经外周置入中心静脉导管(peripherally inserted central catheter, PICC)是指经外周静脉置管,导管尖端定位于中心静脉的技术[1]。我国于20世纪90年代开展新生儿PICC,因其具有留置时间长、避免频繁穿刺、减少刺激性药物对血管的损伤等优点,现已广泛应用于新生儿重症监护室(neonatal intensive care unit, NICU)[2-3]。但如操作不当,存在并发症的风险,如导管异位、导管相关血流感染(catheter related blood stream infection, CRBSI)、静脉炎、导管断裂、静脉血栓、导管堵塞等,严重影响患儿的疾病救治,甚至危及生命[4-9]。本指南基于循证证据而制定,以帮助新生儿科医护人员规范PICC操作及管理,预防相关并发症的发生,保证患儿安全。

1 指南的形成 1.1 指南的发起、制定及评审小组本指南由中国医师协会新生儿科医师分会循证专业委员会发起,由新生儿专业医师、新生儿护理团队及循证医学、影像学等领域专家组成指南制定小组,并通过中国医师协会新生儿科医师分会常委组成的外部评审专家组评审。

1.2 指南的注册及计划书的撰写本指南(国际实践指南注册号:IPGRP-2020CN074)目标使用者为新生儿科医生、护理人员等,适用人群为入住NICU的新生儿。本指南以《世界卫生组织指南制定手册(第二版)》为方法学依据,并参考指南研究和评估工具(The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Ⅱ, AGREE Ⅱ)及卫生保健实践指南的报告条目(Reporting Items for Practice Guidelines in Healthcare, RIGHT)而制定[10-13]。

1.3 临床问题的遴选和确定在文献检索的基础上,根据临床实践中遇到的问题,如置管适应证、并发症处理等,提出临床问题。部分问题,如PICC相关风险等内容与患儿监护人充分沟通,考虑其观点,最终根据专家意见形成本指南的关键临床问题。

1.4 证据检索文献的纳入标准:临床指南、专家共识、证据总结、系统评价/Meta分析、随机对照试验及观察性研究。排除标准:不能获得全文、无参考文献的报道、翻译或改编的指南、非中/英文文献、文献质量评价结果为不合格的文献。

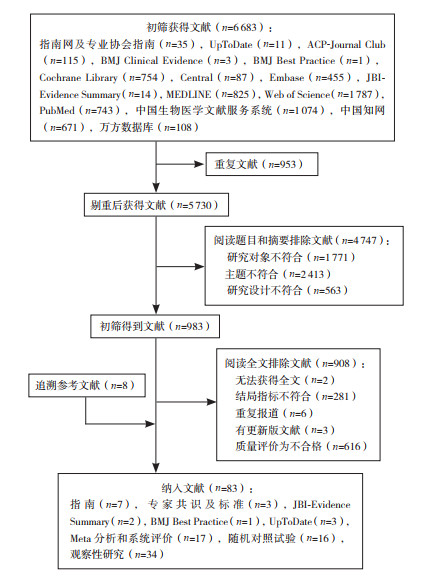

检索平台包括UpToDate、BMJ Clinical Evidence、美国国立指南文库(National Guideline Clearinghouse, NGC)、苏格兰院际间指南网(Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, SIGN)、国际指南协作组(Guidelines International Network, GIN)、英国国家卫生与临床优化研究所(National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NICE)、中国临床指南文库等网页;同时检索JBI循证实践数据库(JBI’s Evidence-based Practice Database)、PubMed、MEDLINE、Embase、Central、Cochrane Library、中国生物医学文献服务系统、中国知网、万方等数据库。检索时限为建库至2020年8月1日。以MeSH主题词加自由词相结合的方式进行检索。检索的MeSH主题词为:“infant, newborn”“catheterizations, peripheral”;自由词为主题词加相关的款目词及文献中的关键词,检索策略在完成预检索后进行完善。文献筛选的流程见图 1。

|

图 1 文献筛选流程图 |

采用证据推荐分级评估、制定与评价方法(Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation, GRADE),以GRADE手册为指导,使用GRADEpro软件及指南制定工具(GRADEpro and the Guideline Development Tool)对纳入的证据进行质量评价和分级[14-15],并综合证据质量和推荐强度形成推荐意见。GRADE将证据质量分为“高、中、低和极低”4个等级(表 1),推荐强度分为“强推荐、弱推荐”2个等级。强推荐指当干预措施明确显示利大于弊或弊大于利时所作推荐;弱推荐指当利弊不确定或无论质量高低的证据均显示利弊相当时所作推荐[10, 16]。

2 推荐意见 2.1 置管适应证推荐意见1:超早产儿(D级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:输注营养液≥5 d(D级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见3:输注高渗性(> 600 mOsm/L)液体(D级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见4:输注pH < 5或pH > 9的液体或药物(D级证据,弱推荐)。

2020年BMJ Best Practice《早产儿管理》提出,超早产儿有潜在的长期肠外营养和用药需求,故推荐将超早产儿纳入置管适应证[17]。

2020年NICE《新生儿肠外营养》提出,经外周静脉输注营养液存在损伤血管的风险,推荐新生儿如需输注营养液≥5 d时应通过中心静脉导管输注[18]。

外周静脉输注高渗性液体时,有发生静脉炎的高风险,且外周静脉只能耐受短时间高渗性液体输注[19-21]。故输注高渗性(> 600 mOsm/L)液体时,推荐行PICC[19]。

研究表明,成年患者经外周静脉输入pH < 5或pH > 9的液体或药物时常有剧烈的烧灼痛[19]。虽目前尚无新生儿相关研究的报道,但考虑到酸碱性较强的液体或药物对血管的损伤,推荐输入pH < 5或pH > 9的液体或药物时行PICC[19, 22]。

2.2 人员资质及培训推荐意见1:推荐组建专业的PICC管理团队(B级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐定期培训医护人员PICC相关知识(B级证据,强推荐)。

PICC应由经过正规培训的工作人员操作,推荐组建专业的PICC管理团队[23-25]。系统评价显示,建立专业的PICC管理团队有利于降低CRBSI发生率,降幅达1.4~10.7/1 000导管日[26-30]。

专业的PICC管理人员,应持续、定期接受培训和评估[25, 31-36]。采取包括培训在内的综合性预防策略能显著降低CRBSI发生率[37-38]。一项队列研究结果显示,培训医护人员血管通路置入及维护的策略可将感染率从9.2/1 000导管日降至3.3/1 000导管日(RR=0.36,95%CI:0.20~0.63,P < 0.05)[35]。

2.3 导管选择推荐意见1:推荐在满足治疗需要的前提下选择小管径的单腔导管(D级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐根据可获得性选用硅胶或聚氨酯材质的导管(D级证据,强推荐)。

2020年《输液导管相关静脉血栓形成中国专家共识》、美国静脉输液护理学会(Infusion Nurses Society, INS)《静脉治疗实践标准(2016年版)》及美国新生儿护士协会(National Association of Neonatal Nurses, NANN)《PICC临床实践指南(第三版) 》提出,选择管径最小、管腔最少的导管以减少静脉炎发生[19, 23-24, 31, 39]。可供选择的PICC管径为1.1~3 Fr(1 Fr=1/3 mm),以1.1~2 Fr较常用[19]。目前国内常用1.9 Fr。管腔主要有单腔和双腔两种,双腔导管多用于接受全肠外营养、多种不相容药物或容量复苏的新生儿,但相比单腔导管,使用双腔导管会增加CRBSI(2.43% vs 4.96%,P=0.015)、血栓形成(0.00% vs 1.22%,P=0.005)、非计划拔管(OR=2.1, 95%CI:1.10~4.10,P < 0.05)的风险[19, 40-41]。故推荐在满足治疗需要的前提下选择小管径的单腔导管以降低并发症的发生率。

新生儿PICC导管有硅胶和聚氨酯两种材质[19, 42]。一项队列研究结果表明,采用硅胶和聚氨酯导管行PICC,堵管、感染、输液渗漏、静脉炎等并发症的总发生率无明显差异[43]。硅胶导管在减少静脉血栓方面具有优势,比聚氨酯导管更耐化学腐蚀;而聚氨酯导管更坚韧,导管破裂的风险较低,但有增加血栓的风险[24, 44]。临床应根据实际情况及可获得性选择导管。

2.4 置管部位及静脉选择推荐意见1:推荐优先选择经下肢静脉置管(B级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐经下肢静脉置管时首选大隐静脉(D级证据,强推荐)。

有研究显示,经上肢静脉置管可降低血栓的发生率(OR=0.23,95%CI:0.07~0.77,P < 0.05)[45]。3项包含10 256例新生儿的Meta分析结果显示,经下肢静脉置管可降低PICC的总并发症发生率,尤其是PICC异位的发生率[45-47]。相比上肢静脉,下肢静脉的一次性置管成功率更高[46-48]。故推荐优先选择经下肢静脉置管。

研究表明,相比经股静脉置管,经大隐静脉行PICC的一次性置管成功率更高,堵管和感染发生率更低,可作为新生儿置管首选[49]。除大隐静脉外,NANN《PICC临床实践指南(第三版)》提出,可供新生儿PICC选择的静脉还有小隐静脉、腘静脉、贵要静脉、肘正中静脉、头静脉、腋静脉、颞浅静脉、耳后静脉及颈外静脉[19]。目前尚未见选择以上不同静脉置管效果排序的报道。故临床应根据实际情况充分权衡不同静脉置管的利弊进行临床决策。

2.5 置管前消毒推荐意见1:推荐使用碘伏消毒皮肤(D级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐使用碘伏消毒后,用无菌0.9%氯化钠溶液清洗碘伏残留物(D级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见3:不推荐使用葡萄糖酸氯己定(chlorhexidine gluconate-impregnated, CGI)或酒精消毒皮肤(D级证据,弱推荐)。

NANN《PICC临床实践指南(第三版)》、美国妇产新生儿护士学会(Association of Women's Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses, AWHONN)/NANN《新生儿皮肤保护临床实践指南》均提出,碘伏可用于新生儿皮肤消毒[19, 50]。

美国疾病预防与控制中心(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC)《预防导管相关血流感染指南》、AWHONN/NANN《新生儿皮肤保护临床实践指南》及近年来的研究均提出,新生儿甲状腺功能异常与含碘消毒剂的暴露有关[25, 50-51]。系统评价显示,胎龄 < 32周的早产儿暴露于碘伏消毒液中可造成甲状腺功能异常[52]。一项RCT结果表明,胎龄 < 32周的早产儿使用碘伏消毒后促甲状腺激素水平增高(P < 0.05)[51]。考虑到碘伏残留物对新生儿甲状腺功能的潜在危害,故推荐使用碘伏消毒且待干后,使用无菌0.9%氯化钠溶液清洗碘伏残留物以减少碘吸收[19, 50]。

尽管有证据表明CGI在成人和儿童中预防CRBSI具有优越性,但目前CGI在新生儿中应用的安全性尚无定论[53-54]。一项前瞻性研究表明,超低出生体重儿(extremely low birth weight infant, ELBWI)生后2 d内使用CGI后,11%发生了红斑和灼伤等皮肤刺激反应[55]。同时CGI在极低出生体重儿(very low birth weight infant, VLBWI)的应用中也有类似不良反应发生[56-58]。故不推荐CGI用于皮肤消毒。另有报道认为,含酒精成分的消毒剂可能导致新生儿皮肤灼伤[59-62]。故不推荐使用酒精用于皮肤消毒。

2.6 辅助置管推荐意见1:推荐采用超声引导辅助置管(A级证据,强推荐)。

超声引导下行PICC可提高首次穿刺成功率、缩短置管时间、减少并发症的发生率[31, 63-66]。欧洲《ESPGHAN/ESPEN/ESPR/CSPEN儿科肠外营养指南:静脉通路》等提出,在超声引导下进行中心静脉置管,可减少并发症的发生[36, 67]。2项RCT结果表明,超声引导下行PICC可减少置管操作时间、降低异位发生率和CRBSI发生率[65, 68]。故推荐采用超声引导辅助置管。

2.7 疼痛管理推荐意见1:推荐使用局部麻醉霜剂(D级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐联合使用鸟巢姿势、抚触、音乐、非营养性吸吮、蔗糖水/母乳安抚等非药物措施(C级证据,强推荐)。

PICC导致的疼痛属于中-重度疼痛范畴,可通过操作前局部使用麻醉药物,并辅以非药物性措施缓解置管疼痛[69]。(1)药物镇痛:NANN《PICC临床实践指南(第三版)》及中国《新生儿疼痛评估与镇痛管理专家共识(2020版)》等提出,置管前60 min使用局部麻醉低熔混合物(eutectic mixture local anesthetics, EMLA),紧急情况下可直接行0.5%~1%利多卡因(2~4 mg/kg)皮下浸润镇痛[19, 69-70]。(2)非药物缓解疼痛:推荐在置管时联合采用多种非药物措施缓解疼痛,包括鸟巢姿势、抚触、音乐、非营养性吸吮、蔗糖水/母乳吸吮安抚等方法[19, 69-73]。系统评价显示,使用以上感觉刺激的综合方法比单用口服蔗糖水更能有效缓解操作性疼痛[74]。

2.8 尖端定位推荐意见1:推荐胸部X片定位PICC尖端(C级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐超声技术定位PICC尖端(C级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见3:推荐腔内心电图技术定位PICC尖端(C级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见4:推荐定位PICC尖端时,患儿体位须保持一致(D级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见5:推荐经下肢静脉置管时,PICC尖端须在下腔静脉内(D级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见6:推荐经头部或上肢静脉置管时,PICC尖端须在上腔静脉内(D级证据,强推荐)。

拍摄胸部X片确认PICC尖端位置是目前使用最多的定位方法,PICC尖端显示率高达100%,但存在X线暴露的危害[75-76]。近年来超声技术和腔内心电图技术(endocavitary electrocardiography, EC-ECG)在PICC尖端定位中应用越来越广泛。超声技术便于动态观察PICC尖端,同时避免了X线暴露。研究显示,使用超声定位的灵敏度为97%~100%,特异度为89.5%~100%[75-79]。另有研究发现,置管过程中采用EC-ECG可观察腔内心电图特异性P波波幅与R波的比例来确定导管尖端位置,定位准确率为89.6%~94.9%[80-83]。但存在波形易受外界因素干扰的缺点。故定位PICC尖端时,临床应根据可及性选择定位方法。

INS《静脉治疗实践标准(2016年版)》[31]及NANN《PICC临床实践指南(第三版)》[19]提出,体位改变,如手臂运动和身体位置的变化均会影响导管尖端的位置和深度。故推荐定位PICC尖端时,患儿每次体位须保持一致。

研究表明,下肢静脉置管时导管尖端须在下腔静脉内,即T9~T11水平之间,可降低PICC相关并发症的发生率[19, 31, 84-85]。

NANN《PICC临床实践指南(第三版)》提出,经头部或上肢静脉置管时,PICC尖端须位于上腔静脉内[19]。INS《静脉治疗实践标准(2016年版)》提出,上腔静脉置管时尖端应位于上腔静脉的下三分之一处[31]。对于身长在47~57 cm的新生儿,中心静脉导管尖端应置于气管隆突(约T5)以上至少0.5 cm,以确保导管尖端置于心包之外,避免心包填塞的发生[36, 86]。一项关于引起患儿心包填塞原因的研究中,有1.3%与中心静脉置管有关,且均发生在新生儿[87]。PICC尖端异位可引起胸腔积液或心包积液。一项纳入3 454例PICC的研究发现,其中10例发生胸腔积液,5例发生心包积液,发生胸腔积液与PICC导管尖端离心脏较远(T2)有关,而发生心包积液与PICC导管尖端离心脏较近(经上肢T6.2,经下肢T5.5)有关[88-89]。故推荐经头部或上肢静脉置管时尖端应位于T4~T6水平之间。

2.9 冲管与封管推荐意见1:推荐用药前后使用0.9%氯化钠溶液冲管(D级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐使用1 IU/mL肝素封管(D级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见3:不推荐常规使用抗生素溶液封管(D级证据,强推荐)。

INS《静脉治疗实践标准(2016年版)》提出,为预防PICC堵管,应进行有效的冲管、封管,冲管和封管之前,应对连接面进行消毒,并采用脉冲式冲管[31]。冲管的0.9%氯化钠溶液量应为导管容积的2倍,频率应视需求而定,用药前后、两种药物使用之间及导管回血时均须冲管[19, 31]。封管宜选用肝素溶液,容积应不少于血管通路装置与附加装置(如三通管)容量之和的1.2倍,且封管液肝素浓度应为1~10 IU/mL[17, 19]。BMJ Best Practice《早产儿管理》推荐预防早产儿中心静脉通路堵管的肝素液有效浓度为1 IU/mL[17]。考虑到新生儿尤其是早产儿凝血功能尚未成熟,推荐使用1 IU/mL的肝素溶液封管以保证安全。

不推荐常规使用抗生素溶液封管,但对多次发生CRBSI且长期使用PICC的患儿,可考虑预防性使用抗生素溶液封管[31]。系统评价显示,使用抗生素封管可预防CRBSI(RR=0.15,95%CI:0.06~0.40,P < 0.05),但因各研究使用的抗生素不同,难以评估不同抗生素的效果[90]。2020年UpToDate《非血液透析导管相关感染的封管治疗》提出,与肝素无配伍禁忌并能长时间保持活性的常用抗生素包括万古霉素、头孢唑林和头孢他啶等[91]。但目前尚无足够证据支持最佳的抗生素选择方案。

2.10 敷料选择与更换推荐意见1:推荐使用无菌透明敷料或纱布敷料覆盖置管处(A级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐在敷料浸湿、松动、污染的情况下及时更换(D级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见3:不推荐使用含氯己定的敷料(B级证据,强推荐)。

《预防导管相关性血流感染指南》提出,应使用无菌透明敷料或纱布敷料覆盖置管处[25]。系统评价结果显示,透明敷料和纱布敷料对CRBSI发生率的差异无统计学意义(RR=0.71,95%CI:0.20~2.52,P > 0.05)[92]。但透明敷料可更好地观察穿刺点情况。

NANN《PICC临床实践指南(第三版)》及CDC《预防导管相关血流感染指南》推荐儿童透明敷料更换应依据临床实际所需,如在透明敷料浸湿、松动、污染的情况下更换[19, 24-25, 37, 93]。新生儿尤其是VLBWI,更换PICC敷料过频可能引起皮肤损伤。故推荐在敷料浸湿等情况下进行更换,不推荐定时更换。

系统评价显示,与透明敷料相比,CGI敷料可以减少CRBSI发生率(RR=0.51,95%CI:0.33~0.78,P < 0.05),但可引起严重的局限性接触性皮炎[94]。有系统评价和RCT显示,CGI引起新生儿皮肤损伤的发生率高,有15%的VLBWI出现了局限性接触性皮炎[95-96]。故不推荐使用CGI敷料。

2.11 PICC拔管推荐意见1:推荐治疗不需要PICC时拔管(D级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐高度怀疑或已发生CRBSI时拔管(D级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见3:不推荐发生血栓后常规拔管(B级证据,强推荐)。

多中心队列研究结果表明,置管2周后发生CRBSI的风险会明显增加(RR=2.04,95%CI:1.12~3.71,P < 0.05),故应每日评估是否需要保留PICC,当不再需要时及时拔管[97]。

《输液导管相关静脉血栓形成中国专家共识》和INS《静脉治疗实践标准(2016年版)》提出,高度怀疑或已发生CRBSI及其他严重并发症时拔管[31, 39, 98]。

现有证据均不推荐发生血栓后常规拔管[25, 31, 99-100]。拔管后另选静脉置管会有86% 的风险再次出现血栓[101]。一项队列研究结果表明,重复置管会增加血栓的风险(OR=6.00,95%CI:2.25~16.04,P < 0.05)[102]。若发生PICC相关血栓后患儿仍有PICC需求,可在抗凝治疗下继续保留导管[31, 99-100, 103]。故不推荐在发生血栓后常规拔管。

2.12 并发症的预防及处理推荐意见1:推荐持续输注0.5 IU/(kg · h)的肝素以降低堵管发生率(A级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐应用集束化护理以预防CRBSI(A级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见3:不推荐使用肝素预防PICC相关血栓的形成(A级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见4:推荐冲管和封管时使用≥10 mL注射器,遇阻力停止冲管,采用轻柔拔管预防导管断裂(D级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见5:推荐拔管困难时暂缓拔管,经热敷后再尝试拔管(D级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见6:推荐拔管失败后使用扩血管药物外敷静脉、导丝引导拔管,必要时手术取出导管(D级证据,弱推荐)。

3项系统评价和Meta分析显示,持续输注肝素可降低新生儿PICC堵管率[104-106]。2项RCT结果表明,持续输注0.5 IU/(kg · h)的肝素,可有效降低PICC堵管率,且无其他不良反应[107-108]。持续输注肝素的方式各异,大多采用在全肠外营养中加入肝素输注的方式[107, 109-111],也有采用将肝素加入10%葡萄糖或5%葡萄糖溶液中输注的方式[108, 112]。但目前尚无证据支持哪种方式更优。

Meta分析和系统评价结果显示,应用集束化护理可有效预防CRBSI[94, 113-114]。集束化护理内容主要包括:正确消毒皮肤、保持穿刺时最大化无菌屏障、严格执行手卫生、选择合适的导管与置管静脉、每日评估导管是否需要等[113-114]。

系统评价显示,肝素输注组与无肝素输注组间的血栓发生率差异无统计学意义(RR=0.93,95%CI:0.58~1.51,P > 0.05),肝素不能预防PICC相关血栓发生[104, 115]。故不推荐使用肝素预防PICC相关血栓的形成。

PICC导管体内断裂可威胁患儿生命。研究发现,带管时间、导管相关并发症与导管断裂显著相关[116]。NANN《PICC临床实践指南(第三版)》提出,使用小容量注射器产生的较大压强、用力拔管等不恰当的操作均可能造成导管断裂。故应使用≥10 mL容量的注射器进行冲管和封管,如遇阻力应停止冲管,以免造成导管断裂。另外,强行拔管等不当操作也是造成导管断裂的重要原因,故拔管时应轻柔[19]。一旦发生导管断裂,应用止血带压住穿刺点上方静脉阻断静脉血流,以防止断裂碎片随血流移动,止血带的松紧应以不阻断动脉血流为宜。同时应立即拍摄胸部X片确认断裂端的位置,如断裂碎片留在外周静脉,可采取静脉切开术取出,如断裂碎片留在中心静脉,则需通过介入手术或心胸外科手术取出[19]。

拔管困难时应立即停止并评估原因。可尝试用0.9%氯化钠溶液沿静脉走向热敷穿刺点上方静脉20~30 min,若拔管仍困难,应间歇热敷,并于12~24 h后再次尝试拔管1~2次[19]。如仍失败则考虑使用扩血管药物外敷静脉、导丝引导拔管或手术取出[117-118]。

3 小结新生儿PICC在临床中应用广泛,规范PICC的操作及管理对降低并发症的发生极为重要。本指南基于目前国内外能获取的证据,根据GRADE方法进行证据分级,并经同行专家认真讨论后形成,以期为临床工作者提供参考。在应用过程中可能遇到技术及设备条件不足等障碍因素,如超声引导辅助置管及尖端定位、EC-ECG技术等,应根据所在单位实际情况开展。本指南拟3年更新一次,在检索新的证据后咨询专家意见、收集使用人群及目标人群的意见,形成指南更新决策证据表,遵循RIGHT及指南更新报告清单进行更新。本指南共有37条推荐意见,其中A级5条(14%),B级5条(14%),C级4条(11%),D级23条(62%)。高级别证据较少,这可能与新生儿PICC多应用于危重新生儿,RCT设计严格,实施难度大有关,需进一步进行临床研究,但本指南呈现的是现有可获得的最佳证据。本指南推荐意见汇总见表 2。

| 表 2 新生儿PICC操作及管理指南推荐意见 |

|

|

执笔人:陈琼、李颖馨、胡艳玲、唐军、封志纯、母得志

编写专家委员会(按专家所在单位名拼音排序):北京大学第三医院(童笑梅、邢燕)、北京市朝阳区妇幼保健院(刘敬、任晓玲)、北京儿童医院(黑明燕)、成都市妇女儿童中心医院(巨容)、福建省厦门市妇幼保健院(林新祝)、广西壮族自治区妇幼保健院(郭小芳)、广州市妇女儿童医疗中心(周伟)、贵州省妇幼保健院(刘玲)、哈尔滨医科大学第一附属医院(王竹颖)、南京医科大学附属儿童医院(周晓玉)、山东省青岛市妇女儿童医院(刘秀香)、山西省儿童医院(刘克战)、上海市儿童医院(裘刚)、深圳市妇幼保健院(杨传忠)、首都儿科研究所附属儿童医院(李莉)、四川大学华西第二医院(陈琼、胡艳玲、李颖馨、母得志、宁刚、唐军、唐英)、西安交通大学第一附属医院(刘俐)、新疆医科大学第一附属医院(李明霞)、中国人民解放军第三〇二医院(张雪峰)、中国人民解放军总医院第七医学中心附属八一儿童医院(封志纯)、中南大学湘雅医院(岳少杰)。

利益冲突声明:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突;不存在商业利益冲突。

特别志谢: 衷心感谢四川大学华西医院中国循证医学中心李幼平教授在指南设计、证据分析及指南写作中给予的支持和帮助。

| [1] |

苏绍玉, 胡艳玲. 新生儿临床护理精粹[M]. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2017: 388.

(  0) 0) |

| [2] |

杨海娥, 刘惠丽. 新生儿PICC主要并发症的发生及预防对策[J]. 中华现代护理杂志, 2011, 17(22): 2718-2720. (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Jin JF, Chen CF, Zhao RY, et al. Repositioning techniques of malpositioned peripherally inserted central catheters[J]. J Clin Nurs, 2013, 22(13-14): 1791-1804. DOI:10.1111/jocn.12004 (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Singh A, Bajpai M, Panda SS, et al. Complications of peripherally inserted central venous catheters in neonates: lesson learned over 2 years in a tertiary care centre in India[J]. Afr J Paediatr Surg, 2014, 11(3): 242-247. DOI:10.4103/0189-6725.137334 (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Gilbert R, Brown M, Rainford N, et al. Antimicrobial-impregnated central venous catheters for prevention of neonatal bloodstream infection (PREVAIL): an open-label, parallel-group, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 2019, 3(6): 381-390. DOI:10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30114-2 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Jumani K, Advani S, Reich NG, et al. Risk factors for peripherally inserted central venous catheter complications in children[J]. JAMA Pediatr, 2013, 167(5): 429-435. DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.775 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

胡艳玲, 唐孟言, 李小文, 等. 新生儿PICC导管异位影响因素及预防措施的研究进展[J]. 护理学杂志, 2020, 35(22): 105-108. (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Baggio MA, Bazzi FC, Bilibio CA. Peripherally inserted central catheter: description of its use in neonatal and pediatric ICU[J]. Rev Gaucha Enferm, 2010, 31(1): 70-76. DOI:10.1590/S1983-14472010000100010 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Ohki Y, Maruyama K, Harigaya A, et al. Complications of peripherally inserted central venous catheter in Japanese neonatal intensive care units[J]. Pediatr Int, 2013, 55(2): 185-189. DOI:10.1111/ped.12033 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Organization World Health. WHO Handbook for Guideline Development[EB/OL].[2020-07-16]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/145714/9789241548960_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE Ⅱ: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care[J]. CMAJ, 2010, 182(18): E839-E842. DOI:10.1503/cmaj.090449 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

韦当, 王聪尧, 肖晓娟, 等. 指南研究与评价(AGREE Ⅱ)工具实例解读[J]. 中国循证儿科杂志, 2013, 8(4): 316-319. (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Chen YL, Yang KH, Marušic A, et al. A reporting tool for practice guidelines in health care: the RIGHT statement[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2017, 166(2): 128-132. DOI:10.7326/M16-1565 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE Handbook[EB/OL].[2020-07-16]. https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html.

(  0) 0) |

| [15] |

GRADEpro GDT. GRADE your evidence and improve your guideline development in health care[EB/OL].[2020-07-10]. https://gradepro.org.

(  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Balshem H, Helfanda M, Schunemann HJ, 等. GRADE指南: Ⅲ.证据质量分级[J]. 中国循证医学杂志, 2011, 11(4): 451-455. (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

BMJ Best Practice. Premature newborn care[EB/OL].[2020-07-16]. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/671/pdf/671/Premature%20newborn%20care.pdf.

(  0) 0) |

| [18] |

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Neonatal parenteral nutrition[EB/OL].[2020-07-16]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng154/resources/neonatal-parenteral-nutrition-pdf-66141840283333.

(  0) 0) |

| [19] |

National Association of Neonatal Nurses. Peripherally inserted central catheters: guideline for practice, 3rd edition[EB/OL].[2020-07-16]. http://hummingbirdmed.com/wp-content/uploads/NANN15_PICC_Guidelines_FINAL.pdf.

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Gazitua R, Wilson K, Bistrian BR, et al. Factors determining peripheral vein tolerance to amino acid infusions[J]. Arch Surg, 1979, 114(8): 897-900. DOI:10.1001/archsurg.1979.01370320029005 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Kuwahara T, Asanami S, Tamura T, et al. Effects of pH and osmolality on phlebitic potential of infusion solutions for peripheral parenteral nutrition[J]. J Toxicol Sci, 1998, 23(1): 77-85. DOI:10.2131/jts.23.77 (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Boullata JI, Gilbert K, Sacks G, et al. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: parenteral nutrition ordering, order review, compounding, labeling, and dispensing[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2014, 38(3): 334-377. DOI:10.1177/0148607114521833 (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

李全磊. PICC置管前评估的临床实践指南构建[D]. 上海: 复旦大学, 2012.

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Queensland Government. Guideline: peripherally inserted central venous catheters (PICC)[EB/OL].[2020-07-16]. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0032/444497/icare-picc-guideline.pdf.

(  0) 0) |

| [25] |

O'grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2011, 52(9): e162-e193. DOI:10.1093/cid/cir257 (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Legemaat MM, Jongerden IP, van Rens RM, et al. Effect of a vascular access team on central line-associated bloodstream infections in infants admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit: a systematic review[J]. Int J Nurs Stud, 2015, 52(5): 1003-1010. DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.010 (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Cooley K, Grady S. Minimizing catheter-related bloodstream infections: one unit's approach[J]. Adv Neonatal Care, 2009, 9(5): 209-226. DOI:10.1097/01.ANC.0000361183.81612.ec (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Curry S, Honeycutt M, Goins G, et al. Catheter-associated bloodstream infections in the NICU: getting to zero[J]. Neonatal Netw, 2009, 28(3): 151-155. DOI:10.1891/0730-0832.28.3.151 (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Golombek SG, Rohan AJ, Parvez B, et al. "Proactive" management of percutaneously inserted central catheters results in decreased incidence of infection in the ELBW population[J]. J Perinatol, 2002, 22(3): 209-213. DOI:10.1038/sj.jp.7210660 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Holzmann-Pazgal G, Kubanda A, Davis K, et al. Utilizing a line maintenance team to reduce central-line-associated bloodstream infections in a neonatal intensive care unit[J]. J Perinatol, 2012, 32(4): 281-286. DOI:10.1038/jp.2011.91 (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Infusion Nurses Society. Infusion therapy standards of practice[J]. J Infus Nurs, 2016, 39(1S): S1-S156. (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Yoo S, Ha M, Choi D, et al. Effectiveness of surveillance of central catheter-related bloodstream infection in an ICU in Korea[J]. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2001, 22(7): 433-436. DOI:10.1086/501930 (  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Warren DK, Zack JE, Cox MJ, et al. An educational intervention to prevent catheter-associated bloodstream infections in a nonteaching, community medical center[J]. Crit Care Med, 2003, 31(7): 1959-1963. DOI:10.1097/01.CCM.0000069513.15417.1C (  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Warren DK, Zack JE, Mayfield JL, et al. The effect of an education program on the incidence of central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infection in a medical ICU[J]. Chest, 2004, 126(5): 1612-1618. DOI:10.1378/chest.126.5.1612 (  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Eggimann P, Harbarth S, Constantin MN, et al. Impact of a prevention strategy targeted at vascular-access care on incidence of infections acquired in intensive care[J]. Lancet, 2000, 355(9218): 1864-1868. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02291-1 (  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Kolaček S, Puntis JWL, Hojsak I, et al. ESPGHAN/ESPEN/ESPR/CSPEN guidelines on pediatric parenteral nutrition: venous access[J]. Clin Nutr, 2018, 37(6 Pt B): 2379-2391. (  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Jacob JT, Gaynes R. Intravascular catheter-related infection: prevention[EB/OL].[2020-07-16]. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/zh-Hans/intravascular-catheter-related-infection-prevention.

(  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Blot K, Bergs J, Vogelaers D, et al. Prevention of central line-associated bloodstream infections through quality improvement interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2014, 59(1): 96-105. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciu239 (  0) 0) |

| [39] |

傅麒宁, 吴洲鹏, 孙文彦, 等. 《输液导管相关静脉血栓形成中国专家共识》临床实践推荐[J]. 中国普外基础与临床杂志, 2020, 27(4): 412-418. (  0) 0) |

| [40] |

O'brien J, Paquet F, Lindsay R, et al. Insertion of PICCs with minimum number of lumens reduces complications and costs[J]. J Am Coll Radiol, 2013, 10(11): 864-868. DOI:10.1016/j.jacr.2013.06.003 (  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Isemann B, Sorrels R, Akinbi H. Effect of heparin and other factors associated with complications of peripherally inserted central venous catheters in neonates[J]. J Perinatol, 2012, 32(11): 856-860. DOI:10.1038/jp.2011.205 (  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Di Fiore RE. Clinical and engineering considerations for the design of indwelling vascular access devices-materials and product development overview[J]. J Assoc Vasc Access, 2005, 10(1): 24-27. (  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Yu XH, Yue SJ, Wang MJ, et al. Risk factors related to peripherally inserted central venous catheter nonselective removal in neonates[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2018, 2018: 3769376. (  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Chu WH. Evidence Summary. Peripherally inserted central catheter: occlusion[Z]. The Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database, JBI@Ovid, 2017: JBI652.

(  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Chen HX, Zhang XX, Wang H, et al. Complications of upper extremity versus lower extremity placed peripherally inserted central catheters in neonatal intensive care units: a meta-analysis[J]. Intensive Crit Care Nurs, 2020, 56: 102753. DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2019.08.003 (  0) 0) |

| [46] |

陈秀文, 周乐山, 谭彦娟, 等. 新生儿上肢静脉与下肢静脉PICC置管效果比较的Meta分析[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2019, 21(12): 1164-1171. (  0) 0) |

| [47] |

付贞艳, 权明桃, 陈开永, 等. 新生儿不同静脉置入PICC效果的Meta分析[J]. 护士进修杂志, 2020, 35(3): 218-225. (  0) 0) |

| [48] |

Cartwright DW. Central venous lines in neonates: a study of 2186 catheters[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2004, 89(6): F504-F508. DOI:10.1136/adc.2004.049189 (  0) 0) |

| [49] |

陈秀文, 周乐山, 谭彦娟, 等. 基于ACE Star循证模式选择新生儿经外周静脉穿刺的中心静脉导管置管部位[J]. 中南大学学报(医学版), 2020, 45(9): 1082-1088. (  0) 0) |

| [50] |

Lund CH, Osborne JW, Kuller J, et al. Neonatal skin care: clinical outcomes of the AWHONN/NANN evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Association of Women's Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses and the National Association of Neonatal Nurses[J]. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs, 2001, 30(1): 41-51. DOI:10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01520.x (  0) 0) |

| [51] |

Kieran EA, O'sullivan A, Miletin J, et al. 2% chlorhexidine-70% isopropyl alcohol versus 10% povidone-iodine for insertion site cleaning before central line insertion in preterm infants: a randomised trial[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2018, 103(2): F101-F106. DOI:10.1136/archdischild-2016-312193 (  0) 0) |

| [52] |

Aitken J, Williams FL. A systematic review of thyroid dysfunction in preterm neonates exposed to topical iodine[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2014, 99(1): F21-F28. DOI:10.1136/archdischild-2013-303799 (  0) 0) |

| [53] |

Garland JS, Alex CP, Uhing MR, et al. Pilot trial to compare tolerance of chlorhexidine gluconate to povidone-iodine antisepsis for central venous catheter placement in neonates[J]. J Perinatol, 2009, 29(12): 808-813. DOI:10.1038/jp.2009.161 (  0) 0) |

| [54] |

Chapman AK, Aucott SW, Milstone AM. Safety of chlorhexidine gluconate used for skin antisepsis in the preterm infant[J]. J Perinatol, 2012, 32(1): 4-9. DOI:10.1038/jp.2011.148 (  0) 0) |

| [55] |

Andersen C, Hart J, Vemgal P, et al. Prospective evaluation of a multi-factorial prevention strategy on the impact of nosocomial infection in very-low-birthweight infants[J]. J Hosp Infect, 2005, 61(2): 162-167. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2005.02.002 (  0) 0) |

| [56] |

Neri I, Ravaioli GM, Faldella G, et al. Chlorhexidine-Induced chemical burns in very low birth weight infants[J]. J Pediatr, 2017, 191: 262-265. DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.08.002 (  0) 0) |

| [57] |

Heron TJ, Faraday CM, Clarke P. The hidden harms of matching Michigan[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2013, 98(5): F466-F467. DOI:10.1136/archdischild-2013-304378 (  0) 0) |

| [58] |

Tamma PD, Aucott SW, Milstone AM. Chlorhexidine use in the neonatal intensive care unit: results from a national survey[J]. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2010, 31(8): 846-849. DOI:10.1086/655017 (  0) 0) |

| [59] |

Kutsch J, Ottinger D. Neonatal skin and chlorhexidine: a burning experience[J]. Neonatal Netw, 2014, 33(1): 19-23. (  0) 0) |

| [60] |

Reynolds PR, Banerjee S, Meek JH. Alcohol burns in extremely low birthweight infants: still occurring[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2005, 90(1): F10. DOI:10.1136/adc.2004.054338 (  0) 0) |

| [61] |

McCord H, Fieldhouse E, El-Naggar W. Current practices of antiseptic use in Canadian neonatal intensive care units[J]. Am J Perinatol, 2019, 36(2): 141-147. DOI:10.1055/s-0038-1661406 (  0) 0) |

| [62] |

Upadhyayula S, Kambalapalli M, Harrison CJ. Safety of anti-infective agents for skin preparation in premature infants[J]. Arch Dis Child, 2007, 92(7): 646-647. DOI:10.1136/adc.2007.117002 (  0) 0) |

| [63] |

Shime N, Hosokawa K, Maclaren G. Ultrasound imaging reduces failure rates of percutaneous central venous catheterization in children[J]. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2015, 16(8): 718-725. DOI:10.1097/PCC.0000000000000470 (  0) 0) |

| [64] |

Sabouneh R, Akiki P, Al Bizri A, et al. Ultrasound guided central line insertion in neonates: pain score results from a prospective study[J]. J Neonatal Perinatal Med, 2020, 13(1): 129-134. DOI:10.3233/NPM-180205 (  0) 0) |

| [65] |

Oleti T, Jeeva Sankar M, Thukral A, et al. Does ultrasound guidance for peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) insertion reduce the incidence of tip malposition?-a randomized trial[J]. J Perinatol, 2019, 39(1): 95-101. DOI:10.1038/s41372-018-0249-x (  0) 0) |

| [66] |

林琴, 康育兰, 林颖, 等. 床旁超声在新生儿PICC置管中的应用分析[J]. 吉林医学, 2019, 40(12): 2902-2904. (  0) 0) |

| [67] |

Sabado JJ, Pittiruti M. Principles of ultrasound-guided venous access[EB/OL].[2020-07-16]. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/principles-of-ultrasound-guided-venous-access.

(  0) 0) |

| [68] |

Katheria AC, Fleming SE, Kim JH. A randomized controlled trial of ultrasound-guided peripherally inserted central catheters compared with standard radiograph in neonates[J]. J Perinatol, 2013, 33(10): 791-794. DOI:10.1038/jp.2013.58 (  0) 0) |

| [69] |

中国医师协会新生儿科医师分会, 中国当代儿科杂志编辑委员会. 新生儿疼痛评估与镇痛管理专家共识(2020版)[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2020, 22(9): 923-930. (  0) 0) |

| [70] |

Kaur G, Gupta P, Kumar A. A randomized trial of eutectic mixture of local anesthetics during lumbar puncture in newborns[J]. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 2003, 157(11): 1065-1070. DOI:10.1001/archpedi.157.11.1065 (  0) 0) |

| [71] |

徐晓丽, 印真香, 胡莎, 等. 音乐联合母亲声音对先天性消化道畸形患儿PICC穿刺疼痛的缓解作用[J]. 中国实用护理杂志, 2019, 35(33): 2588-2593. (  0) 0) |

| [72] |

陈红敏, 陈爱民, 石彩晓, 等. 音乐疗法在早产儿PICC置管中应用的效果分析[J]. 护士进修杂志, 2018, 33(16): 1480-1482. (  0) 0) |

| [73] |

Tang L, Wang HH, Liu QH, et al. Effect of music intervention on pain responses in premature infants undergoing placement procedures of peripherally inserted central venous catheter: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Eur J Integr Med, 2018, 19: 105-109. DOI:10.1016/j.eujim.2018.03.006 (  0) 0) |

| [74] |

Bellieni CV, Tei M, Coccina F, et al. Sensorial saturation for infants' pain[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2012, 25(Suppl 1): 79-81. (  0) 0) |

| [75] |

Motz P, Von Saint Andre Von Arnim A, Iyer RS, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for peripherally inserted central catheter monitoring: a pilot study[J]. J Perinat Med, 2019, 47(9): 991-996. DOI:10.1515/jpm-2019-0198 (  0) 0) |

| [76] |

Telang N, Sharma D, Pratap OT, et al. Use of real-time ultrasound for locating tip position in neonates undergoing peripherally inserted central catheter insertion: a pilot study[J]. Indian J Med Res, 2017, 145(3): 373-376. (  0) 0) |

| [77] |

任晓玲, 陈亚娟, 刘敬, 等. 超声监测在新生儿经皮外周静脉置入中心静脉导管尖端定位中的应用[J]. 中华实用儿科临床杂志, 2019, 34(18): 1398-1401. (  0) 0) |

| [78] |

Ren XL, Li HL, Liu J, et al. Ultrasound to localize the peripherally inserted central catheter tip position in newborn infants[J]. Am J Perinatol, 2021, 38(2): 122-125. DOI:10.1055/s-0039-1694760 (  0) 0) |

| [79] |

Kadivar M, Mosayebi Z, Ghaemi O, et al. Ultrasound and radiography evaluation of the tips of peripherally inserted central catheters in neonates admitted to the NICU[J]. Iran J Pediatr, 2020, 30(6): e108416. (  0) 0) |

| [80] |

刘玲, 周星, 朱丽波, 等. 静脉内心电图引导经外周中心静脉置管导管尖端定位技术在早产儿的临床应用[J]. 中华新生儿科杂志, 2018, 33(6): 450-452. (  0) 0) |

| [81] |

王婷, 朱丽波. 腔内心电图技术定位新生儿PICC尖端位置的临床应用[J]. 临床合理用药杂志, 2018, 11(7): 169-170. (  0) 0) |

| [82] |

Ling QY, Chen H, Tang M, et al. Accuracy and safety study of intracavitary electrocardiographic guidance for peripherally inserted central catheter placement in neonates[J]. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs, 2019, 33(1): 89-95. DOI:10.1097/JPN.0000000000000389 (  0) 0) |

| [83] |

Xiao AQ, Sun J, Zhu LH, et al. Effectiveness of intracavitary electrocardiogram-guided peripherally inserted central catheter tip placement in premature infants: a multicentre pre-post intervention study[J]. Eur J Pediatr, 2020, 179(3): 439-446. DOI:10.1007/s00431-019-03524-3 (  0) 0) |

| [84] |

Racadio JM, Doellman DA, Johnson ND, et al. Pediatric peripherally inserted central catheters: complication rates related to catheter tip location[J]. Pediatrics, 2001, 107(2): E28. DOI:10.1542/peds.107.2.e28 (  0) 0) |

| [85] |

邵肖梅, 叶鸿瑁, 丘小汕. 实用新生儿学[M]. 5版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2019: 1056-1057.

(  0) 0) |

| [86] |

Albrecht K, Breitmeier D, Panning B, et al. The carina as a landmark for central venous catheter placement in small children[J]. Eur J Pediatr, 2006, 165(4): 264-266. DOI:10.1007/s00431-005-0044-5 (  0) 0) |

| [87] |

Weil BR, Ladd AP, Yoder K. Pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade associated with central venous catheters in children: an uncommon but serious and treatable condition[J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2010, 45(8): 1687-1692. DOI:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.11.006 (  0) 0) |

| [88] |

Sertic AJ, Connolly BL, Temple MJ, et al. Perforations associated with peripherally inserted central catheters in a neonatal population[J]. Pediatr Radiol, 2018, 48(1): 109-119. DOI:10.1007/s00247-017-3983-x (  0) 0) |

| [89] |

Schuster M, Nave H, Piepenbrock S, et al. The carina as a landmark in central venous catheter placement[J]. Br J Anaesth, 2000, 85(2): 192-194. DOI:10.1093/bja/85.2.192 (  0) 0) |

| [90] |

Taylor JE, Tan K, Lai NM, et al. Antibiotic lock for the prevention of catheter-related infection in neonates[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015(6): CD010336. (  0) 0) |

| [91] |

Girand HL, Mcneil JC. Lock therapy for intravascular non-hemodialysis catheter-related infection[EB/OL].[2020-07-10]. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lock-therapy-for-intravascular-non-hemodialysis-catheter-related-infection.

(  0) 0) |

| [92] |

Gillies D, O'riordan E, Carr D, et al. Central venous catheter dressings: a systematic review[J]. J Adv Nurs, 2003, 44(6): 623-632. DOI:10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02852.x (  0) 0) |

| [93] |

陈晓春, 吴益玲, 李肖肖, 等. 两种透明敷料更换频率对早产儿经外周静脉置入中心静脉导管相关性感染的影响[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2016, 26(21): 4958-4960. (  0) 0) |

| [94] |

Ullman AJ, Cooke ML, Mitchell M, et al. Dressings and securement devices for central venous catheters (CVC)[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015(9): CD010367. (  0) 0) |

| [95] |

Craven DL, BNut&Diet. Evidence Summary. Peripherally inserted central catheters (neonates): dressing of insertion site[Z]. The Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database, JBI@Ovid, 2018: JBI19643.

(  0) 0) |

| [96] |

Garland JS, Alex CP, Mueller CD, et al. A randomized trial comparing povidone-iodine to a chlorhexidine gluconate-impregnated dressing for prevention of central venous catheter infections in neonates[J]. Pediatrics, 2001, 107(6): 1431-1436. DOI:10.1542/peds.107.6.1431 (  0) 0) |

| [97] |

Milstone AM, Reich NG, Advani S, et al. Catheter dwell time and CLABSIs in neonates with PICCs: a multicenter cohort study[J]. Pediatrics, 2013, 132(6): e1609-e1615. DOI:10.1542/peds.2013-1645 (  0) 0) |

| [98] |

Crawford JD, Liem TK, Moneta GL. Management of catheter-associated upper extremity deep venous thrombosis[J]. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord, 2016, 4(3): 375-379. DOI:10.1016/j.jvsv.2015.06.003 (  0) 0) |

| [99] |

Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines[J]. Chest, 2012, 141(2 Suppl): e419S-e496S. (  0) 0) |

| [100] |

Lyman GH, Bohlke K, Khorana AA, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update 2014[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2015, 33(6): 654-656. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7351 (  0) 0) |

| [101] |

Jones MA, Lee DY, Segall JA, et al. Characterizing resolution of catheter-associated upper extremity deep venous thrombosis[J]. J Vasc Surg, 2010, 51(1): 108-113. DOI:10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.124 (  0) 0) |

| [102] |

Gnannt R, Waespe N, Temple M, et al. Increased risk of symptomatic upper-extremity venous thrombosis with multiple peripherally inserted central catheter insertions in pediatric patients[J]. Pediatr Radiol, 2018, 48(7): 1013-1020. DOI:10.1007/s00247-018-4096-x (  0) 0) |

| [103] |

Kucher N. Clinical practice. Deep-vein thrombosis of the upper extremities[J]. N Engl J Med, 2011, 364(9): 861-869. DOI:10.1056/NEJMcp1008740 (  0) 0) |

| [104] |

Shah PS, Shah VS. Continuous heparin infusion to prevent thrombosis and catheter occlusion in neonates with peripherally placed percutaneous central venous catheters[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2008(2): CD002772. (  0) 0) |

| [105] |

Bin-Nun A, Wasserteil N, Nakhash R, et al. Heparinization of long indwelling lines in neonates: systematic review and practical recommendations[J]. Isr Med Assoc J, 2016, 18(11): 692-696. (  0) 0) |

| [106] |

彭易, 程云, 芦婳, 等. 肝素稀释液维持新生儿PICC导管通畅作用的meta分析[J]. 中华护理杂志, 2012, 47(11): 1023-1027. (  0) 0) |

| [107] |

Uslu S, Ozdemir H, Comert S, et al. The effect of low-dose heparin on maintaining peripherally inserted percutaneous central venous catheters in neonates[J]. J Perinatol, 2010, 30(12): 794-799. DOI:10.1038/jp.2010.46 (  0) 0) |

| [108] |

Shah PS, Kalyn A, Satodia P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of heparin versus placebo infusion to prolong the usability of peripherally placed percutaneous central venous catheters (PCVCs) in neonates: the HIP (Heparin Infusion for PCVC) study[J]. Pediatrics, 2007, 119(1): e284-e291. DOI:10.1542/peds.2006-0529 (  0) 0) |

| [109] |

Birch P, Ogden S, Hewson M. A randomised, controlled trial of heparin in total parenteral nutrition to prevent sepsis associated with neonatal long lines: the Heparin in Long Line Total Parenteral Nutrition (HILLTOP) trial[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2010, 95(4): F252-F257. DOI:10.1136/adc.2009.167403 (  0) 0) |

| [110] |

Kamala F, Boo NY, Cheah FC, et al. Randomized controlled trial of heparin for prevention of blockage of peripherally inserted central catheters in neonates[J]. Acta Paediatr, 2002, 91(12): 1350-1356. (  0) 0) |

| [111] |

唐军, 熊英. 肝素预防新生儿经外周中心静脉置管相关感染的回顾性研究[J]. 中国循证医学杂志, 2010, 10(9): 1023-1026. (  0) 0) |

| [112] |

Barekatain B, Armanian AM, Salamaty L, et al. Evaluating the effect of high dose versus low dose heparin in peripherally inserted central catheter in very low birth weight infants[J]. Iran J Pediatr, 2018, 28(3): e60800. (  0) 0) |

| [113] |

Ista E, van der Hoven B, Kornelisse RF, et al. Effectiveness of insertion and maintenance bundles to prevent central-line-associated bloodstream infections in critically ill patients of all ages: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2016, 16(6): 724-734. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00409-0 (  0) 0) |

| [114] |

Payne V, Hall M, Prieto J, et al. Care bundles to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections in the neonatal unit: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2018, 103(5): F422-F429. DOI:10.1136/archdischild-2017-313362 (  0) 0) |

| [115] |

Romantsik O, Bruschettini M, Zappettini S, et al. Heparin for the treatment of thrombosis in neonates[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016(11): CD012185. (  0) 0) |

| [116] |

Chow LM, Friedman JN, Macarthur C, et al. Peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) fracture and embolization in the pediatric population[J]. J Pediatr, 2003, 142(2): 141-144. DOI:10.1067/mpd.2003.67 (  0) 0) |

| [117] |

Miall LS, Das A, Brownlee KG, et al. Peripherally inserted central catheters in children with cystic fibrosis. Eight cases of difficult removal[J]. J Infus Nurs, 2001, 24(5): 297-300. DOI:10.1097/00129804-200109000-00003 (  0) 0) |

| [118] |

Sharpe EL, Roig JC. A novel technique for difficult removal of a neonatal peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC)[J]. J Perinatol, 2012, 32(1): 70-71. DOI:10.1038/jp.2011.57 (  0) 0) |

2021, Vol. 23

2021, Vol. 23