2. 山西医科大学第二医院血液科, 山西 太原 030001

急性淋巴细胞白血病(acute lymphoblastic leukemia, ALL)是儿童最常见的恶性肿瘤,约占所有儿童肿瘤的20%[1]。目前儿童ALL治愈率为90%左右[2-3],仍有10%~20%的儿童ALL复发[4]。根据预后相关的危险因素进行分层治疗,可降低低危组化疗相关死亡率,对高危组尽早进行强化治疗、适时行造血干细胞移植术,可提高患儿总生存(overall survival, OS)率及无事件生存(event-free survival, EFS)率[5]。目前预后影响因素主要包括患儿初诊时临床特征(年龄、白细胞计数),生物遗传学特征(免疫分型、分子生物学)及对化疗的敏感性[监测微小残留病(minimal residual disease, MRD)] [6]。实际临床工作中发现,除上述因素外,初发ALL患儿个体间血小板计数差异很大,部分患儿血小板计数持续在正常范围。目前少有文献探究儿童ALL初诊时不同血小板水平与预后的关系。Faderl等[7]报道,初发ALL完全缓解患者的血小板恢复越快,无病生存(disease-free survival, DFS)期和OS期越长。凌婧等[8]报道,初诊时ALL患儿血小板计数低者预后较差。本研究拟对我科住院治疗的初诊ALL患儿血小板计数结果进行回顾性分析,探讨不同血小板水平与预后的关系,为进一步提高ALL患儿的疗效提供参考依据。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象选取2008年1月至2015年4月在中国医学科学院血液病医院采用中国儿童白血病协作组(Chinese Children Leukemia Group, CCLG)-ALL 2008(CCLG-ALL 2008)方案治疗的892例初诊ALL患儿为研究对象。所有患儿为初诊患儿,诊断明确前未接受任何治疗,排除其他恶性肿瘤。儿童ALL的诊断、完全缓解、复发标准参照《血液病诊断和疗效标准》[9]。

1.2 资料收集通过查阅病历、末次门诊及住院就诊情况、电话、QQ等方式随访预后,收集患儿的临床信息,包括初诊年龄、性别、血常规、免疫学、分子生物学特征等。随访截止时间为2018年7月,中位随访时间为57(1~123)个月。

1.3 化疗方案根据CCLG-ALL 2008方案[10]中的标准进行危险度分层和治疗。

1.4 分组根据血小板水平进行分组,血小板计数≥100×109/L为血小板正常组,血小板计数<100×109/L为血小板减少组,血小板减少组进一步分为:(50~)×109/L、(20~)×109/L、<20×109/L亚组。血小板计数<50×109/L可能有轻微的出血,血小板计数<20×109/L可有较明显的自发性出血或者内脏出血风险。

1.5 统计学分析采用SPSS 17.0软件进行统计学分析。计量资料以中位数(范围)表示,组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U或Kruskal-Wallis H检验。计数资料以例数和百分率(%)表示,两组间比较采用χ2检验或Fisher确切概率法,多组间比较采用χ2分割法。应用Kaplan-Meier法绘制生存曲线,EFS(从入组开始到发生任何事件的时间,包括复发、治疗相关死亡、第二肿瘤、失访、不明等种种事件)率及OS(从入组开始到因任何原因引起的死亡的时间)率比较采用log-rank法。χ2分割法P=0.05/6=0.0083,余P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 临床资料892例初诊ALL患儿,发病年龄为5(1~15)岁。血小板正常组263例,血小板减少组629例,两组间年龄(Z=-1.601,P=0.109)、性别、免疫分型及部分分子生物学特征(BCR/ABL、TEL/AML1、E2A/PBX1基因阳性)比较差异无统计学意义(分别χ2=3.363、0.724、0.001、0.611、0.534,P=0.067、0.395、0.973、0.434、0.465)。血小板正常组MLL基因重排阳性比例低于血小板减少组(P=0.02)。血小板正常组复发率低于血小板减少组(χ2=5.589,P=0.018)。见表 1~2。初诊血小板减少患儿发生早期出血事件5例,出血致死1例。

| 表 1 各组儿童ALL的临床特征比较 [例(%)或中位数(范围)] |

|

|

| 表 2 各组儿童ALL复发情况 [例(%)] |

|

|

血小板(50~)×109/L、(20~)×109/L、<20×109/L亚组分别243、263、123例。血小板正常组与血小板减少各亚组间年龄(H=3.509,P=0.320)、性别、免疫分型及部分分子生物学特征(BCR/ABL、TEL/AML1、E2A/PBX1基因阳性)比较差异均无统计学意义(分别χ2=0.834、5.727、5.892、2.144、2.933,P=0.841、0.126、0.110、0.543、0.402)。经χ2分割两两比较,血小板正常组与血小板减少各亚组间MLL基因重排阳性比例、复发率差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.0083)。见表 1~2。

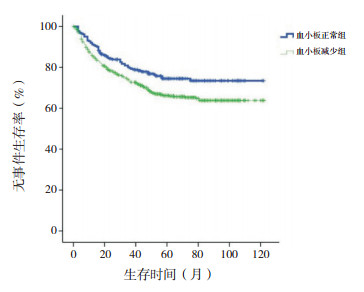

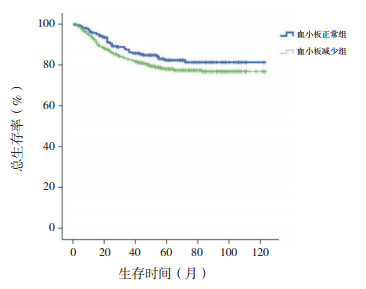

2.2 生存分析血小板正常组10年预期EFS率高于血小板减少组(76%±3% vs 68%±2%,χ2=6.348,P=0.012),血小板正常组与血小板减少组10年预期OS率差异无统计学意义(84%±2% vs 80%±2%,χ2=2.491,P=0.115),见图 1~2。

|

图 1 初诊儿童ALL血小板正常组与血小板减少组无事件生存曲线比较 |

|

图 2 初诊儿童ALL血小板正常组与血小板减少组总生存曲线比较 |

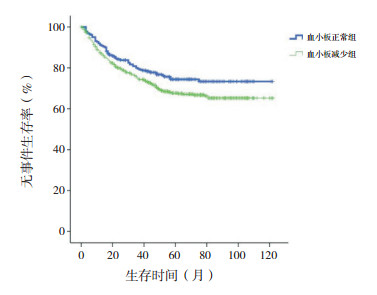

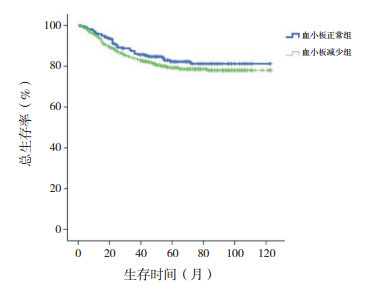

剔除MLL基因重排阳性患儿,血小板正常组10年预期EFS率仍高于血小板减少组(76%±3% vs 69%±2%,χ2=4.140,P=0.042),10年预期OS率差异仍无统计学意义(84%±3% vs 81%±2%,χ2=1.310,P=0.252),见图 3~4。

|

图 3 剔除MLL基因重排阳性初诊儿童ALL血小板正常组与血小板减少组无事件生存曲线比较 |

|

图 4 剔除MLL基因重排阳性初诊儿童ALL血小板正常组与血小板减少组总生存曲线比较 |

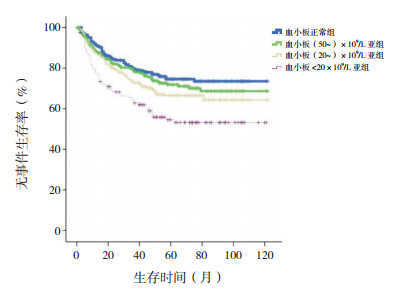

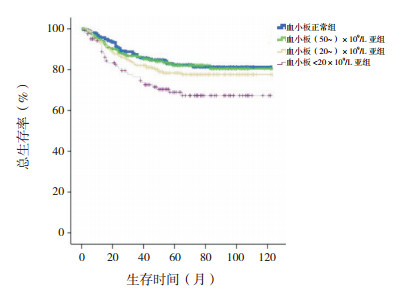

血小板<20×109/L亚组10年预期EFS率低于血小板正常组、(50~)×109/L亚组、(20~)×109/L亚组(分别χ2=17.293、10.620、5.742,P<0.001、P=0.001、0.017),余组间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。血小板<20×109/L亚组10年预期OS率低于血小板正常组、(50~)×109/L亚组、(20~)×109/L亚组(分别χ2=9.393、7.774、3.976,P=0.002、0.005、0.046),余组间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见图 5~6。

|

图 5 初诊儿童ALL血小板正常组、(50~)×109/L亚组、(20~)×109/L亚组、<20×109/L亚组各组无事件生存曲线比较 |

|

图 6 初诊儿童ALL血小板正常组、(50~)×109/L亚组、(20~)×109/L亚组、<20×109/L亚组各组总生存曲线比较 |

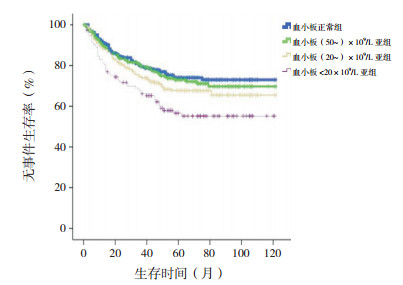

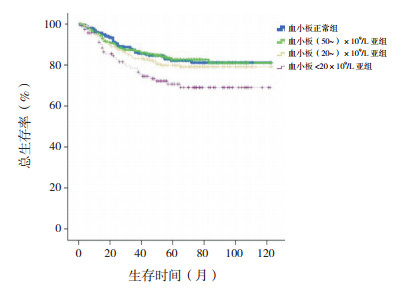

剔除MLL基因重排阳性患儿,血小板<20×109/L亚组10年预期EFS率低于血小板正常组、(50~)×109/L亚组、(20~)×109/L亚组(分别χ2=12.314、8.352、4.077,P<0.001、P=0.004、0.043),余组间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。血小板<20×109/L亚组10年预期OS率低于血小板正常组、(50~)×109/L亚组、(20~)×109/L亚组(分别χ2=6.873、6.236、3.909,P=0.009、0.013、0.048),余组间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见图 7~8。

|

图 7 剔除MLL基因重排阳性初诊儿童ALL血小板正常组、(50~)×109/L亚组、(20~)×109/L亚组、<20×109/L亚组各组无事件生存曲线比较 |

|

图 8 剔除MLL基因重排阳性初诊儿童ALL血小板正常组、(50~)×109/L亚组、(20~)×109/L亚组、<20×109/L亚组各组总生存曲线比较 |

近年来随着医学技术的快速发展,儿童ALL的治愈率逐渐升高[2-3]。通过对ALL患儿的各项预后因素进行评估,按照危险度分层进行诊疗,可降低低危组化疗相关死亡率,针对高危组进行强化治疗,适时行造血干细胞移植术,可改善整体预后[5]。

对于儿童ALL预后影响因素的研究,主要锁定在初诊时临床特征(年龄、白细胞水平),生物遗传学特征(免疫分型、分子生物学)和对治疗的反应(MRD)三方面[6]。目前国际公认的儿童ALL中参与危险度划分及有判断预后意义的分子生物学以TEL/AML1基因、BCR/ABL基因、E2A/PBX1基因及MLL基因重排为主。国内CCLG-ALL 2008同样以TEL/AML1基因、BCR/ABL基因、E2A/PBX1基因及MLL基因重排划分危险度、评估预后。MLL融合蛋白赋予白血病干祖细胞类似造血干细胞的自我更新特性[11],抑制正常造血,成为白血病发生的起因。在婴幼儿、大龄儿童、成人或治疗相关的急性白血病中,不论是ALL抑或是急性髓系白血病,MLL基因重排阳性均提示预后不良[12-13]。本研究结果显示,儿童ALL合并MLL基因重排者临床多表现为血小板计数减少,提示预后不良。

血小板可以存储并分泌细胞因子对于骨髓内膜和血管内皮中造血干细胞的长期生长及造血祖细胞的增殖、分化、短期储存提供一个微环境[14]。特别是血小板分泌的转化生长因子-β,可能促进或抑制造血干祖细胞的增殖、凋亡、分化[15]。血小板在一些恶性肿瘤可能发生改变,且与恶性肿瘤细胞之间存在相互作用:(1)恶性肿瘤患者的血小板可能存在持续活化,如在骨髓增生异常综合征中,血小板-白细胞结合、血小板活化、血小板微粒升高,引起患者动脉或静脉血栓发生风险增加[16];(2)血小板释放可溶性介质(如血管内皮生长因子、血小板衍生生长因子等),通过直接或间接作用影响新血管形成,有利于肿瘤生长[17-18];(3)血小板可增强恶性肿瘤的转移,血小板释放的ATP通过降低内皮屏障功能促进肿瘤转移[19-20]。白血病细胞替代正常骨髓细胞、抑制包括巨核细胞在内的正常血细胞,使血小板计数和功能下降[21]。目前血小板计数对ALL的影响研究甚少,上述机制可为今后研究血小板对ALL的影响提供思路。

本研究对892例初诊儿童ALL的血小板计数进行回顾性分析,发病时血小板计数正常患儿复发率低、预后较好。剔除MLL基因重排患儿,血小板计数正常患儿10年预期EFS率仍明显高于血小板减少组。初诊血小板计数<20×109/L患儿10年预期EFS、OS率明显减低,预后最差。剔除MLL基因重排阳性患儿,血小板<20×109/L患儿10年预期EFS率和10年预期OS率仍显著减低。

儿童ALL初诊血小板水平与患儿预后相关。由于本中心病例数较少,血小板对ALL的影响机制尚不明确,需要多中心研究以扩大临床样本量并完善基础机制研究予以验证。

| [1] |

Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, et al. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2014, 64(2): 83-103. DOI:10.3322/caac.21219 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Kato M, Manabe A. Treatment and biology of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Pediatr Int, 2018, 60(1): 4-12. DOI:10.1111/ped.13457 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Inaba H, Greaves M, Mullighan CG. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia[J]. Lancet, 2013, 381(9881): 1943-1955. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62187-4 (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, et al. Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005:a report from the children's oncology group[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2012, 30(14): 1663-1669. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8018 (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Pieters R, de Groot-Kruseman H, Van der Velden V, et al. Successful therapy reduction and intensification for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia based on minimal residual disease monitoring:study ALL10 from the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2016, 34(22): 2591-2601. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6364 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Stary J, Zimmermann M, Campbell M, et al. Intensive chemotherapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia:results of the randomized intercontinental trial ALL IC-BFM 2002[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2014, 32(3): 174-184. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2013.48.6522 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Faderl S, Thall PF, Kantarjian HM, et al. Time to platelet recovery predicts outcome of patients with de novo acute lymphoblastic leukaemia who have achieved a complete remission[J]. Br J Haematol, 2002, 117(4): 869-874. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03506.x (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

凌婧, 高静, 周雪梅, 等. 初诊儿童急性淋巴细胞白血病血小板计数与预后的关系研究[J]. 中国血液流变学杂志, 2017, 27(3): 247-250. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1009-881X.2017.03.002 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

张之南, 沈悌. 血液病诊断及疗效标准[M]. 第3版. 北京: 科学出版社, 2008: 116-121.

(  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Cui L, Li ZG, Chai YH, et al. Outcome of children with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with CCLG-ALL 2008:the first nation-wide prospective multicenter study in China[J]. Am J Hematol, 2018, 93(7): 913-920. DOI:10.1002/ajh.25124 (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Yokoyama A. Transcriptional activation by MLL fusion proteins in leukemogenesis[J]. Exp Hematol, 2017, 46: 21-30. DOI:10.1016/j.exphem.2016.10.014 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Behm FG, Raimondi SC, Frestedt JL, et al. Rearrangement of the MLL gene confers a poor prognosis in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, regardless of presenting age[J]. Blood, 1996, 87(7): 2870-2877. (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Marschalek R. MLL leukemia and future treatment strategies[J]. Arch Pharm (Weinheim), 2015, 348(4): 221-228. DOI:10.1002/ardp.201400449 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Tabe Y, Konopleva M. Advances in understanding the leukaemia microenvironment[J]. Br J Haematol, 2014, 164(6): 767-778. DOI:10.1111/bjh.12725 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Ruscetti FW, Akel S, Bartelmez SH. Autocrine transforming growth factor-β regulation of hematopoiesis:many outcomes that depend on the context[J]. Oncogene, 2005, 24(37): 5751-5763. DOI:10.1038/sj.onc.1208921 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Villmow T, Kemkes-Matthes B, Matzdorff AC. Markers of platelet activation and platelet-leukocyte interaction in patients with myeloproliferative syndromes[J]. Thromb Res, 2002, 108(2-3): 139-145. DOI:10.1016/S0049-3848(02)00354-7 (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Verheul HM, Pinedo HM. Tumor growth:a putative role for platelets?[J]. Oncologist, 1998, 3(2): Ⅱ. (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Ostman A. PDGF receptors-mediators of autocrine tumor growth and regulators of tumor vasculature and stroma[J]. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2004, 15(4): 275-286. DOI:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.002 (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Gupta GP, Massagué J. Platelets and metastasis revisited:a novel fatty link[J]. J Clin Invest, 2004, 114(12): 1691-1693. DOI:10.1172/JCI200423823 (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Stanger BZ, Kahn ML. Platelets and tumor cells:a new form of border control[J]. Cancer Cell, 2013, 24(1): 9-11. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2013.06.009 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Qian X, Wen-jun L. Platelet changes in acute leukemia[J]. Cell Biochem Biophys, 2013, 67(3): 1473-1479. DOI:10.1007/s12013-013-9648-y (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 21

2019, Vol. 21