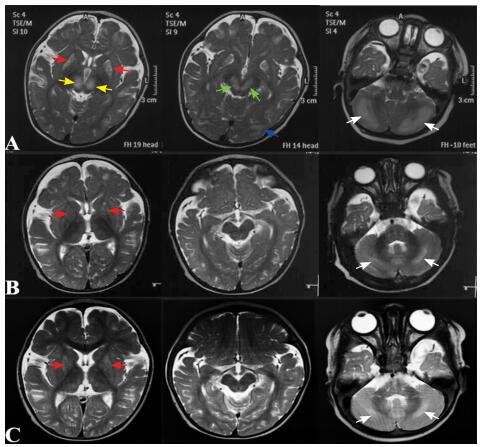

患儿,男,6个月26 d,因阵发性哭闹伴运动倒退2月余于2017年12月11日入院。4.5月龄时无诱因出现阵发性哭闹,初可安抚,按“肠痉挛”处理后好转2~3 d,继之哭闹增多,精神差,肢体运动减少。6月龄时,患儿整天哭闹,伴姿势异常,表现为头后仰、双手后伸,似角弓反张样,不易安抚,并出现眼神呆滞,不喜笑,竖头不稳,不能翻身,四肢活动少。当地完善头颅MRI(淄博市中西医结合医院,2017年11月8日)示双侧豆状核、丘脑、中脑、小脑半球、皮层下白质对称性长T1长T2信号,T2 Flair高信号(图 1A)。2017年11月13日于我科门诊就诊,考虑Leigh综合征及生物素-硫胺素反应性基底节病(biotin-thiamine responsive basal ganglia disease, BTBGD),嘱口服硫胺素10 mg/(kg·d)、生物素1 mg/(kg·d)及“鸡尾酒疗法”(辅酶Q10、左卡尼汀、多种维生素等),建议完善基因检测。服药后患儿精神好转,为进一步诊治收入我科。

|

图 1 生物素-硫胺素反应性基底节病患儿头颅MRI A:6月龄时双侧豆状核(红色箭头)、丘脑内侧(黄色箭头)、中脑(绿色箭头)、小脑半球(白色箭头)、皮层下白质(蓝色箭头)对称性的T2WI高信号;B:7月龄时原病灶较前明显减少,双侧壳核(红色箭头)、小脑半球(白色箭头)T2WI信号略增高;C:1岁时双侧壳核(红色箭头)、小脑半球(白色箭头)病变较7月龄时未见明显变化。 |

患儿系第1胎第1产,足月顺产,出生时无窒息史,出生体重3.85 kg,新生儿期无病理性黄疸。早期发育基本正常:3月龄抬头,4月龄翻身。既往体健,已接种卡介苗、乙肝疫苗、百日咳疫苗、脊髓灰质炎疫苗。父母体健,非近亲婚配,家族中无遗传疾病史。

入院查体:体重10.2 kg(+1.4 SD),身高76 cm(+2.5 SD),生命体征平稳,易激惹,皮肤毛发无异常,心肺腹无异常。头围44 cm,颅神经无异常,四肢肌力V级,肌张力阵发性增高,腱反射对称引出,踝阵挛阴性,病理征(-),脑膜刺激征(-)。

辅助检查:血乳酸、血氨、肝肾功能、心肌酶正常。脑脊液常规和生化正常。血遗传代谢病氨基酸和酰基肉碱谱分析及尿有机酸分析未见异常。腹部彩超示肝、脾轻度肿大,肠胀气。视频脑电图示双侧枕、颞区不对称,左侧θ活动、尖形慢波发放。Gesell发育量表示适应性、大运动、精细运动、个人社交评价为轻度落后,语言为边缘状态。

2 诊断思维6个月26 d男性患儿,以阵发性哭闹伴运动倒退就诊,起病前无明显诱发因素,表现为易激惹、精神反应差、运动倒退及角弓反张样锥体外系受累等亚急性脑病症状。发病初期头颅MRI示双侧豆状核、中脑、小脑对称性异常信号灶。结合患儿的临床表现及影像学特点初步怀疑Leigh综合征及BTBGD,即予生物素、硫胺素及“鸡尾酒疗法”治疗。药物治疗20多天后,患儿精神状态好转。Leigh综合征除了典型的影像学改变外,常伴有血、脑脊液乳酸及丙酮酸水平的升高,而本例患儿血乳酸、血遗传代谢病氨基酸和酰基肉碱谱分析、尿有机酸分析、脑脊液常规和生化等均未发现异常。故考虑患儿为BTBGD可能性大,但Leigh综合征发作间期血液及脑脊液生化检查可正常,故不能完全排除Leigh综合征。因此建议进一步行全外显子组测序协助诊断,若全外显子组测序阴性,可完善线粒体核基因检测排除线粒体脑病。由于SLC19A3基因调控序列突变也可致病,故仍无法明确致病突变时可考虑全基因组测序寻找病因。

BTBGD对生物素、硫胺素治疗反应好,及时治疗后颅内病变可减轻甚至消失,而Leigh综合征对生物素、硫胺素治疗无反应。需经生物素、硫胺素治疗后定期复查头颅MRI观察颅内病变情况也有助诊断。

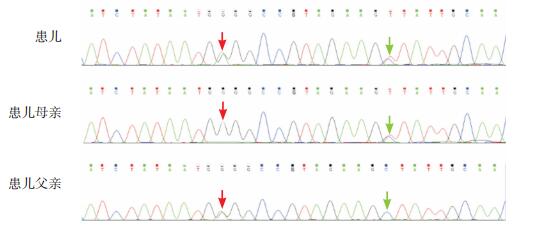

3 进一步检查签署知情同意后,抽取患儿及其家长外周静脉血各2 mL,提取基因组DNA,采用高通量测序仪(Illumina Nextseq500)进行全外显子组测序,并进一步行Sanger测序验证。结果显示患儿SLC19A3基因存在复合杂合变异,分别为c.950G > A(p.G317E)和c.962C > T(p.A321V),前者遗传自父亲,后者遗传自母亲(图 2)。外显子组整合(Exome Aggregation Consortium, ExAC)数据库、千人基因组及dbSNP数据库均未见报道。应用SIFT、PolyPhen-2、Mutation Taster对这两个位点变异进行致病性预测,均为有害突变。

|

图 2 患儿及其父母SLC19A3基因Sanger测序图 患儿SLC19A3基因存在c.950G>A(红色箭头)和c.962C>T(绿色箭头)复合杂合突变,其父母分别为c.950G>A和c.962C>T变异的携带者。突变位点如箭头所示。 |

入院5 d后(硫胺素、生物素治疗1月后),复查头颅MRI(7月龄)示病变显著改善,双侧壳核、小脑半球T2WI信号略增高(图 1B),双侧额部少量硬膜下积液。

4 诊断及确诊依据诊断:生物素-硫胺素反应性基底节病(BTBGD)。依据:(1)亚急性起病,起病初期表现为易激惹、精神反应差、运动倒退及角弓反张样锥体外系受累症状;(2)起病初期头颅MRI(6月龄)有特异性表现:双侧豆状核、中脑、小脑半球、皮层下白质对称性异常信号灶,尤其是双侧丘脑内侧对称性病变;(3)对硫胺素、生物素治疗反应好;(4)SLC19A3基因存在2个复合杂合突变。

5 临床经过入院后继续予口服大剂量硫胺素30 mg/(kg·d)、生物素1 mg/(kg·d)及“鸡尾酒疗法”治疗,复查头颅MRI提示病变明显改善(图 1B)。入院9 d后,患儿精神明显好转,哭闹渐减少,眼神较前灵活,笑容、四肢活动增多,竖头稳,翻身可,异常姿势消失,予出院。

2018年6月(1岁12 d)复查头颅MRI未见新病变,双侧壳核、小脑半球病变较7月龄时无明显变化(图 1C)。头围46 cm,无异常姿势,可独坐,尚不稳,能独站,尚不能独走,有“baba”的发音。嘱其继续口服硫胺素和生物素治疗,并进行康复训练。2018年10月(1岁5月)行电话随访,患儿行康复训练后进步明显:精神反应可,独坐稳,会匍匐爬行,扶着栏杆能快速行走,有“baba”、“mama”的发音,但主动发音少。嘱其继续目前治疗并定期复查头颅MRI观察颅内病变情况。

6 讨论BTBGD也称为硫胺素代谢障碍综合征2(thiamine metabolism dysfunction syndrome-2, THMD2),是一种少见的常染色体隐性遗传的神经代谢障碍性疾病,由Ozand等人于1998年首次报道[1]。BTBGD发病率不详,Ferreira等人[2]曾根据美国人群全基因组测序数据推算BTBGD的发病率为1/215 000,按此发病率估算我国约有6 500名患者。迄今为止,国内仅1例BTBGD女婴的报道[3],生后35 d起病,以易激惹、阵发性哭闹为首发症状。至2018年12月,国外共报道151例BTBGD患者[1-2, 4-41](男性79例,女性72例),发病年龄为18日龄~15岁,平均发病年龄为7岁。BTBGD可发生在各个种族,以沙特阿拉伯人居多,占已报道病例的54%(82/152)。既往文献指出,BTBGD患者父母近亲婚配的发生率高达50%[7]。

2005年,Zeng等[42]首次揭示SLC19A3为该病的致病基因。SLC19A3定位于2q36.3,编码硫胺素转运体2(thiamine transporter 2, THTR2)。在中东患者中,SLC19A3基因c.1264A > G(p.T422A)为最常见的致病突变。在已报道的病例中,SLC19A3的错义突变、无义突变、缺失、重复均可导致BTBGD的发生,以错义突变最为多见。本文报道的SLC19A3基因复合杂合突变是既往文献未报道的突变位点,拓展了SLC19A3基因突变谱。此外,SLC19A3调控区突变也可导致此病的发生[16, 37],故在临床上高度怀疑BTBGD而全外显子组测序或包含SLC19A3基因的靶向测序未发现可疑致病突变时,应考虑SLC19A3全基因组测序进行确诊。

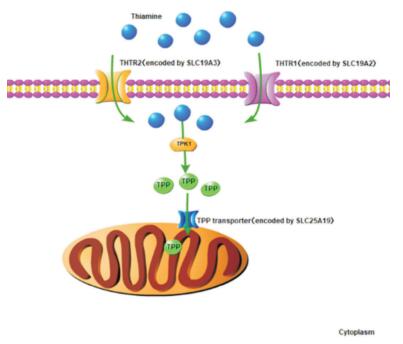

硫胺素是生物体内多种生化反应的重要辅助因子,主要参与能量代谢及核酸、脂质、抗氧化物和神经递质的合成。硫胺素由THTR1(由SLC19A2基因编码)或THTR2转运进入胞质[43],并通过硫胺素焦磷酸激酶1(thiamine pyrophosphokinase 1, TPK1)转化为有活性的硫氨素焦磷酸(thiamine pyrophosphate, TPP)。TPP是细胞质中转酮醇酶的辅助因子,参与磷酸戊糖途径。此外,TPP由线粒体硫胺素焦磷酸载体(由SLC25A19基因编码)转运至线粒体,在线粒体中TPP作为以下3种酶复合物的辅助因子,在能量代谢等生物反应中发挥重要作用[44]:(1)丙酮酸脱氢酶,参与三羧酸循环;(2)α-酮戊二酸脱氢酶,参与三羧酸循环;(3)支链α-酮酸脱氢酶,参与3种支链氨基酸(亮氨酸、异亮氨酸和缬氨酸)的分解代谢。因此,SLC19A2、SLC19A3和SLC25A19基因突变,可导致相应的硫胺素转运载体功能异常,都会引起体内硫胺素代谢障碍(图 3)。

|

图 3 硫胺素代谢通路 硫胺素主要通过THTR1或THTR2转运至细胞质,经TPK1转化为TPP,TPP通过线粒体TPP转运体进入线粒体。[THTR1]硫胺素转运体1;[THTR2]硫胺素转运体2;[TPK1]硫胺素焦磷酸激酶1;[TPP]硫胺素焦磷酸。 |

根据临床表现及发病年龄的不同,将BTBGD分为3型[45]:(1)儿童起病的BTBGD:为最常见的表型,平均发病年龄为7岁,接近半数的病例发病年龄在3~7岁。常以亚急性脑病起病,表现为精神反应差、易激惹、构音障碍、吞咽困难,可伴有核上性面神经瘫痪及眼外肌麻痹症,如不及时治疗,病情可发展为严重的齿轮样强直、肌张力障碍、癫痫、四肢瘫痪,甚至死亡。急性期头颅MRI表现为基底节(尾状核和壳核)、小脑、皮层、皮层下白质水肿。(2)婴儿早期起病的Leigh样综合征或不典型的婴儿痉挛:①Leigh样综合征:通常在生后3个月内起病,表现为喂养困难、呕吐、急性脑病及严重的乳酸酸中毒。头颅MRI可见Rolandic区周围、双侧壳核及丘脑内侧核信号异常,MRS可见乳酸峰。此型患者大部分对生物素、硫胺素治疗不敏感,早期死亡;②不典型婴儿痉挛:此型患者常于生后1~2个月出现神经系统症状如易激惹、角弓反张,并于2~11个月出现不典型婴儿痉挛表现,脑电图常为多灶性棘波,但无高度失律,此型预后差。(3)成年起病的Wernicke's样脑病:此型仅见2例日本男性报道,发病年龄在10~20岁,表现为癫痫持续状态、复视、眼球震颤、上睑下垂、眼肌麻痹及共济失调,头颅MRI示双侧丘脑内侧及导水管周围灰质异常信号。此型患者对大剂量的硫胺素治疗反应好。

BTBGD是一种可治性神经代谢性疾病,大部分患者对硫胺素、生物素治疗反应好。硫胺素的跨膜转运方式有主动转运和被动扩散两种。当浓度低于2 mmol/L时,硫胺素的跨膜运输依赖于主动转运,即需要载体进行跨膜运输。而硫胺素浓度足够高时,可通过被动扩散方式进行转运[13]。因此,大剂量补充硫胺素可提高其被动扩散的效率,以代偿THTR2的功能缺陷。生物素对本病的治疗作用尚不明确,有文献报道给予适量生物素治疗能够缓解临床症状,其可能的机制:一方面生物素是多种线粒体能量代谢所需酶复合物(包括丙酰辅酶A、丙酮酸羧化酶和3-甲基巴豆酰辅酶A羧化酶)的辅助因子[45],大剂量的生物素可激活这些酶复合物的活性,从而在一定程度上代偿硫胺素缺乏所导致的能量代谢紊乱。另一方面,组蛋白的生物素酰化修饰可以调节SLC19A3基因的表达,已有研究表明SLC19A3基因表达依赖于生物素的水平,大剂量生物素可能会上调SLC19A3基因的表达,通过提高产物的表达来增强其保留的部分功能[7, 44, 46]。总之,大剂量硫胺素是BTBGD治疗的关键,生物素可能对病情的缓解有一定的作用。推荐剂量为硫胺素10~40 mg/(kg·d),生物素1~10 mg/(kg·d)[45],患者需终生用药,但在病情稳定后,硫胺素及生物素的剂量可酌情减低。

7 结语BTBGD是一种可治性遗传性疾病,早期发现、及时给予特异性治疗,患者有望获得较好预后。目前国内发现的两例BTBGD患者发病年龄均较早,以易激惹、阵发性哭闹为首发症状,发病后病情进行性加重,予硫胺素、生物素治疗后病情明显好转。因此,临床工作中若高度怀疑患者为BTBGD时,应及早给予硫胺素、生物素治疗,同时进行相关基因检测以明确诊断。

| [1] |

Ozand PT, Gascon GG, Al Essa M, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease:a novel entity[J]. Brain, 1998, 121(Pt 7): 1267-1279. (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Ferreira CR, Whitehead MT, Leon E. Biotin-thiamine responsive basal ganglia disease:identification of a pyruvate peak on brain spectroscopy, novel mutation in SLC19A3, and calculation of prevalence based on allele frequencies from aggregated nextgeneration sequencing data[J]. Am J Med Genet A, 2017, 173(6): 1502-1513. DOI:10.1002/ajmg.a.38189 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

张培元, 刘晓军, 张玉琴. 小婴儿生物素-硫胺素反应性基底节病一例[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2018, 56(6): 462-464. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2018.06.012 (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Adhisivam B, Mahto D, Mahadevan S. Biotin responsive limb weakness[J]. Indian Pediatr, 2007, 44(3): 228-230. (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Alfadhel M, Almuntashri M, Jadah RH, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease should be renamed biotin-thiamineresponsive basal ganglia disease:a retrospective review of the clinical, radiological and molecular findings of 18 new cases[J]. Orphanet J Rare Dis, 2013, 8: 83. DOI:10.1186/1750-1172-8-83 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Bindu PS, Noone ML, Nalini A, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease:a treatable and reversible neurological disorder of childhood[J]. J Child Neurol, 2009, 24(6): 750-752. DOI:10.1177/0883073808329525 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Algahtani H, Ghamdi S, Shirah B, et al. Biotin-thiamineresponsive basal ganglia disease:catastrophic consequences of delay in diagnosis and treatment[J]. Neurol Res, 2017, 39(2): 117-125. DOI:10.1080/01616412.2016.1263176 (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Aljabri MF, Kamal NM, Arif M, et al. A case report of biotinthiamine-responsive basal ganglia disease in a Saudi child:is extended genetic family study recommended?[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2016, 95(40): e4819. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000004819 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Bin Saeedan M, Dogar MA. Teaching neuroimages:MRI findings of biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease before and after treatment[J]. Neurology, 2016, 86(7): e71-e72. DOI:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002372 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Bubshait DK, Rashid A, Al-Owain MA, et al. Depression in adult patients with biotin responsive basal ganglia disease[J]. Drug Discov Ther, 2016, 10(4): 223-225. DOI:10.5582/ddt.2016.01046 (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Debs R, Depienne C, Rastetter A, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease in ethnic Europeans with novel SLC19A3 mutations[J]. Arch Neurol, 2010, 67(1): 126-130. (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Distelmaier F, Huppke P, Pieperhoff P, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease:a treatable differential diagnosis of Leigh syndrome[J]. JIMD Rep, 2014, 13: 53-57. (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Eichler FS, Swoboda KJ, Hunt AL, et al. Case 38-2017. A 20-year-old woman with seizures and progressive dystonia[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 377(24): 2376-2385. DOI:10.1056/NEJMcpc1706109 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

El-Hajj TI, Karam PE, Mikati MA. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease:case report and review of the literature[J]. Neuropediatrics, 2008, 39(5): 268-271. DOI:10.1055/s-0028-1128152 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Fassone E, Wedatilake Y, DeVile CJ, et al. Treatable Leigh-like encephalopathy presenting in adolescence[J]. BMJ Case Rep, 2013, 2013: 200838. (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Flønes I, Sztromwasser P, Haugarvoll K, et al. Novel SLC19A3 promoter deletion and allelic silencing in viotin-thiamineresponsive basal ganglia encephalopathy[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(2): e0149055. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0149055 (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Kassem H, Wafaie A, Alsuhibani S, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease:neuroimaging features before and after treatment[J]. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2014, 35(10): 1990-1995. DOI:10.3174/ajnr.A3966 (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Schänzer A, Döring B, Ondrouschek M, et al. Stress-induced upregulation of SLC19A3 is impaired in biotin-thiamineresponsive basal ganglia disease[J]. Brain Pathol, 2014, 24(3): 270-279. DOI:10.1111/bpa.12117 (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Serrano M, Rebollo M, Depienne C, et al. Reversible generalized dystonia and encephalopathy from thiamine transporter 2 deficiency[J]. Mov Disord, 2012, 27(10): 1295-1298. DOI:10.1002/mds.25008 (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Tabarki B, Al-Shafi S, Al-Shahwan S, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease revisited:clinical, radiologic, and genetic findings[J]. Neurology, 2013, 80(3): 261-267. (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Alfadhel M, Al-Bluwi A. Psychological assessment of patients with biotin-thiamine-responsive basal ganglia disease[J]. Child Neurol Open, 2017, 4: 2329048X. (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Gerards M, Kamps R, van Oevelen J, et al. Exome sequencing reveals a novel Moroccan founder mutation in SLC19A3 as a new cause of early-childhood fatal Leigh syndrome[J]. Brain, 2013, 136(Pt 3): 882-890. (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Gowda VK, Srinivasan VM, Bhat M, et al. Biotin thiamin responsive basal ganglia disease in siblings[J]. Indian J Pediatr, 2018, 85(2): 155-157. DOI:10.1007/s12098-017-2471-5 (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Haack TB, Klee D, Strom TM, et al. Infantile Leigh-like syndrome caused by SLC19A3 mutations is a treatable disease[J]. Brain, 2014, 137(Pt 9): e296. (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Kevelam SH, Bugiani M, Salomons GS, et al. Exome sequencing reveals mutated SLC19A3 in patients with an earlyinfantile, lethal encephalopathy[J]. Brain, 2013, 136(Pt 5): 1534-1543. (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Kohrogi K, Imagawa E, Muto Y, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease:a case diagnosed by whole exome sequencing[J]. J Hum Genet, 2015, 60(7): 381-385. DOI:10.1038/jhg.2015.35 (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Kono S, Miyajima H, Yoshida K, et al. Mutations in a thiaminetransporter gene and Wernicke's-like encephalopathy[J]. N Engl J Med, 2009, 360(17): 1792-1794. DOI:10.1056/NEJMc0809100 (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Muthusamy K, Ekbote AV, Thomas MM, et al. Biotin thiamine responsive basal ganglia disease-a potentially treatable inborn error of metabolism[J]. Neurol India, 2016, 64(6): 1328-1331. DOI:10.4103/0028-3886.193797 (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Ortigoza-Escobar JD, Serrano M, Molero M, et al. Thiamine transporter-2 deficiency:outcome and treatment monitoring[J]. Orphanet J Rare Dis, 2014, 9: 92. DOI:10.1186/1750-1172-9-92 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Pérez-Dueñas B, Serrano M, Rebollo M, et al. Reversible lactic acidosis in a newborn with thiamine transporter-2 deficiency[J]. Pediatrics, 2013, 131(5): e1670-e1675. DOI:10.1542/peds.2012-2988 (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Pronicka E, Piekutowska-Abramczuk D, Ciara E, et al. New perspective in diagnostics of mitochondrial disorders:two years' experience with whole-exome sequencing at a national paediatric centre[J]. J Transl Med, 2016, 14(1): 174. DOI:10.1186/s12967-016-0930-9 (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Pronicki M, Piekutowska-Abramczuk D, Jurkiewicz E, et al. Neuropathological characteristics of the brain in two patients with SLC19A3 mutations related to the biotin-thiamineresponsive basal ganglia disease[J]. Folia Neuropathol, 2017, 55(2): 146-153. (  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Schwarting J, Lakshmanan R, Davagnanam I. Teaching neuroimages:biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease[J]. Neurology, 2016, 86(17): e184-e185. DOI:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002616 (  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Sremba LJ, Chang RC, Elbalalesy NM, et al. Whole exome sequencing reveals compound heterozygous mutations in SLC19A3 causing biotin-thiamine responsive basal ganglia disease[J]. Mol Genet Metab Rep, 2014, 1: 368-372. DOI:10.1016/j.ymgmr.2014.07.008 (  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Tabarki B, Alfadhel M, AlShahwan S, et al. Treatment of biotinresponsive basal ganglia disease:open comparative study between the combination of biotin plus thiamine versus thiamine alone[J]. Eur J Paediatr Neurol, 2015, 19(5): 547-552. DOI:10.1016/j.ejpn.2015.05.008 (  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Tonduti D, Invernizzi F, Panteghini C, et al. SLC19A3 related disorder:treatment implication and clinical outcome of 2 new patients[J]. Eur J Paediatr Neurol, 2018, 22(2): 332-335. (  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Whitford W, Hawkins I, Glamuzina E, et al. Compound heterozygous SLC19A3 mutations further refine the critical promoter region for biotin-thiamine-responsive basal ganglia disease[J]. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud, 2017, 3(6): pii:a001909. DOI:10.1101/mcs.a001909 (  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Yamada K, Miura K, Hara K, et al. A wide spectrum of clinical and brain MRI findings in patients with SLC19A3 mutations[J]. BMC Med Genet, 2010, 11: 171. DOI:10.1186/1471-2350-11-171 (  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Ygberg S, Naess K, Eriksson M, et al. Biotin and thiamine responsive basal ganglia disease-a vital differential diagnosis in infants with severe encephalopathy[J]. Eur J Paediatr Neurol, 2016, 20(3): 457-461. (  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Kamasak T, Havalı C, İnce H, et al. Are diagnostic magnetic resonance patterns life-saving in children with biotin-thiamineresponsive basal ganglia disease?[J]. Eur J Paediatr Neurol, 2018, 22(6): 1139-1149. DOI:10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.06.009 (  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Mir A, Alhazmi R, Albaradie R. Biotin-thiamine-responsive basal ganglia disease-a treatable metabolic disorder[J]. Pediatr Neurol, 2018, 87: 80-81. DOI:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2018.06.006 (  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Zeng WQ, Al-Yamani E, Acierno JS Jr, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease maps to 2q36.3 and is due to mutations in SLC19A3[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 2005, 77(1): 16-26. DOI:10.1086/431216 (  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Ganapathy V, Smith SB, Prasad PD. SLC19:the folate/thiamine transporter family[J]. Pflugers Arch, 2004, 447(5): 641-646. DOI:10.1007/s00424-003-1068-1 (  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Brown G. Defects of thiamine transport and metabolism[J]. J Inherit Metab Dis, 2014, 37(4): 577-585. DOI:10.1007/s10545-014-9712-9 (  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Alfadhel M, Tabarki B. SLC19A3 gene defects sorting the phenotype and acronyms:review[J]. Neuropediatrics, 2018, 49(2): 83-92. DOI:10.1055/s-0037-1607191 (  0) 0) |

| [46] |

Rodriguez-Melendez R, Zempleni J. Regulation of gene expression by biotin (review)[J]. J Nutr Biochem, 2003, 14(12): 680-690. DOI:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2003.07.001 (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 21

2019, Vol. 21