Wiskott-Aldrich综合征(Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, WAS)又称为湿疹血小板减少伴免疫缺陷综合征,是一种少见的X-连锁隐性遗传性疾病,以血小板减少伴血小板体积减小、湿疹、免疫缺陷、易患自身免疫性疾病和恶性肿瘤为特征。1937年Wiskott首次报道3例男性WAS患儿,表现为反复血性腹泻、血小板减少、湿疹及外耳道感染[1]。1954年Aldrich等[2]报道WAS的一个家系,并证实了该病为X-连锁隐性遗传。1989年de Saint Basile等[3]进一步证实WAS的致病基因定位于X染色体短臂着丝粒Xp11.22-p11.23,编码含WAS蛋白(WAS protein, WASp)[4]。由于WAS基因突变及WASp缺乏程度不同,其临床表现和病情严重程度不同,包括典型WAS、X-连锁血小板减少症(X-linked thrombocytopenia, XLT)、间歇性X-连锁血小板减少症(intermittent X-linked thrombocytopenia, IXLT)和X-连锁粒细胞减少症(X-linked neutropenia, XLN)[5]。WAS发病率较低,约1/100万~10/100万[5],国内相关报道较少,为进一步了解我国WAS患儿的临床特点,本文分析总结了中国医学科学院北京协和医学院血液病医院2013年8月至2018年7月确诊的13例WAS患儿的临床资料。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象以2013年8月至2018年7月我院儿童血液病诊疗中心诊断的13例WAS患儿为研究对象其中3例典型WAS、10例XLT。13例患儿均为男性,发病年龄3(1~48)月,确诊年龄24(1~60)月。有明确家族史者仅1例,其母亲携带与患儿相同的WAS NM-000377 Exon 10 c.1006delA移码突变。

诊断标准为符合(1)~(7)条中的1条及以上,且符合第(8)条[6-7]:(1)男性自幼起病;(2)血便、皮肤瘀点、瘀斑等出血表现;(3)反复皮肤湿疹;(4)反复或严重感染(以消化道、呼吸道及外耳道多见);(5)伴或不伴自身免疫疾病和恶性肿瘤;(6)血小板减少,伴平均血小板体积(mean platelet volume, MPV)减小;(7)伴或不伴家族史;(8)明确的WAS基因突变和/或WASp表达异常。

采用电话随访,研究对象随访至死亡或2018年10月1日,随访时间39(3~62)月。

| 表 1 WAS分型标准 |

|

|

| 表 2 WAS评分标准 |

|

|

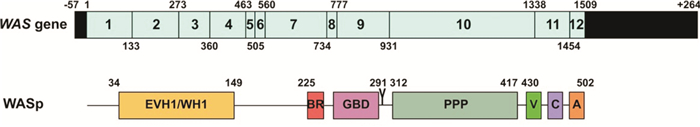

13例患儿均抽取外周血,提取基因组DNA,通过WAS全基因测序行WAS基因突变筛查。WAS基因组DNA长度约为9 kb,包括12个外显子。WASp包含502个氨基酸,5个主要功能区,从N端到C端依次为Ena/VASP同源区1(Ena/VASP homology 1, EVH1)又称为WASP同源区1(WASP homology 1, WH1)、碱性区(basic regionm, BR)、三磷酸鸟苷酶结合区(GTPase binding domain, GBD)、脯氨酸富集区(proline-rich region, PPPP)和C端的VCA区(包括verprolin同源区、cofilin同源区和acidic region酸性氨基酸富集区三部分)。见图 1 [5]。

|

图 1 WAS基因及WASp蛋白结构示意图 |

采用SPSS 19.0统计软件进行数据处理。计量资料用均数±标准差(x±s)或中位数(范围)表示,计数资料用百分率(%)表示。

2 结果 2.1 临床特点13例患儿的WAS评分为2(1~3)分,初诊主诉以皮肤出血点为主,占85%。发病时伴有明显湿疹症状者仅2例,且外用激素可以控制。12例(92%)患儿有反复轻中度感染,主要为呼吸道感染(11/12,85%)。无患儿确诊恶性肿瘤或自身免疫性疾病。见表 3。

| 表 3 13例WAS患儿的临床特点 |

|

|

13例患儿初诊时白细胞8.67(5.0~12.27)×109/L(正常值4~10 ×109/L),血红蛋白108.5(82~127)g/L(正常值120~140 g/L),血小板20.5(13~46)×109/L(正常值100~300×109/L),MPV 8.1(6.7~12.1)fl(正常值9~13 fl)。13例患儿中共2例患儿行骨髓细胞形态学检查,1例未见明显异常,1例巨核细胞增多伴成熟障碍。

共4例患儿行淋巴细胞亚群及免疫球蛋白定量检测,其中IgG升高者1例(25%),IgM下降者2例(50%),IgA下降者1例(25%),4例患儿IgE均升高(100%);淋巴细胞占有核细胞百分比及CD3+T细胞占淋巴细胞百分比均减低者1例(25%);CD3-CD56+NK细胞占淋巴细胞百分比减低者1例(25%),其他各项均正常。

2.2 WAS基因突变特点13例患儿共发现13种14个基因突变,其中错义突变9例(65%),剪接突变2例(14%),无义突变2例(14%),移码突变1例(7%)。14个突变中位于EVH1区者8例(57%),VCA区突变共4例(29%),内含子区突变2例(14%)。14个突变中4例(29%)位于2号外显子,3例(21%)位于1号外显子,1例(7%)位于4号外显子,突变位于10号、11号外显子者各2例(14%),位于10号、11号内含子区者各1例(7%)。13例患儿中仅1例(8%)为复合突变(P460S错义突变联合剪接突变),表现为典型WAS。3例典型WAS患儿的突变均位于VCA区(患儿5、6和7),其中2例为错义突变(67%),1例为移码突变(33%)。见表 4。

| 表 4 13例WAS患儿基因突变检测结果 |

|

|

13例患儿均存活,其中1例接受无关供者异基因脐带血造血干细胞移植,血小板计数恢复正常;余接受激素和/或丙种球蛋白治疗,血小板水平为25(10~50)×109/L。

3 讨论WAS患者大多由于血小板减少引起的出血症状而就诊,容易与其他可导致血小板减少的疾病如免疫性血小板减少性紫癜(immunologic thrombocytopenic purpura, ITP)、伊文氏综合征(Evans syndrome, ES)和再生障碍性贫血(aplastic anemia, AA)混淆[10]。WAS为X-连锁隐性遗传病,多在婴幼儿时期发病,男性为主,血小板减少伴有MPV缩小,血小板抗体检测为阴性,骨髓细胞学检查大多正常,部分患者可伴有感染倾向和反复湿疹。WAS基因突变导致WASp表达减低甚至缺无是WAS的主要发病机制,目前认为WAS基因突变类型与WASp表达及临床表现关系密切,是疾病严重程度评估、治疗方法选择及预后判断的重要依据。国际上已报道300多种基因突变类型,已明确的6个热点突变包括3个剪接位点突变和3个编码区点突变,占所有突变的25%左右,其中突变位于168C > T(T45M)、290C > N/291G > N(R86C/H/L)、IVS6+5G > A者,WASp表达减低,临床症状相对轻微,多表现为XLT;当突变位于665C > T(R211X)、IVS8+1G > N及IVS8+1-+6del GTGA时,WASp多缺失,临床症状较重,表现为典型WAS [11]。本研究T45M热点突变患儿表现为XLT,与报道一致。WAS基因突变最常见的突变位点为EVH1区,多为错义突变,常常仅导致WASp表达水平降低,临床症状相对较轻,多为XLT。本文13例患儿中EVH1区突变者8例,其中7例为错义突变,1例为无义突变,均表现为XLT。VCA区的错义突变、无义突变及剪接位点突变通常导致WASp不表达,临床表现为典型WAS,但少数错义突变如I481N,也可仅表现为IXLT [12]。本文13例患儿中VCA区突变共4例(错义突变3例,移码突变1例),其中3例患儿为典型的WAS,与文献相符[8]。由于病例数有限,本文未检测到GBD区和PPPP区突变。有文献报道[13],132例WAS患儿中仅7例为复合突变,其中6例表现为典型WAS。本文中1例患儿为复合突变,也表现为典型WAS。

WASp表达于各类血细胞和免疫活性细胞,作为细胞骨架及免疫突触形成的重要信号分子,其基因突变可导致多种免疫功能缺陷,目前认为WAS患者的免疫缺陷与T细胞缺陷密切相关,且随年龄的增加而加重[14]。WAS患者T细胞和NK细胞数目可减少,本文共4例患儿行外周血淋巴细胞检测,NK及CD3+T细胞比例下降者均为1例。国外研究中WAS患者外周血IgG、IgA、IgM多减低,IgE多数升高[15]。而国内报道多数WAS患儿IgG、IgA、IgM水平正常或增高,仅少数患儿存在IgG、IgM水平下降,约有75%左右IgE增高[13]。本文4例行免疫球蛋白定量检测的患儿,C3、C4均正常,25%患儿IgG升高,50% IgM减低,25% IgA减低,100% IgE升高。

激素冲击治疗或静脉注射丙种球蛋白对WAS患者血小板减少无明显疗效,但规律的大剂量丙种球蛋白可能改善患者免疫缺陷。脾切除可能改善血小板减少和/或使MPV增加,但发生败血症的风险增加,应当常规使用抗生素预防感染。WAS患者还应密切监测各种感染,包括细菌、病毒、真菌、原虫等,必要时加用抗微生物制剂。严重的湿疹可予以抗感染联合局部外用激素治疗,必要时可短期全身使用糖皮质激素治疗。伴自身免疫性疾病者可适当应用糖皮质激素,但应注意预防感染并警惕恶性肿瘤的发生[16]。异基因造血干细胞移植是目前根治WAS的有效方法,但供者来源、移植物抗宿主病(graft versus host disease, GVHD)、感染等仍是需要重视的问题[17]。有研究报道,与ITP相比,艾曲波帕在WAS患者中疗效较差,部分患者血小板计数可升高,但血小板功能并无改善[18]。此外由于本病是单基因缺陷遗传病,近年来基因治疗也在不断地尝试中,目前在体外实验和动物实验中,已成功地在骨髓细胞、T、B淋巴细胞和血小板中稳定表达WASp [19-21],近年已有成功应用于人体的报道[22],但其长期疗效及安全性仍需进一步研究。本文13例患儿中12例患儿曾接受激素和/或丙种球蛋白治疗,血小板水平改善均不明显,1例患儿行异基因脐带血造血干细胞移植,移植后临床症状完全消失,无严重的GVHD发生。

综上所述,对于发病年龄早、伴有反复感染、皮肤湿疹、自身免疫性疾病的男性血小板减少患儿,无论是否有明确的家族史,均应高度警惕WAS,积极进行基因筛查以明确诊断,有条件时需行WASp定量检测,协助判断疾病严重程度。随着基因筛查技术的应用,WAS患者的确诊年龄提前,误诊率和漏诊率也明显降低,而由于移植技术的发展,WAS患儿的生活质量及预后也在不断提高。近年来基因治疗也在逐渐地完善,有希望成为根治WAS的另一种方法。

| [1] |

Worth AJ, Thrasher AJ. Current and emerging treatment options for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome[J]. Expert Rev Clin Immunol, 2015, 11(9): 1015-1032. DOI:10.1586/1744666X.2015.1062366 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Aldrich RA, Steinberg AG, Campbell DC. Pedigree demonstrating a sex-linked recessive condition characterized by draining ears, eczematoid dermatitis and bloody diarrhea[J]. Pediatrics, 1954, 13(2): 133-139. (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

de Saint Basile G, Arveiler B, Fraser NJ, et al. Close linkage of hypervariable marker DXS255 to disease locus of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome[J]. Lancet, 1989, 2(8675): 1319-1321. (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Derry JM, Ochs HD, Francke U. Isolation of a novel gene mutated in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome[J]. Cell, 1994, 78(4): 635-644. (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Massaad MJ, Ramesh N, Geha RS. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome:a comprehensive review[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2013, 1285: 26-43. DOI:10.1111/nyas.12049 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Zhu Q, Zhang M, Blaese RM, et al. The Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and X-linked congenital thrombocytopenia are caused by mutations of the same gene[J]. Blood, 1995, 86(10): 3797-3804. (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

肖慧勤, 张志勇, 蒋利萍, 等. Wiskott-Aldrich综合征10例临床特点与实验室诊断分析[J]. 免疫学杂志, 2010, 26(1): 43-48. (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Zhu Q, Watanabe C, Liu T, et al. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome/X-linked thrombocytopenia:WASP gene mutations, protein expression, and phenotype[J]. Blood, 1997, 90(7): 2680-2689. (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Ochs HD. The Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome[J]. Isr Med Assoc J, 2002, 4(5): 379-384. (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

赵惠君. Wiskott-Aldrich综合征诊断治疗进展[J]. 中华实用儿科临床杂志, 2016, 31(15): 1129-1132. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-428X.2016.15.003 (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Jin Y, Mazza C, Christie JR, et al. Mutations of the Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome Protein (WASP):hotspots, effect on transcription, and translation and phenotype/genotype correlation[J]. Blood, 2004, 104(13): 4010-4019. DOI:10.1182/blood-2003-05-1592 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Notarangelo LD, Mazza C, Giliani S, et al. Missense mutations of the WASP gene cause intermittent X-linked thrombocytopenia[J]. Blood, 2002, 99(6): 2268-2269. DOI:10.1182/blood.V99.6.2268 (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

李文言, 刘大玮, 张璇, 等. Wiskott-Aldrich综合征132例临床特点及基因型分析[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2015, 53(12): 925-930. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2015.12.012 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Blundell MP, Worth A, Bouma G, et al. The Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome:the actin cytoskeleton and immune cell function[J]. Dis Markers, 2010, 29(3-4): 157-175. DOI:10.1155/2010/781523 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Sullivan KE, Mullen CA, Blaese RM, et al. A multiinstitutional survey of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome[J]. J Pediatr, 1994, 125(6 Pt 1): 876-885. (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Worth AJ, Thrasher AJ. Current and emerging treatment options for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome[J]. Expert Rev Clin Immunol, 2015, 11(9): 1015-1032. DOI:10.1586/1744666X.2015.1062366 (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Moratto D, Giliani S, Bonfim C, et al. Long-term outcome and lineage-specific chimerism in 194 patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome treated by hematopoietic cell transplantation in the period 1980-2009:an international collaborative study[J]. Blood, 2011, 118(6): 1675-1684. DOI:10.1182/blood-2010-11-319376 (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Gerrits AJ, Leven EA, Frelinger AL 3rd, et al. Effects of eltrombopag on platelet count and platelet activation in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome/X-linked thrombocytopenia[J]. Blood, 2015, 126(11): 1367-1378. DOI:10.1182/blood-2014-09-602573 (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Dupré L, Marangoni F, Scaramuzza S, et al. Efficacy of gene therapy for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome using a WAS promoter/cDNA-containing lentiviral vector and nonlethal irradiation[J]. Hum Gene Ther, 2006, 17(3): 303-313. DOI:10.1089/hum.2006.17.303 (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Astrakhan A, Sather BD, Ryu BY, et al. Ubiquitous high-level gene expression in hematopoietic lineages provides effective lentiviral gene therapy of murine Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome[J]. Blood, 2012, 119(19): 4395-4407. (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Boztug K, Schmidt M, Schwarzer A, et al. Stem-cell gene therapy for the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome[J]. N Engl J Med, 2010, 363(20): 1918-1927. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1003548 (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Hacein-Bey Abina S, Gaspar HB, Blondeau J, et al. Outcomes following gene therapy in patients with severe Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome[J]. JAMA, 2015, 313(15): 1550-1563. DOI:10.1001/jama.2015.3253 (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 21

2019, Vol. 21