2. 湖南省儿童医院, 湖南 长沙 410000

先天性心脏病(congenital heart disease, CHD)简称先心病,是最常见的出生缺陷。据统计,出生缺陷是我国围生期儿死亡的主要原因,其中先心病所占的比例约为1/3[1]。子代患先心病会导致流产、死胎等不良妊娠结局,虽然产前筛检与诊断技术不断普及与发展,但因先心病导致提前终止妊娠、宫内死亡及出生后4周内死亡的患儿仍占48.2%,即便存活,患儿的生长发育及语言能力也将远低于同龄儿童[2-3]。新生儿先心病在亚洲地区的患病率为9.3‰,高于欧洲(8.2‰)及北美地区(6.9‰)[4]。在我国,每年约有13万新生儿患有先心病,患病率约为7‰~8‰[5-6]。由于先心病较高的患病率及不良预后,学者对其危险因素进行了大量的研究[7-8]。近些年越来越多的研究表明,孕妇饮酒与子代先心病的发生存在关联[9-10],然而既往的研究中也有学者指出孕妇饮酒与子代先心病无关[11-12]。考虑到孕妇饮酒与子代先心病患病风险研究结论不一致,未能就孕妇饮酒与子代先心病的关系形成共识,且有关该主题的系统评价较为缺乏,故开展此研究。

1 资料与方法 1.1 检索策略以congenital heart disease、congenital heart defect、congenital heart anomalies、congenital cardiac anomalies、congenital cardiovascular disease、alcohol、drinking、maternal drinking、parental drinking或先天性心脏病、先天性心脏缺陷、先天性心脏畸形、先天性心血管疾病、酒精、饮酒、母亲饮酒、孕妇饮酒为关键词,检索PubMed、Cochrane图书馆、Web of Science数据库、Google学术、中国生物医学文献数据库、万方数据服务平台、中国知网数据库、维普中文科技期刊数据库自建库至2019年11月30日发表的文献。语言种类限定为中文和英文。

1.2 文献纳入与排除标准纳入标准:(1)以上各数据库建库开始至2019年11月30日以中文或英文发表的有关孕妇饮酒与子代先心病结局风险评价的原创性研究;(2)文献设计类型为病例对照研究或队列研究;(3)暴露因素为孕妇孕前或孕期饮酒,非暴露组/对照组的孕妇孕前和孕期不存在饮酒行为;(4)结局指标为子代患有先心病中的一种或多种;(5)报告相对危险度(relative risk, RR)或比值比(odd ratio, OR)及相应95%可信区间(confidence interval, CI)或可获取计算这些指标的数据。

排除标准:(1)重复性文献;(2)资料收集方法不科学,或统计学方法有误或数据缺失的文献。

1.3 文献资料提取及质量评价严格按照文献的纳入与排除标准对文献进行筛选,确定最终纳入文献并提取相关信息。资料的提取由两名研究人员同时独立进行,提取完成后,由第三者对提取的资料进行比对,如出现不一致,则通过集体讨论进行解决。提取内容包括第一作者、发表年份、研究时间、研究地区、研究方法、酒精暴露时期、是否匹配或调整混杂因素、样本量、OR/RR值及95%CI等。参照Newcastle-Ottawa Scale(NOS)量表对所纳入文献进行质量评价[13]。该量表对文献质量的评价采用星级系统半量化原则,满分为9分,当评分≥7分时,视为高质量文献,反之为低质量文献。

1.4 统计学分析计算合并的OR值/RR值及相应的95%CI。采用Cochran Q检验和I2值对各研究进行异质性检验,若P≤0.1或I2 > 50%,表明纳入的研究结果存在异质性,采用随机效应模型分析;反之,采用固定效应模型。采用漏斗图和Egger's检验评估潜在的发表偏倚。通过逐一剔除纳入的单个研究进行敏感性分析以检测结果的稳定性。森林图的制作及亚组分析采用Revman 5.3软件,其他统计分析均采用Stata 15.1软件。

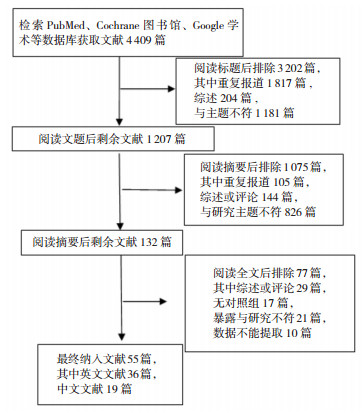

2 结果 2.1 文献纳入结果共检索到文献4 409篇。通过阅读标题、浏览摘要、通读全文及对各数据库中的文献进行相互比对等步骤,剔除重复文献等不符合纳入标准的文献,最终纳入中英文文献共计55篇,其中英文文献[9-12, 14-45] 36篇,中文文献19篇[46-64]。文献纳入流程见图 1。

|

图 1 文献纳入流程图 |

纳入的55篇文献分别来自中国、美国、瑞典、荷兰、芬兰、丹麦、立陶宛、澳大利亚、加拿大等9个国家;总样本量合计498 003人,其中暴露组69 077人,对照组428 926人;6篇为队列研究,49篇为病例对照研究;39篇文献NOS评分≥7分,为高质量文献,16篇为低质量文献。纳入文献的基本情况见表 1。

| 表 1 纳入文献的基本情况 |

|

|

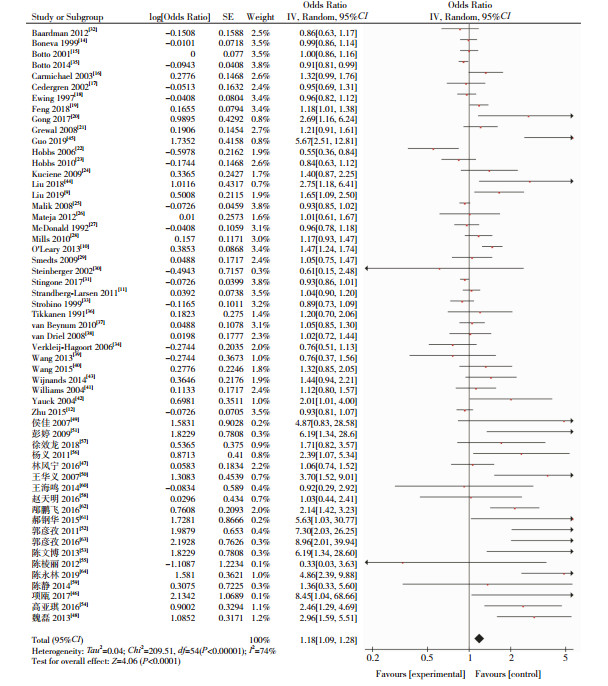

孕妇饮酒与子代先心病患病风险之间的关系在不同的研究间存在异质性(I2=74%,P < 0.001),采用随机效应模型进行分析,显示孕妇饮酒增加子代先心病患病风险(OR=1.18,95%CI:1.09~1.28),见图 2。

|

图 2 孕妇饮酒与子代先心病患病风险的Meta分析森林图 |

依据“研究地域”“研究类型”“酒精暴露时期”“是否调整混杂因素”“文献质量评分”5个变量进行亚组分析,探索相关异质性调节因子。亚组分析结果显示,研究地域、是否调整混杂因素及酒精暴露时期是主要异质性调节因子(P < 0.1)。亚洲人群暴露-反应关系合并效应值高于其他地区的人群(P < 0.001)。若孕期存在酒精暴露,会使子代患先心病的风险较为明显地增加(P < 0.001)。调整了相应的混杂因素后,子代患先心病的风险亦有增加(P < 0.001)。见表 2。

| 表 2 孕妇饮酒与子代先心病患病风险的亚组分析 |

|

|

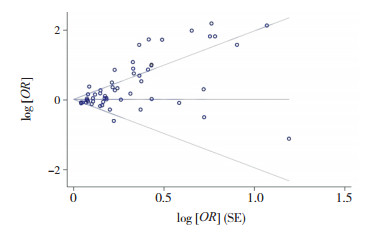

通过逐一剔除单个研究后,发现前后合并效应值并未发现明显变化,其结果相对稳定,合并效应值(包括OR及RR)从1.17(95%CI:1.08~1.27)到1.22(95%CI:1.11~1.33)。本研究漏斗图不完全对称(图 3)。同时采用Egger's检验评价发表偏倚,发现孕妇饮酒与子代先心病患病风险评价的有关文献存在一定的发表偏倚(t=5.91,P < 0.05)。采用剪补法对发表偏倚进行校正后效应值略有降低,但方向并未发生变化,其OR值为1.10(95%CI:1.01~1.21)。

|

图 3 纳入文献发表偏倚的漏斗图 |

目前的研究认为,酒精是对人类健康有害的致畸物[65],因此众多学者将孕妇饮酒视为子代患先心病的潜在危险因素探索两者之间的关联。本研究收集整理了20世纪90年代以来国内外相关文献资料,就孕妇饮酒与子代先心病的患病风险进行了Meta分析。分析结果发现,饮酒孕妇与无酒精暴露的孕妇相比较,其子代患先心病的风险增加18%(95%CI:9%~28%),说明孕妇酒精暴露会增加子代先心病的患病风险,与国内外一些研究结果相符[63, 66-67]。国内学者郭彦孜等[63]的研究指出,先心病的发生与生活环境因素密切相关,而孕早期饮酒是主要的危险因素之一。Tikkanen等[66]的研究结果也表明,孕妇在孕早期接触酒精其后代出现室间隔缺损的风险更大。Zhang等[67]就父母双方饮酒与子代先心病患病风险的Meta分析发现,孕妇若存在酒精暴露,子代先心病发生的风险增加16%(95%CI:5%~27%)。

关于孕前或孕期饮酒使得子代先心病患病风险增加的原因,目前尚未得到证实。有学者认为其可能的原因是酒精暴露使得基因得以改变,从而增加了子代先心病的患病风险[65]。也有研究者认为是酒精暴露对Wnt/β-catenin信号的传导产生了影响,而Wnt/β-catenin信号的传导对正常基因及心脏有关基因的激活均有促进作用[68]。另外一种说法是酒精暴露影响了视黄醇转化为视黄酸以及对N-甲基-D-天冬氨酸受体产生了拮抗作用,导致营养不良和血管破裂进而影响了胎儿的心脏发育[16]。

本研究亚组分析确定了研究地域、是否调整混杂因素及酒精暴露时期是主要异质性调节因子。亚组分析显示,亚洲人群的暴露-反应关系合并效应值高于其他地区的人群,可能的原因是不同国家及地区间检测技术及调查方法存在差异,影响了先心病患病率的流行病学调查结果[1],也可能是由于中西方人群对酒精的耐受存在较大的差异,适合于西方人群的饮酒量不一定适合于亚洲人群[69],致使结果不尽相同。有研究表明,孕早期有饮酒史会较大地增加子代先心病的患病风险[64],而孕期的第2~8周也正是心脏胚胎发育的关键期,此时期内胎儿出现心血管畸形的风险明显升高[60]。Sun等[70]关于孕妇饮酒与子代先心病患病风险评估的Meta分析结果也显示,孕期暴露-反应关系合并效应值高于孕前,本研究结果与之一致。已有研究指出,除母亲孕期饮酒外,子代先心病的发生同时受孕妇年龄、产次、孕期感冒史等多种因素的影响[46]。本研究亚组分析结果表明,调整了相应的混杂因素后,子代患先心病的风险有较为明显的增加。

2015年和2016年发表的有关Meta分析显示,孕妇饮酒与子代先心病患病风险无统计学上的联系[70-71]。与之相比较,本Meta分析纳入的文献更多、更新,结果显示孕妇饮酒可增加子代先心病患病风险。Zhang等[67] 2020年发表的有关Meta分析也显示了孕妇饮酒可增加子代先心病发生的风险。本研究与之比较多纳入了10篇相关文献,研究样本量也更大,提高了统计检验效能。与该Meta分析[67]相同的是,本研究同样存在一定的发表偏倚,但通过校正后,发现结果无明显变化。

本研究分析存在一定局限性。首先,虽然通过敏感性分析结果得出研究结果相对稳定可靠,但漏斗图与Egger's检验结果均表明本Meta分析存在一定的发表偏倚。可能的原因是,虽然所纳入的各项研究均评估了孕妇酒精暴露与子代先心病的风险关系,但我们无法从原始研究中获取暴露酒精的种类,且各地区对酒精暴露的定义也没有统一的标准,使得本研究无法进一步细化。其次,亚组分析能够在一定程度上降低研究之间的异质性,但经亚组分析后异质性仍然存在,故更多的异质性来源有待进一步探讨。第三,本研究纳入文献的设计类型多为病例对照研究,选择偏倚及回忆偏倚难以避免。最后,本研究所纳入的文献仅含中英文,若需得到更为精确的结论,其他语种出版的文献也应包括在内。

综上所述,本Meta分析显示,孕妇酒精暴露会增加子代先心病的患病风险,故适龄女性备孕时应告知酒精暴露的危害,增强孕妇的早期教育,降低子代先心病的发生。

| [1] |

高燕, 黄国英. 先天性心脏病病因及流行病学研究进展[J]. 中国循证儿科杂志, 2008, 3(3): 213-222. (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Yu Z, Xi Y, Ding W, et al. Congenital heart disease in a Chinese hospital:pre- and postnatal detection, incidence, clinical characteristics and outcomes[J]. Pediatr Int, 2011, 53(6): 1059-1065. (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

刘辉, 王伟明, 董巧丽, 等. 河北省儿童先天性心脏病危险因素的研究[J]. 中国妇幼保健, 2009, 24(11): 1496-1497. (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

van der Linde D, Konings EE, Slager MA, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2011, 58(21): 2241-2247. (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

严华林, 华益民. 小分子RNA在先天性心脏病中的研究进展[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2014, 16(10): 1070-1074. (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

何建平, 吴明昌, 任仪荪. 新生儿先天性心脏病145例分析[J]. 中华围产医学杂志, 1999, 2(4): 218-221. (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Begić H, Tahirović HF, Dinarević S, et al. Risk factors for the development of congenital heart defects in children born in the Tuzla Canton[J]. Med Arh, 2002, 56(2): 73-77. (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

李粉, 张兆奉, 郭立燕, 等. CYP450基因多态性及环境危险因素暴露与先天性心脏病关系病例对照研究[J]. 中国公共卫生, 2017, 33(9): 1354-1359. (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Liu C, Lodge J, Flatley C, et al. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in pregnancies with isolated foetal congenital heart abnormalities[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2019, 32(18): 2985-2992. (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

O'Leary CM, Elliottet EJ, Nassar N, et al. Exploring the potential to use data linkage for investigating the relationship between birth defects and prenatal alcohol exposure[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 2013, 97(7): 497-504. (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Strandberg-Larsen K, Skov-Ettrup LS, Grønbaek M, et al. Maternal alcohol drinking pattern during pregnancy and the risk for an offspring with an isolated congenital heart defect and in particular a ventricular septal defect or an atrial septal defect[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 2011, 91(7): 616-622. (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Zhu Y, Romitti PA, Caspers-Conway KM, et al. Maternal periconceptional alcohol consumption and congenital heart defects[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 2015, 103(7): 617-629. (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

曾宪涛, 刘慧, 陈曦, 等. Meta分析系列之四:观察性研究的质量评价工具[J]. 中国循证心血管医学杂志, 2012, 4(4): 297-299. (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Boneva RS, Moore CA, Botto L, et al. Nausea during pregnancy and congenital heart defects:a population-based case-control study[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 1999, 149(8): 717-725. (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Botto LD, Lynberg MC, Erickson JD, et al. Congenital heart defects, maternal febrile illness, and multivitamin use:a population-based study[J]. Epidemiology, 2001, 12(5): 485-490. (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Carmichael SL, Shaw GM, Yang W, et al. Maternal periconceptional alcohol consumption and risk for conotruncal heart defects[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 2003, 67(10): 875-878. (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Cedergren MI, Selbing AJ, Källén BA. Risk factors for cardiovascular malformation-a study based on prospectively collected data[J]. Scand J Work Environ Health, 2002, 28(1): 12-17. (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Ewing CK, Loffredo CA, Beaty TH. Paternal risk factors for isolated membranous ventricular septal defects[J]. Am J Med Genet, 1997, 71(1): 42-46. (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Feng Y, Cai J, Tong X, et al. Non-inheritable risk factors during pregnancy for congenital heart defects in offspring:a matched case-control study[J]. Int J Cardiol, 2018, 264: 45-52. (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Gong W, Liang Q, Zheng D, et al. Congenital heart defects of fetus after maternal exposure to organic and inorganic environmental factors:a cohort study[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(59): 100717-100723. (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Grewal J, Carmichael SL, Ma C, et al. Maternal periconceptional smoking and alcohol consumption and risk for select congenital anomalies[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 2008, 82(7): 519-526. (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Hobbs CA, James SJ, Jernigan S, et al. Congenital heart defects, maternal homocysteine, smoking, and the 677 C>T polymorphism in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene:evaluating gene-environment interactions[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2006, 194(1): 218-224. (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Hobbs CA, Cleves MA, Karim MA, et al. Maternal folate-related gene environment interactions and congenital heart defects[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2010, 116(2): 316-322. (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Kuciene R, Dulskiene V. Maternal socioeconomic and lifestyle factors during pregnancy and the risk of congenital heart defects[J]. Medicina (Kaunas), 2009, 45(11): 904-909. (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Malik S, Cleves MA, Honein MA, et al. Maternal smoking and congenital heart defects[J]. Pediatrics, 2008, 121(4): e810-e816. (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Mateja WA, Nelson DB, Kroelinger CD, et al. The association between maternal alcohol use and smoking in early pregnancy and congenital cardiac defects[J]. J Women Health (Larchmt), 2012, 21(1): 26-34. (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

McDonald AD, Armstrong BG, Sloan M. Cigarette, alcohol, and coffee consumption and congenital defects[J]. Am J Public Health, 1992, 82(1): 91-93. (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Mills JL, Troendle J, Conley MR, et al. Maternal obesity and congenital heart defects:a population-based study[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2010, 91(6): 1543-1549. (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Smedts HP, de Vries JH, Rakhshandehroo M, et al. High maternal vitamin E intake by diet or supplements is associated with congenital heart defects in the offspring[J]. BJOG, 2009, 116(3): 416-423. (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Steinberger EK, Ferencz C, Loffredo CA. Infants with single ventricle:a population-based epidemiological study[J]. Teratology, 2002, 65(3): 106-115. (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Stingone JA, Luben TJ, Carmichael SL, et al. Maternal exposure to nitrogen dioxide, intake of methyl nutrients, and congenital heart defects in offspring[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2017, 186(6): 719-729. (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Baardman ME, Kerstjens-Frederikse WS, Corpeleijn E, et al. Combined adverse effects of maternal smoking and high body mass index on heart development in offspring:evidence for interaction?[J]. Heart, 2012, 98(6): 474-479. (  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Strobino B, Abid S, Gewitz M. Maternal lyme disease and congenital heart disease:a case-control study in an endemic area[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1999, 180(3 Pt 1): 711-716. (  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Verkleij-Hagoort AC, de Vries JH, Ursem NT, et al. Dietary intake of B-vitamins in mothers born a child with a congenital heart defect[J]. Eur J Nutr, 2006, 45(8): 478-486. (  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Botto LD, Panichello JD, Browne ML, et al. Congenital heart defects after maternal fever[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2014, 210(4): 359. (  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Tikkanen J, Heinonen OP. Maternal exposure to chemical and physical factors during pregnancy and cardiovascular malformations in the offspring[J]. Teratology, 1991, 43(6): 591-600. (  0) 0) |

| [37] |

van Beynum IM, Kapusta L, Bakker MK, et al. Protective effect of periconceptional folic acid supplements on the risk of congenital heart defects:a registry-based case-control study in the northern Netherlands[J]. Eur Heart J, 2010, 31(4): 464-471. (  0) 0) |

| [38] |

van Driel LM, de Jonge R, Helbing WA, et al. Maternal global methylation status and risk of congenital heart diseases[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2008, 112(2 Pt 1): 277-283. (  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Wang C, Xie L, Zhou K, et al. Increased risk for congenital heart defects in children carrying the ABCB1 Gene C3435T polymorphism and maternal periconceptional toxicants exposure[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(7): e68807. (  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Wang C, Zhan Y, Wang F, et al. Parental occupational exposures to endocrine disruptors and the risk of simple isolated congenital heart defects[J]. Pediatr Cardiol, 2015, 36(5): 1024-1037. (  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Williams LJ, Correa A, Rasmussen S. Maternal lifestyle factors and risk for ventricular septal defects[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 2004, 70(2): 59-64. (  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Yauck JS, Malloy ME, Blair K, et al. Proximity of residence to trichloroethylene-emitting sites and increased risk of offspring congenital heart defects among older women[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 2004, 70(10): 808-814. (  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Wijnands KP, Zeilmaker GA, Meijer WM, et al. Periconceptional parental conditions and perimembranous ventricular septal defects in the offspring[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 2014, 100(12): 944-950. (  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Liu X, Nie Z, Chen J, et al. Does maternal environmental tobacco smoke interact with social-demographics and environmental factors on congenital heart defects?[J]. Environ Pollut, 2018, 234: 214-222. (  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Guo L, Zhao D, Zhang R, et al. A matched case-control study on the association between colds, depressive symptoms during pregnancy and congenital heart disease in Northwestern China[J]. Sci Rep, 2019, 9(1): 589. (  0) 0) |

| [46] |

项瓯. 浙江省温州地区围生儿先天性心脏病相关因素病例对照研究[J]. 疾病监测, 2017, 32(6): 504-508. (  0) 0) |

| [47] |

林风宁.孕前及孕期环境因素与胎儿先天性心脏病关系的探讨[D].福州: 福建医科大学, 2016.

(  0) 0) |

| [48] |

魏磊, 刘金华, 朱伟, 等. 新疆伊犁州儿童先天性心脏病2:1配对病例对照病因分析[J]. 南京医科大学学报(自然科学版), 2013, 33(1): 78-82. (  0) 0) |

| [49] |

侯佳, 桂永浩, 奚立, 等. 先天性心脏病环境危险因素的病例对照研究[J]. 复旦学报(医学版), 2007, 34(5): 652-655. (  0) 0) |

| [50] |

王华义, 景学安, 李栋. 环境因素对先天性心脏病影响的研究[J]. 泰山医学院学报, 2007, 28(5): 338-340. (  0) 0) |

| [51] |

彭婷, 李笑天, 王丽. 孕母叶酸摄入与MTHFR基因C677T多态性对子代先天性心脏病发病风险研究[J]. 环境与健康杂志, 2009, 26(8): 687-690. (  0) 0) |

| [52] |

郭彦孜, 张国成, 苏海砾, 等.先天性心脏病危险因素的病例对照初步研究[J/CD].中华临床医师杂志(电子版), 2011, 5(15): 4406-4413.

(  0) 0) |

| [53] |

陈文博, 魏晓娟, 陈书影, 等. 中国汉族人群谷胱甘肽硫转移酶M1及T1基因多态性与先天性心脏病发病风险的关系[J]. 岭南心血管病杂志, 2013, 19(4): 450-456. (  0) 0) |

| [54] |

高亚琪.孕早期非遗传因素与先天性心脏病的病例对照研究[D].福州: 福建医科大学, 2016. http://www.cqvip.com/QK/90631X/201421/661706174.html

(  0) 0) |

| [55] |

陈棱丽.围产儿先天性心脏病影响因素的流行病学研究[D].长沙: 中南大学, 2012. http://med.wanfangdata.com.cn/Paper/Detail?id=DegreePaper_Y2199356

(  0) 0) |

| [56] |

杨义.衡阳市围生儿先天性心脏病监测分析及其危险因素研究[D].衡阳: 南华大学, 2011. http://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/thesis/D521449

(  0) 0) |

| [57] |

徐效龙, 祁国荣, 路霖, 等. 我国高原地区先天性心脏病影响因素的病例对照研究[J]. 中国预防医学杂志, 2018, 19(1): 1-4. (  0) 0) |

| [58] |

赵天明.华东两市新生儿先天性心脏病检出情况及影响因素分析[D].北京: 北京协和医学院, 2016. http://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/zgxhzz2016z1012

(  0) 0) |

| [59] |

陈静, 逯素艳, 李炜, 等. 沧州市2003~2012年先天性心脏病非遗传危险因素的病例对照研究[J]. 临床荟萃, 2014, 29(11): 1285-1287. (  0) 0) |

| [60] |

王海鸣, 毛红芳, 荣荷花, 等. 上海市嘉定区先天性心脏病危险因素分析[J]. 上海预防医学, 2014, 26(12): 713-714. (  0) 0) |

| [61] |

郝钢华, 马玉洋, 蒲慧然. 母体不良因素对子代发生复杂型先心病的影响[J]. 中国优生与遗传杂志, 2015, 23(10): 94-96. (  0) 0) |

| [62] |

邴鹏飞. 孕妇尿氟含量等因素与新生儿先天性心脏病的关系[J]. 蚌埠医学院学报, 2016, 41(5): 643-645. (  0) 0) |

| [63] |

郭彦孜, 刘俊, 郑玲芳, 等. 2011-2014年西安咸阳地区先天性心脏病危险因素分析[J]. 临床误诊误治, 2016, 29(1): 80-83. (  0) 0) |

| [64] |

陈永林, 潘金勇, 章伟, 等. 新疆北疆地区儿童先天性心脏病筛查与危险因素分析[J]. 广西医科大学学报, 2019, 36(2): 312-315. (  0) 0) |

| [65] |

Burd L, Deal E, Rios R, et al. Congenital heart defects and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders[J]. Congenit Heart Dis, 2007, 2(4): 250-255. (  0) 0) |

| [66] |

Tikkanen J, Heinonen OP. Risk factors for ventricular septal defect in Finland[J]. Public Health, 1991, 105(2): 99-112. (  0) 0) |

| [67] |

Zhang S, Wang L, Yang T, et al. Parental alcohol consumption and the risk of congenital heart diseases in offspring:an updated systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Eur J Prev Cardiol, 2020, 27(4): 410-421. (  0) 0) |

| [68] |

Serrano M, Han M, Brinez P, et al. Fetal alcohol syndrome:cardiac birth defects in mice and prevention with folate[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2010, 203(1): 75.e7-75.e15. (  0) 0) |

| [69] |

李艺, 彭英. 《慢性酒精中毒性脑病诊治中国专家共识》解读[J]. 中国现代神经疾病杂志, 2019, 19(1): 1-4. (  0) 0) |

| [70] |

Sun J, Chen X, Chen H, et al. Maternal alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy and the risks of congenital heart defects in offspring:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Congenit Heart Dis, 2015, 10(5): E216-E224. (  0) 0) |

| [71] |

Wen Z, Yu D, Zhang W, et al. Association between alcohol consumption during pregnancy and risks of congenital heart defects in offspring:meta-analysis of epidemiological observational studies[J]. Ital J Pediatr, 2016, 42: E216-E224. (  0) 0) |

2020, Vol. 22

2020, Vol. 22