呼吸道合胞病毒(respiratory syncytial virus,RSV)是引起全球婴幼儿下呼吸道感染的最主要病毒病原[1],感染RSV后可致毛细支气管炎及肺炎等,甚至可引起呼吸衰竭。文献报道,RSV感染主要集中在0~2岁的婴幼儿,婴幼儿时期重症RSV感染与学龄期持续喘息、罹患哮喘、肺功能减退有关[2]。然而至今尚无有效的疫苗预防,已造成极大的医疗负担。RSV可分为A和B亚型,A和B亚型又根据基因序列的不同分为不同的亚型[3]。RSV全年均可检出,温带地区主要在冬季流行,而热带地区以雨季为主[4]。在全球不同国家、不同地区RSV流行模式不尽相同,故了解一个地区的RSV流行规律有重要意义。本研究分析了2013~2018年重庆医科大学附属儿童医院呼吸中心住院患儿连续5个流行季RSV流行特征,以期为后续RSV分子流行病学研究提供线索。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象本研究回顾性分析了2 066例2013年6月至2018年5月于重庆医科大学附属儿童医院呼吸中心住院,且已完善鼻咽抽吸物16种常见呼吸道病毒检测患儿的临床资料。纳入标准:(1)符合急性下呼吸道感染诊断标准[5];(2)年龄小于2岁。排除严重心肺疾病、使用免疫抑制剂及患免疫缺陷病、病例资料不全的患儿。

本研究已通过我院伦理委员会审查[审查编号:(2015)年伦审(研)第(77-1)号]。

1.2 样本收集及处理由专科护士于患儿入院后24 h内采集患儿鼻咽抽吸物标本。每管鼻咽抽吸物中加入病毒保护液2 mL,置于-80℃冰箱备用。

1.3 核酸提取及cDNA合成利用核酸提取试剂盒(Qiagen,货号:57704)提取鼻咽抽吸物标本中的病毒核酸,采用SuperScriptTM Ⅲ Reverse Transcriptase System(Invitrogen,货号:18080-044)试剂盒合成cDNA,操作均严格按说明书执行。

1.4 呼吸道常见病毒的检测及分型根据文献[6-7]采用多重PCR分两轮检测鼻咽抽吸物中常见的呼吸道病毒,包括RSV A和B型,流感病毒(IFV)A、B和C型,副流感病毒(PIV)1、2、3和4型,人冠状病毒(HCoV)229E和OC43,人偏肺病毒(HMPV),人鼻病毒(HRV)A、B和C型,人博卡病毒(HBoV),腺病毒(ADV),以及人肠道病毒(HEV)。

1.5 资料收集利用临床信息登记表收集患儿年龄、性别、现病史、家族史、辅助检查、诊断等临床资料。本研究中所有临床疾病(包括肺炎、毛细支气管炎、支气管炎)的诊断标准均依据《诸福棠实用儿科学》第8版[5]。重症下呼吸道感染(包括重症肺炎及重症毛细支气管炎)判断标准[8]为出现以下任何一种情况:(1)一般情况差;(2)有意识障碍;(3)低氧血症表现:紫绀、呼吸增快(婴儿呼吸频率≥70次/mim,1岁以上患儿呼吸频率≥50次/min)、有辅助呼吸(呻吟、鼻扇、三凹征)、间歇性呼吸暂停或氧饱和度 < 92%;(4)发热:超高热或持续高热超过5 d;(5)有脱水征或拒食;(6)胸片或胸部CT提示≥2/3一侧肺浸润、多叶肺浸润、胸腔积液、气胸、肺不张、肺坏死或肺脓肿;(7)有肺外并发症。

1.6 统计学分析采用SPSS 21.0进行统计学分析。正态分布的计量资料应用均数±标准差(x±s)描述,组间比较采用成组t检验;偏态分布计量资料用中位数(四分位数间距)[M(P25,P75)]表示,组间比较采用秩和检验(2组间用Mann-Whitney U检验,3组间用Kruskal-Wallis H检验)。计数资料采用例数和构成比(%)描述,组间比较使用卡方检验或Fisher确切概率检验;多个样本的多重比较采用χ2分割法,调整后的检验水准α'=0.0083。其他组间比较P < 0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 一般临床资料及病毒检出情况本研究共收集2013年6月至2018年5月期间2岁以内急性下呼吸道感染住院患儿鼻咽抽吸物标本2 066份,病毒检出阳性1 595份(77.20%)。其中RSV检出率最高,检出826份(39.98%);其次为HRV,检出521份(25.22%)。其余病毒检出情况如下:PIV 401份(19.41%),HBoV 140份(6.78%),IFV 74份(3.58%),HMPV 54份(2.61%),HCoV 34份(1.65%),HEV 19份(0.92%)。

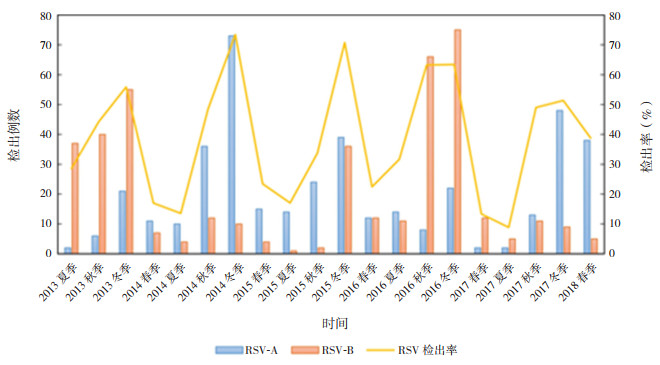

RSV几乎在全年均可检出,其中冬季检出率最高。2013~2014年、2014~2015年、2016~2017年、2017~2018年4个年度RSV流行亚型分别以RSV-B、RSV-A、RSV-B、RSV-A为主导,而2015~2016年为RSV-A和RSV-B共同流行。见图 1。

|

图 1 2013~2018年各季度RSV-A与RSV-B亚型分布 春季指3~5月份;夏季指6~8月份;秋季指9~11月份;冬季指12月份至次年2月份。 |

826例RSV检出阳性样本中,RSV-A阳性410份(49.6%),RSV-B阳性414份(50.1%),RSV-A与RSV-B均阳性2份(0.2%)。RSV检出阳性患儿中,男性562例(68.0%),女性264例(32.0%)。中位年龄为7个月,其中 < 6月龄396例(47.9%),6~11月龄249例(30.1%),12~23月龄181例(21.9%)。中位住院时间为6 d。重症下呼吸道感染患儿206例(24.9%)。

2.3 RSV合并其他病毒检出情况在2 066份样本中,混合感染检出样本464份(22.46%),其中2种病毒合并检出共403份(19.51%)。RSV+HRV组合最常见,检出123份(5.95%)。此外,RSV合并PIV检出55份,合并HBoV 23份,合并IFV 15份,合并ADV 4份,合并HMPV 7份,合并HCoV 4份,合并HEV 9份。3种病毒混合检出59份,4种病毒混合检出2份。

2.4 RSV检出组与其他病毒检出组临床特征分析为比较各病毒病原检出组间的临床特征,本研究排除了所有合并细菌检出的样本,发现单一RSV检出298份,RSV混合其他病毒检出148份,其他病毒检出389份,病毒检出阴性241份。其他病毒检出指除RSV外后,IFV、PIV、HCoV、HMPV、HRV、HBoV、ADV、HEV中任一种或多种病毒检出阳性。与其他病毒检出组和未检出病毒组比较,RSV单一检出组月龄更小,更易发生呼吸困难、呼吸衰竭及重症下呼吸道感染(P < 0.0083);RSV单一检出组喘息比例高于未检出病毒组(P < 0.0083),RSV混合其他病毒组喘息比例高于其他病毒组和未检出病毒组(P < 0.0083)。各组间性别、住院时间、早产史等的比较差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。见表 1。

| 表 1 RSV单一、混合检出与其他病毒检出及未检出病毒组临床特征比较 |

|

|

RSV最易合并HRV,因此本研究比较了单一RSV检出患儿与RSV合并HRV检出患儿的临床特征。结果显示,RSV合并HRV检出患儿更易出现喘息(P=0.030)。两组患儿血白细胞计数差异虽有统计学意义(P=0.022),但均在正常范围内。患儿临床表现、月龄、住院时间、性别构成、早产史比例、湿疹史比例、喘息史比例、疾病严重度、血中性粒细胞比例及血小板计数等差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。见表 2。

| 表 2 单一RSV检出组与RSV合并HRV检出组患儿临床特征比较 |

|

|

在298例RSV单一阳性样本中,有RSV-A阳性151例,RSV-B阳性147例。RSV-A检出阳性患儿中,男性比例更大(P=0.004)。两组患儿月龄、住院时间、临床表现及血常规等实验室数据的比较差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。见表 3。

| 表 3 RSV-A阳性组与RSV-B阳性组患儿临床特征比较 |

|

|

RSV是引起5岁以下儿童下呼吸道感染最主要的病毒病原体[1]。本研究中下呼吸道感染患儿RSV检出率为39.98%,在所检出的病毒中,其检出率最高,且RSV阳性中重症比例较其他病原体阳性患儿明显升高,提示RSV在婴幼儿下呼吸道感染中的重要地位。有系统综述报道RSV在急性呼吸道感染患儿中阳性检出率为12%~63%[9],本组病例与之检出率存在差异可能与纳入对象的年龄、病种、病毒检测方法及地域不同等有关。

既往文献报道,在儿童中,RSV导致的住院率在0~6月龄患儿中最高,主要集中在2~3月龄的婴儿[10]。本研究也有类似发现,RSV阳性患儿中,0~6个月婴儿占比最高(47.94%)。RSV几乎全年均可检出,我国主要流行于10月至次年5月[11]。本研究中RSV在冬季检出率最高。全球范围内RSV-A和RSV-B两种亚型交替模式各不相同:南非2006~2012年以“AABABA”规律流行[12](流行规律中“A”指该年度以RSV-A为主导,“B”指该年度以RSV-B为主导);比利时1996~2005年亚型流行模式由“AAB”循环模式转变为“AB”交替循环[13]。中国各地区流行规律也有差异:北京地区2006~2013年以“AABBAAB”规律流行[14],与浙南[15]、上海[16]等地区在同一时间流行亚型基本类似,但北京地区在2013~2014年、2015~2016年2个流行季出现A、B两种亚型共同主导的情况[14]。本研究中,2013~2014年、2014~2015年、2016~2017年、2017~2018年4个年度RSV流行亚型分别以RSV-B、RSV-A、RSV-B、RSV-A为主导,2015~2016年为RSV-A、RSV-B共同流行。由此可见,在同一流行季不同地区,流行亚型不尽相同,并可出现共同流行的情况,因此研制全球通用的RSV疫苗时应覆盖A、B两种亚型。

RSV是引起婴幼儿喘息最常见的病原体之一。本研究提示,与其他病毒感染患儿相比,RSV感染患儿月龄更小,出现喘息症状可能性更大,且病情较重(呼吸困难、呼吸衰竭、重症下呼吸道感染比例更大)。高钰等[17]对重庆地区2岁以下的急性下呼吸道感染门诊患儿进行临床特征分析,也得出类似结论。陈嘉韡等[18]也报道RSV引起的婴幼儿急性下呼吸道感染病情更重。这可能与RSV感染后对呼吸道上皮细胞存在损伤且持续时间较长、易合并其他病毒感染、继发细菌感染等因素有关。

本研究发现,在RSV合并其他病毒的检出中,HRV最为常见,且RSV合并HRV检出组比单一RSV检出组更易出现喘息。Petrarca等[19]报道,单一RSV检出患儿比RSV合并其他病毒检出患儿更易引起发热,而多种病毒混合检出并未增加患儿的疾病严重度及3年内发生反复喘息的比例。目前对这一问题仍有争议。有学者报道,RSV合并其他病毒感染与单一RSV感染相比,患肺炎比例、住院率及机械通气比例均更高[20],而Papenburg等[21]认为两者病情严重程度无明显不同。

本研究发现RSV 2种亚型引起的下呼吸道感染病情严重度无明显差异。该问题众说纷纭,大部分学者认为RSV-A引起疾病严重度更高[22-23],转入ICU及需要辅助通气的病人比例更高,且RSV-A感染的细胞株和动物模型都表现出更高的病毒滴度和炎症反应[24-25],因此认为RSV-A亚型是重症感染的危险因素。另有学者则认为RSV-B感染所致病情更重[26],还有研究并未发现2种亚型所致病情的差异[27]。出现结果异质性可能原因在于影响病情严重度的不仅是病毒因素,宿主因素也扮演了重要角色,同时各研究的研究方法、样本量大小、检测方法等差异均可能导致结论的不同。

本研究中,RSV-A阳性组的男性比例较RSV-B阳性组更大,而Midulla等[28]、张拓慧等[14]均未发现RSV 2种亚型感染患儿间的性别差异。有研究报道,男性是导致RSV重症感染的危险因素之一,但相关机制尚不明确,推测可能与男性儿童气道树相对狭窄或性激素影响有关[29-30]。

本研究收集了重庆地区连续5个流行季大样本量的临床资料,采用多重PCR对多种呼吸道常见病毒进行检测,发现2013~2018年重庆地区RSV-A与RSV-B既可分别主导流行,也可共同流行;RSV是急性下呼吸道感染住院患儿最主要的病毒病原,相较于其他病毒易致重症下呼吸道感染,合并HRV检出时患儿易发生喘息;RSV-A和RSV-B感染所致临床表现无差异,但RSV-A更易感染男性患儿,为RSV的分子流行病学研究提供了一定线索。本研究未行病毒载量检测及RSV基因型分型,后续研究需进一步完善RSV系统进化分析及病毒载量检测,追踪RSV流行情况,探究RSV分子流行病学规律及与临床特征的关系,为疫苗研发提供思路。

| [1] |

Shi T, McAllister DA, O'Brien KL, et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2015:a systematic review and modelling study[J]. Lancet, 2017, 390(10098): 946-958. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30938-8 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Anderson EJ, Carbonell-Estrany X, Blanken M, et al. Burden of severe respiratory syncytial virus disease among 33-35 weeks' gestational age infants born during multiple respiratory syncytial virus seasons[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2017, 36(2): 160-167. DOI:10.1097/INF.0000000000001377 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Pangesti KNA, Abd El Ghany M, Walsh MG, et al. Molecular epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus[J]. Rev Med Virol, 2018, 28(2): e1968. DOI:10.1002/rmv.1968 (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Griffiths C, Drews SJ, Marchant DJ. Respiratory syncytial virus:infection, detection, and new options for prevention and treatment[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2017, 30(1): 277-319. DOI:10.1128/CMR.00010-16 (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

江载芳, 申昆玲, 沈颖. 诸福棠实用儿科学[M]. 8版.北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2015: 1251-1262.

(  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Coiras MT, Pérez-Breña P, García ML, et al. Simultaneous detection of influenza A, B, and C viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, and adenoviruses in clinical samples by multiplex reverse transcription nested-PCR assay[J]. J Med Virol, 2003, 69(1): 132-144. DOI:10.1002/jmv.10255 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Zheng SY, Wang LL, Ren L, et al. Epidemiological analysis and follow-up of human rhinovirus infection in children with asthma exacerbation[J]. J Med Virol, 2018, 90(2): 219-228. DOI:10.1002/jmv.24850 (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

中华人民共和国国家健康委员会, 国家中医药局. 儿童社区获得性肺炎诊疗规范(2019年版)[J]. 中华临床感染病杂志, 2019, 12(1): 6-13. (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Bont L, Checchia PA, Fauroux B, et al. Defining the epidemiology and burden of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection among infants and children in western countries[J]. Infect Dis Ther, 2016, 5(3): 271-298. DOI:10.1007/s40121-016-0123-0 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Anderson LJ, Dormitzer PR, Nokes DJ, et al. Strategic priorities for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine development[J]. Vaccine, 2013, 31(Suppl 2): B209-B215. (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

谢正德, 肖艳, 刘春艳, 等. 儿童急性下呼吸道感染病毒病原学2007-2010年监测[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2011, 49(10): 745-749. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2011.10.008 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Pretorius MA, van Niekerk S, Tempia S, et al. Replacement and positive evolution of subtype A and B respiratory syncytial virus G-protein genotypes from 1997-2012 in South Africa[J]. J Infect Dis, 2013, 208(Suppl 3): S227-S237. (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Houspie L, Lemey P, Keyaerts E, et al. Circulation of HRSV in Belgium:from multiple genotype circulation to prolonged circulation of predominant genotypes[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(4): e60416. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0060416 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

张拓慧, 邓洁, 钱渊, 等. 毛细支气管炎患儿呼吸道合胞病毒分子生物学及临床特征分析[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2017, 55(8): 586-592. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2017.08.008 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

董琳, 歹丽红, 樊节敏, 等. 浙南地区下呼吸道感染儿童呼吸道合胞病毒基因型流行病学特征及与病情的关系[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2015, 53(7): 537-541. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2015.07.014 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Liu J, Mu YL, Dong W, et al. Genetic variation of human respiratory syncytial virus among children with fever and respiratory symptoms in Shanghai, China, from 2009 to 2012[J]. Infect Genet Evol, 2014, 27: 131-136. DOI:10.1016/j.meegid.2014.07.011 (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

高钰, 王鹂鹂, 张瑶, 等. 呼吸道合胞病毒急性下呼吸道感染门诊患儿临床特征、住院及再发喘息随访研究[J]. 重庆医科大学学报, 2020, 45(6): 776-781. (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

陈嘉韡, 顾文婧, 张新星, 等. 2013年至2015年苏州地区下呼吸道合胞病毒与鼻病毒感染婴儿的临床特征比较[J]. 中华实用儿科临床杂志, 2017, 32(16): 1239-1243. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-428X.2017.16.010 (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Petrarca L, Nenna R, Frassanito A, et al. Acute bronchiolitis:influence of viral co-infection in infants hospitalized over 12 consecutive epidemic seasons[J]. J Med Virol, 2018, 90(4): 631-638. DOI:10.1002/jmv.24994 (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Richard N, Komurian-Pradel F, Javouhey E, et al. The impact of dual viral infection in infants admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit associated with severe bronchiolitis[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2008, 27(3): 213-217. DOI:10.1097/INF.0b013e31815b4935 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Papenburg J, Hamelin MÈ, Ouhoummane N, et al. Comparison of risk factors for human metapneumovirus and respiratory syncytial virus disease severity in young children[J]. J Infect Dis, 2012, 206(2): 178-189. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jis333 (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Yoshihara K, Le MN, Okamoto M, et al. Association of RSV-A ON1 genotype with increased pediatric acute lower respiratory tract infection in Vietnam[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 27856. DOI:10.1038/srep27856 (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Vandini S, Biagi C, Lanari M. Respiratory syncytial virus:the influence of serotype and genotype variability on clinical course of infection[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2017, 18(8): 1717. DOI:10.3390/ijms18081717 (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Wu W, Macdonald A, Hiscox JA, et al. Different NF-κB activation characteristics of human respiratory syncytial virus subgroups A and B[J]. Microb Pathog, 2012, 52(3): 184-191. DOI:10.1016/j.micpath.2011.12.006 (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Fonseca W, Lukacs NW, Ptaschinski C. Factors affecting the immunity to respiratory syncytial virus:from epigenetics to microbiome[J]. Front Immunol, 2018, 9: 226. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00226 (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Hornsleth A, Klug B, Nir M, et al. Severity of respiratory syncytial virus disease related to type and genotype of virus and to cytokine values in nasopharyngeal secretions[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 1998, 17(12): 1114-1121. DOI:10.1097/00006454-199812000-00003 (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Fodha I, Vabret A, Ghedira L, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infections in hospitalized infants:association between viral load, virus subgroup, and disease severity[J]. J Med Virol, 2007, 79(12): 1951-1958. DOI:10.1002/jmv.21026 (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Midulla F, Nenna R, Scagnolari C, et al. How respiratory syncytial virus genotypes influence the clinical course in infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis[J]. J Infect Dis, 2019, 219(4): 526-534. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jiy496 (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Papadopoulos NG, Gourgiotis D, Javadyan A, et al. Does respiratory syncytial virus subtype influences the severity of acute bronchiolitis in hospitalized infants?[J]. Respir Med, 2004, 98(9): 879-882. DOI:10.1016/j.rmed.2004.01.009 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Tse SM, Coull BA, Sordillo JE, et al. Gender-and age-specific risk factors for wheeze from birth through adolescence[J]. Pediatr Pulmonol, 2015, 50(10): 955-962. DOI:10.1002/ppul.23113 (  0) 0) |

2021, Vol. 23

2021, Vol. 23