam and 12.9% received lorazepam. However, the highest sedatives utilized in this cohort were phenobarbital (44.9%) and chloral hydrate (44.2%). There are no evidence-based trials describing the use of these pharmaceuticals for sedation in mechanical ventilation in neonates. Chloral hydrate has been primarily described for use in non-painful procedural sedation such as radiological procedures[13]. Historically chloral hydrate had been used frequently as a sedative-hypnotic for infants 'fighting the ventilator'[14]. Chloral hydrate is converted to tricholoroethanol, which is also metabolically active[15]. There has been a case report of encephalopathy from chloral hydrate in a neonate resulting from high concentrations of tricholoroethanol[16]. Therefore it is recommended that this pharmaceutical be used with caution in neonates[12]. Phenobarbital is the preferred therapy for seizure control in neonates and has been used in combination with opioids for reducing excitability in neonatal abstinence syndrome[17]. Antenatal and postnatal phenobarbital was previously thought to protect against intraventricular hemorrhage, however Cochrane reviews do not support these hypothesis[18-19]. In addition postnatal phenobarbital in these studies lead to prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation[19]. It is possible that some of the decreased trend observed in this analysis is secondary to a decrease in use of postnatal phenobarbital to prevent intraventricular hemorrhage. Studies in developing animals have raised serious concerns about neuronal apoptosis with phenobarbital[20]. Phenobarbital reduces the power of spontaneous activity transients (SATs) in the preterm brain encephalogram; SATs are important in preterm brain growth[21-22].

The literature does not support routine preemptive use of narcotics in the management of ventilated preterm infants[17]. Despite a lack of evidence of benefit and potential harm there has not been a substantive decrease in the use of narcotics during mechanical ventilation. Over the six year period of time 28% infants 29-34 weeks of GA in this cohort received narcotics. For infants less than 29 weeks there was a significant trend towards increase use of narcotics with 54% of infants receiving them. The difference between GA may partially be explained by the argument that extremely preterm infants are exposed to a higher number of stressful and painful procedures during their stay in NICUs and therefore require more analgesia[23]. However, we are unable to further elaborate on this hypothesis with our study design. Preemptive use of morphine in very preterm infants during mechanical ventilation is associated with hypotension and longer duration to establish full enteral feeds[24]. Studies evaluating the long-term neurodevelopmental impact of narcotics use are conflicting and complicated by factors such as off label morphine exposures and a variety of dosing regimens[25-28]. Fentanyl was the most commonly utilized narcotics in this cohort of mechanically ventilated infants (63.8%), closely followed by morphine (62.2%). The high representation of fentanyl in our analysis may be secondary to its common use in protocols for rapid sequence intubation for neonates[29].

The main strengths of our study include the large sample size of infants from a national cohort, which has valid and reliable methods of data collection. The main weakness of our study is that the database does have a specific variable to represent that mechanical ventilation was the indication for sedative or narcotics use. Therefore a variable was extrapolated from existing data. Since the main outcome was to compare the trend overtime any bias as a result of this limitation should be equally distributed. Utilization of a surrogate measure could have implications for overestimating or underestimating the use of narcotics/sedatives during mechanical ventilation in Canadian NICUs. Several variables such as severity of illness, duration of ventilation, indication for medications and pain/sedation scale data are lacking to further explore explanations for the trends observed in narcotics and sedative use during mechanical ventilation. Our data does not capture any environmental or non-pharmacological interventions aimed at reducing discomfort/stress/pain during mechanical ventilation. A change in the data variables collected for sedatives and narcotics from 2010 onwards, prevents us from reliably analyzing the trend of narcotics/sedatives use during mechanical ventilation beyond 2009 hence the limitation of the study period until 2010.

Recent evidence may have contributed to a decreased trend in sedative use during mechanical ventilation and studies are under way to answer this question. It is of concern that the population reported to be at the highest risk of adverse side effects from opioids during mechanical ventilation, are more likely to be receiving them. Untreated pain and stress in the NICU environment has short and long-term consequences; however narcotics and sedatives used to manage pain and stress are not without consequences to short and long-term development. Therefore it is essential to implement use of validated pain and sedation scales to assess pain/stress and nursing driven comfort protocols in mechanically ventilated neonates along with development of evidence based policies/guidelines for patient management including narcotics and sedative use[30]. Concern has been raised for the continuing use of narcotics, sedative and paralytics in ventilated preterm infants by neonatologists in spite of mounting negative evidence[31]. The utilization of non-pharmacological measures is vastly under studied in mechanically ventilated neonates and therefore it remains a potentially under utilized resource to decrease neonatal discomfort/stress/pain. Ongoing research into pharmaceuticals to moderate pain/stress for neonates during mechanical ventilation while limiting harmful effects and considering long-term outcomes is warranted. Chronic pain is an emerging field in neonatal patients and requires ongoing investigation.

In conclusion, sedative use in ventilated PTI in Canadian NICUs appears to be following the evidence and trending downwards, however a high exposure to phenobarbitol and chloral hydrate are described. On the other hand narcotics use has not changed in PTI born at 29 to 34 weeks of GA and increased in the extremely low GA group (less than 29 weeks) suggesting neonatologists in Canada were selective in their application of evidence based practice when it comes to narcotics and sedative use in their respective units[32]. It would be interesting to explore further the reasons why.

| [1] |

Anand KJ. Neonatal stress response to anesthesia and surgery[J]. Clin Perinatol, 1990, 17(1): 207-214. (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Surgery, Canadian Paediatric Society Fetus and Newborn Committee, et al. Prevention and management of pain in the neonate:an update[J]. Pediatrics, 2006, 118(5): 2231-2241. DOI:10.1542/peds.2006-2277 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Bellù R, de Waal KA, Zanini R. Opioids for neonates receiving mechanical ventilation[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2008(1): CD004212. (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Ng E, Taddio A, Ohlsson A. Intravenous midazolam infusion for sedation of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012(6): CD002052. (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Bellù R, de Waal K, Zanini R. Opioids for neonates receiving mechanical ventilation:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2010, 95(4): F241-F251. DOI:10.1136/adc.2008.150318 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Anand KJ, Barton BA, McIntosh N, et al. Analgesia and sedation in preterm neonates who require ventilatory support:results from the NOPAIN trial. Neonatal outcome and prolonged analgesia in neonates[J]. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 1999, 153(4): 331-338. (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Harte GJ, Gray PH, Lee TC, et al. Haemodynamic responses and population pharmacokinetics of midazolam following administration to ventilated, preterm neonates[J]. J Paediatr Child Health, 1997, 33(4): 335-338. DOI:10.1111/j.1440-1754.1997.tb01611.x (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

van Straaten HL, Rademaker CM, de Vries LS. Comparison of the effect of midazolam or vecuronium on blood pressure and cerebral blood flow velocity in the premature newborn[J]. Dev Pharmacol Ther, 1992, 19(4): 191-195. DOI:10.1159/000457484 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Lee SK, McMillan DD, Oholsson A, et al. Variations in practice and outcomes in the Canadian NICU network:1996-1997[J]. Pediatrics, 2000, 106(5): 1070-1079. DOI:10.1542/peds.106.5.1070 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Canadian Neonatal Network (CNN). Abstractor's Manual[S/OL]. [May 20, 2017]. http://www.canadianneonatalnetwork.org/portal/.2011.

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Granja C, Lopes A, Moreira S, et al. Patients' recollections of experiences in the intensive care unit may affect their quality of life[J]. Crit Care, 2005, 9(2): R96-R109. DOI:10.1186/cc3026 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Hughes D, Murphy JF, Dyas J, et al. Blood spot glucocorticoid concentrations in ill preterm infants[J]. Arch Dis Child, 1987, 62(10): 1014-1018. DOI:10.1136/adc.62.10.1014 (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Anand KJ, Hall RW. Pharmacological therapy for analgesia and sedation in the newborn[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2006, 91(6): F448-F453. DOI:10.1136/adc.2005.082263 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Knight M. Adverse drug reactions in neonates[J]. J Clin Pharmacol, 1994, 34(2): 128-135. DOI:10.1002/jcph.1994.34.issue-2 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Mayers DJ, Hindmarsh KW, Gorecki DK, et al. Sedative/hypnotic effects of chloral hydrate in the neonate:trichloroethanol or parent drug?[J]. Dev Pharmacol Ther, 1992, 19(2-3): 141-146. DOI:10.1159/000457475 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Laptook AR, Rosenfeld CR. Chloral hydrate toxicity in a preterm infant[J]. Pediatr Pharmacol (New York), 1984, 4(3): 161-165. (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Hall RW, Anand KJ. Pain management in newborns[J]. Clin Perinatol, 2014, 41(4): 895-924. DOI:10.1016/j.clp.2014.08.010 (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Shankaran S, Cepeda EE, Ilagan N, et al. Antenatal phenobarbital for the prevention of neonatal intracerebral hemorrhange[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1986, 154(1): 53-57. DOI:10.1016/0002-9378(86)90392-3 (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Smit E, Odd D, Whitelaw A. Postnatal phenobarbital for the prevention of intraventricular haemorrhage in preterm infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2013(8): CD001691. (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Loepke AW. Developmental neurotoxicity of sedatives and anesthetics:a concern for neonatal and pediatric critical care medicine?[J]. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2010, 11(2): 217-226. DOI:10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b80383 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Kaija M, Metsarnta M, Vanhatalo S. Drug effects on endogenous brain activity in preterm babies[J]. Brain Dev, 2014, 36(2): 116-123. DOI:10.1016/j.braindev.2013.01.009 (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Benders MJ, Palmu K, Menache C, et al. Early brain activity relates to subsequent brain growth in premature infants[J]. Cereb Cortex, 2015, 25(9): 3014-3024. DOI:10.1093/cercor/bhu097 (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Shah PS, Dunn M, Lee SK, et al. Early opioid infusion and neonatal outcomes in preterm neonates ≤ 28 weeks' gestation[J]. Am J Perinatol, 2011, 28(5): 361-366. DOI:10.1055/s-0030-1270112 (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Hall RW, Kronsberg SS, Barton BA, et al. Morphine, hypotension, and adverse outcomes among preterm neonates:who's to blame? Secondary results from the NEOPAIN trial[J]. Pediatrics, 2005, 115(5): 1351-1359. DOI:10.1542/peds.2004-1398 (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Ferguson SA, Ward WL, Paule MG, et al. A pilot study of preemptive morphine analgesia in preterm neonates:effects on head circumference, social behavior, and response latencies in early childhood[J]. Neurotoxicol Teratol, 2012, 34(1): 47-55. DOI:10.1016/j.ntt.2011.10.008 (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

MacGregor R, Evans D, Sugden D, et al. Outcome at 5-6 years of prematurely born children who received morphine as neonates[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 1998, 79(1): F40-F43. DOI:10.1136/fn.79.1.F40 (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Zwicker JG, Miller SP, Grunau RE, et al. Smaller cerebellar growth and poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes in very preterm infants exposed to neonatal morphine[J]. J Pediatr, 2016, 172: 81-87. DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.12.024 (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Steinhorn R, McPherson C, Anderson PJ, et al. Neonatal morphine exposure in very preterm infants-cerebral development and outcomes[J]. J Pediatr, 2015, 166(5): 1200-1207. DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.02.012 (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Barrington K. Premedication for endotracheal intubation in the newborn infant[J]. Paediatr Child Health, 2011, 16(3): 159-171. DOI:10.1093/pch/16.3.159 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Fleishman R, Zhou C, Gleason C, et al. Standardizing morphine use for ventilated preterm neonates with a nursing-driven comfort protocol[J]. J Perinatol, 2015, 35(1): 46-51. DOI:10.1038/jp.2014.131 (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Zimmerman KO, Smith PB, Benjamin DK, et al. Sedation, analgesia, and paralytics during mechanical ventilation of premature infants[J]. J Pediatr, 2017, 180: 99-104. DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.07.001 (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

McPherson C. Sedation and analgesia in mechanically ventilated preterm neonates:continue standard of care or experiment?[J]. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther, 2012, 17(4): 351-364. (  0) 0) |

2018, Vol. 20

2018, Vol. 20