婴幼儿喘息与支气管哮喘(bronchial asthma,以下简称哮喘)密切相关,高达40%的喘息婴幼儿日后可发展为哮喘[1]。喘息婴幼儿生命早期已存在气道炎症,甚至已发生气道重塑[2-3],不管喘息患儿是否具备特应性体质,都存在类似哮喘的气道病理改变,但其具体发生机制尚未清楚[4-5]。那么,婴幼儿喘息是否与哮喘存在相似的发病机制?Th1/Th2失衡是哮喘免疫学发病机制中的一个重要环节[6-8],细胞因子网络失衡在哮喘发病中起着重要作用:主要表现为以白介素(interleukin, IL)-2为代表的Th1细胞因子低表达;而Th2型细胞因子如IL-4、IL-5、IL-13及转化生长因子-β1(transforming growth factor-β1, TGF-β1)高表达。IL-2、IL-4、IL-5、IL-13、TGF-β1及IgE作为哮喘发病过程中重要的因子,通过错综复杂的机制及相互作用参与了哮喘免疫学发病机制、气道炎症及气道重塑的发生发展[9-15]。Abrahamsson等[16]研究表明出生时具有高水平Th2相关趋化因子受体的儿童更易发展为反复喘息。国内郁志伟等[17]发现婴幼儿喘息性肺炎存在γ干扰素/IL-4比值失衡,存在气道嗜酸性粒细胞炎症,但Pitrez等[18]研究认为喘息婴儿与Th1/Th2相关细胞因子的表达水平无明显相关性。Th1/Th2失衡是否参与婴幼儿喘息发生发展,目前仍具有争议。本研究通过回顾性分析喘息婴幼儿外周血IL-2、IL-4、IL-5、IL-13、TGF-β1及总IgE(TIgE)水平,比较它们在不同喘息次数、不同哮喘高危因素、不同病原学的喘息婴幼儿中的差异,从Th1/Th2失衡及气道炎症两个方面来探讨婴幼儿喘息性疾病可能的发生机制。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象及分组选取2014年6月至2015年3月期间在中南大学湘雅医院儿科就诊的喘息婴幼儿50例为喘息组。诊断标准符合《诸福棠实用儿科学》第7版[19]。纳入标准:(1)足月出生,年龄1个月至3岁;(2)伴有咳嗽、喘息、呼气时间延长;(3)肺部可闻及哮鸣音。排除标准:(1)入院前两周内使用激素和白三烯调节剂类药物;(2)心源性哮喘、肺结核、百日咳、支气管异物、支气管肺发育不良、大气道梗阻等其他原因所致的喘息。

50例喘息患儿进行如下分组:(1)根据既往喘息发作次数,分为首次喘息组(首发组)和反复喘息组(反复组,发作次数≥2次),其中首发组25例,包括男19例,女6例,平均年龄9.9±9.1个月;反复组25例,包括男20例,女5例,平均年龄14.9±9.9个月。(2)根据是否存在哮喘发生的高危因素[4],分为有高危因素组和无高危因素组;高危因素包括:父母哮喘病史,经医生诊断的特应性皮炎,有吸入变应原或食物变应原致敏的依据,外周血嗜酸性粒细胞百分比(EOS%)≥4%,与感冒无关的喘息;有上述高危因素之一者纳入有高危因素组,共22例,其中男16例,女6例,平均年龄12.3±8.9个月,包括有湿疹史者11例,对牛奶过敏者2例,家族中有哮喘病史者1例,外周血EOS%≥4%者7例,同时有湿疹及哮喘家族史者1例;无高危因素组28例,其中男23例,女5例,平均年龄12.2±10.7个月。(3)根据病原学检测结果,将1种或多种病原学监测阳性者纳入病原学阳性组,所有病原学检测均为阴性者纳入病原学阴性组。病原学阳性组23例,其中男17例,女6例,平均年龄11.5±8.8个月;病原学阴性组27例,其中男22例,女5例,平均年龄13.2±10.7个月。另选取于本院门诊行健康体检的正常婴幼儿25例作为健康对照组。健康对照组婴幼儿无喘息及慢性咳嗽病史,体检心肺无异常,4周内无呼吸道感染病史,否认个人及家族过敏史。各组年龄、性别比较差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。本研究已获得我院医学伦理委员会的批准和家长知情同意。

1.2 实验室指标测定采集所有喘息患儿及健康对照组婴幼儿静脉血2 mL,分离血清并储存于-70℃冰箱待测。ELISA法检测TIgE、TGF-β1水平,检测试剂盒由美国R & D公司提供;液相悬浮芯片技术检测IL-2、IL-4、IL-5、IL-13水平,试剂由美国R & D公司提供。喘息患儿同时送检外周血嗜酸性粒细胞(EOS)计数,使用间接免疫荧光法测定嗜肺军团菌血清1型(LP)IgM抗体、肺炎支原体(MP)IgM抗体、Q热立克次体(CB)IgM抗体、肺炎衣原体(CP)IgM抗体、腺病毒(ADV)IgM抗体、呼吸道合胞病毒(RSV)IgM抗体、甲型流感病毒(Influenza A virus)IgM抗体、乙型流感病毒(Influenza B virus)IgM抗体、副流感病毒(HPIVs)IgM抗体(试剂由西班牙VIRCELL公司提供),进行痰培养、咽拭子肺炎支原体(MP)培养(试剂由陕西百盛园生物科技信息有限公司生产提供)。以上检测均由湘雅医院检验科及儿科实验室完成。

1.3 统计学分析采用SPSS 19.0统计软件对数据进行统计学分析。不符合正态分布计量资料用中位数(范围)表示,两组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验,多组间比较采用Kruskal-Wallis H检验,组间两两比较采用Bonferroni法;对各实验室指标之间进行Spearman等级相关分析。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 喘息组与健康对照组外周血细胞因子及TIgE水平喘息组婴幼儿外周血IL-2水平与健康对照组相比差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05);喘息组婴幼儿外周血IL-4、IL-5、IL-13、TGF-β1及TIgE水平均较健康对照组明显升高(P < 0.05)。见表 1。

| 表 1 喘息组与健康对照组外周血细胞因子及TIgE水平比较 [中位数(范围)] |

|

|

首发组、反复组婴幼儿外周血IL-4、IL-5、IL-13及TGF-β1水平均较健康对照组明显升高(P < 0.05)。首发组外周血IL-2、IL-4、IL-5、IL-13、TGF-β1及TIgE水平与反复组相比,差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。见表 2。

| 表 2 健康对照组、首发组和反复组外周血细胞因子及TIgE水平比较 [中位数(范围)] |

|

|

三组间外周血IL-2水平比较,差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05);有哮喘高危因素组及无哮喘高危因素组外周血IL-4、IL-5、IL-13、TGF-β1及TIgE水平均高于健康对照组(P < 0.05);有哮喘高危因素组和无哮喘高危因素组外周血IL-4、IL-5、IL-13、TGF-β1及TIgE水平比较,差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。见表 3。

| 表 3 健康对照组、无高危因素组和有高危因素组外周血细胞因子及TIgE水平比较 [中位数(范围)] |

|

|

三组间外周血IL-2水平比较,差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05);病原学阳性组及病原学阴性组外周血IL-4、IL-5、IL-13、TGF-β1及TIgE水平均高于健康对照组(P < 0.05);病原学阳性组和病原学阴性组外周血IL-4、IL-5、IL-13、TGF-β1及TIgE水平比较,差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。见表 4。

| 表 4 健康对照组、病原学阴性组和病原学阳性组外周血细胞因子及TIgE水平比较 [中位数(范围)] |

|

|

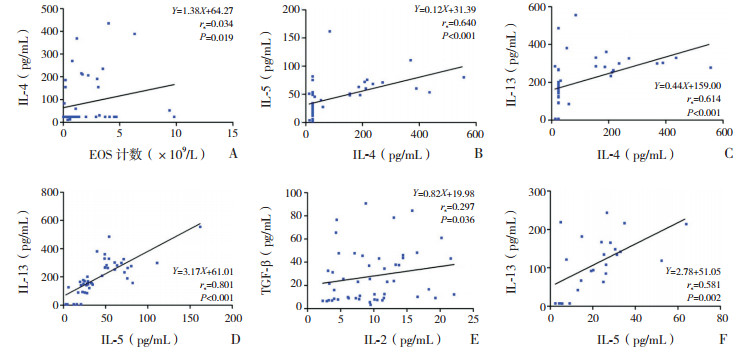

相关性分析结果显示:喘息组外周血EOS计数与IL-4水平呈正相关(rs=0.034,P < 0.05);IL-4水平分别与IL-5、IL-13水平呈正相关(分别为rs=0.640,P < 0.01;rs=0.614,P < 0.01);IL-5水平与IL-13水平呈正相关(rs=0.801,P < 0.01);IL-2水平与TGF-β1水平呈正相关(rs=0.297,P < 0.05)。健康对照组IL-5水平与IL-13水平呈正相关(rs=0.581,P < 0.01)。见图 1。

|

图 1 外周血EOS计数、细胞因子及TIgE水平间的相关性分析 A~E为喘息组,F为健康对照组。 |

喘息是困扰婴幼儿最常见的呼吸道症状之一,婴幼儿喘息性疾病是一种异质性疾病,与支气管肺发育的成熟、早产、烟草暴露、母亲患哮喘、呼吸道病毒感染、特应性体质等高危因素有关[20-23]。与其他年龄组相比,学龄前儿童喘息(年龄≤5岁)有较高的哮喘发病率[24-26],据统计,学龄前喘息儿童于急诊科就诊的年增长率在23‰~42‰,占用了大量医疗资源,也给儿科临床医生带来了诊断方面的挑战。在发展中国家,学龄前儿童喘息常被误诊为肺炎进行治疗,导致这个年龄组患儿病死率增加,这些被诊断为复发性肺炎的患儿往往在后来被诊断为哮喘[27-28]。

IL-2为代表性的Th1细胞因子,能促进所有亚型T细胞的增殖及产生细胞因子,增强NK细胞毒性。IL-4参与哮喘主要通过诱导Th2细胞的分化、促进B细胞合成IgE、EOS聚集、肥大细胞生长及黏液化生,同时IL-4通过上调胶原蛋白及纤维蛋白参与气道重塑[29],IL-5与EOS的活化、气道炎症、气道高反应性(airway hyperresponsiveness, AHR)及IgE的合成密切相关。IL-13在哮喘炎症过程中起主导作用,它可以单独介导并引起哮喘[30],与气道的炎症反应和免疫调节有关。TGF-β1具有强大的促炎及抗炎作用,被认为是哮喘气道炎症和气道重塑中最重要的炎性介质。IgE参与了哮喘气道炎症及AHR[31],故血清TIgE水平也被认为是AHR的指标。

本研究结果显示,虽然外周血IL-2水平在喘息组与健康对照组间变化不明显,但喘息组Th2细胞因子IL-4、IL-5、IL-13水平较健康对照组明显升高,表明IL-4、IL-5、IL-13参与了婴幼儿喘息性疾病的发病过程,喘息婴幼儿存在气道炎症,提示喘息组婴幼儿存在Th1/Th2失衡,即Th2的优势表达,与国内外某些学者报道均一致[15-17]。喘息婴幼儿Th2应答相对亢进,IL-4、IL-5及IL-13产生过多所促发的气道炎症及AHR可能是造成喘息发生的重要原因,这与哮喘发病的免疫学机制相似。

TGF-β1是目前发现的最强的促纤维化因子,被认为是哮喘气道炎症和气道重塑中最重要的炎性介质[32-33],TGF-β1的表达强弱被认为与哮喘发作严重程度密切相关[34],喘息组TGF-β1水平的升高,提示喘息患儿不仅存在气道炎症,而且可能存在气道重塑的高危因素。本研究结果显示喘息组患儿外周血TIgE水平明显高于健康对照组,提示IgE参与了婴幼儿喘息性疾病的发病过程[35-37]。

对于学龄前儿童,反复喘息次数为哮喘预测指数的重要因素,因此本研究中将急性喘息发作的婴幼儿进一步分为了首发组及反复组(发作次数≥2次),比较两组间外周血IL-4、IL-5、IL-13及TGF-β1差异,以了解反复喘息对气道炎症介质的影响。结果发现首发组及反复组患儿外周血IL-4、IL-5、IL-13及TGF-β1水平均高于健康对照组,但首发组与反复组患儿外周血IL-2、IL-4、IL-5、IL-13、TGF-β1及TIgE水平无差异,原因可能是:(1)既往有过多次喘息发作的患儿中存在接受过短期吸入性糖皮质激素及白三烯受体拮抗剂孟鲁司特治疗者,治疗可能抑制了这部分患儿气道炎症的发生发展;(2)两组患儿均处于喘息急性发作期,为疾病的高峰期,体内细胞因子及炎症因子水平可能较喘息缓解期急剧升高。

为了解哮喘高危因素对喘息婴幼儿的影响,将喘息组患儿进一步分为有哮喘高危因素组和无哮喘高危因素组,结果显示有哮喘高危因素组及无哮喘高危因素组患儿外周血IL-4、IL-5、IL-13及TGF-β1水平均高于健康对照组,说明两组患儿均存在气道炎症;但两组外周血IL-2、IL-4、IL-5,IL-13、TGF-β1及TIgE水平无差异,提示喘息婴幼儿的气道炎症与是否存在哮喘高危因素无关。

呼吸道感染是导致或加重婴幼儿喘息的原因[37],本研究结果表明,病原学检测阳性者占喘息组患儿的46%,提示感染可能是诱发及加重喘息的原因。结果显示病原学阳性组及病原学阴性组外周血IL-4、IL-5、IL-13、TGF-β1及TIgE均高于健康对照组,表明两组患儿体内存在多种细胞因子紊乱,均存在气道炎症,但病原学阳性组和病原学阴性组外周血IL-2、IL-4、IL-5、IL-13、TGF-β1及TIgE水平比较,差异无统计学意义,提示不论病原学检测阳性还是阴性的喘息婴幼儿都存在气道炎症,都应加强随访,规范治疗。

相关性分析显示,喘息组患儿外周血EOS计数与IL-4水平呈显著正相关。喘息组患儿IL-4水平与IL-5、IL-13水平呈显著正相关;IL-5水平与IL-13水平呈显著正相关,原因可能是三者在结构及功能上存在密切联系,三者在喘息急性发作期同时增高,提示三者可能共同参与了喘息急性发作,且三者之间可能具有促进作用,从而加重喘息的发生与发展,此外,三者同为Th2型细胞因子,也进一步支持喘息婴幼儿存在Th2优势表达。喘息组患儿IL-2水平与TGF-β1水平呈显著正相关,考虑IL-2系Th1型细胞因子,对免疫应答有负性调控作用,而TGF-β1也是具有强大抗炎及促炎作用的因子,二者在抑制炎症反应上的作用机制有相互联系。健康对照组IL-5水平与IL-13水平呈显著正相关,考虑IL-5及IL-13均为Th2细胞分泌,两者间可能具有促进作用。

综上所述,本研究结果表明喘息组婴幼儿存在Th1/Th2失衡,表现为Th2优势表达。IL-4、IL-5,IL-13、TGF-β1及IgE参与了婴幼儿喘息性疾病的发病过程,无论是首次还是反复多次喘息发作的婴幼儿,在急性发作期都存在气道炎症,与是否存在哮喘高危因素及病原学检测是否阳性无关。

| [1] |

Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, et al. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life[J]. N Engl J Med, 1995, 332(3): 133-138. DOI:10.1056/NEJM199501193320301 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Fehrenbach H, Wagner C, Wegmann M. Airway remodeling in asthma:what really matters[J]. Cell Tissue Res, 2017, 367(3): 551-569. DOI:10.1007/s00441-016-2566-8 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Lezmi G, Gosset P, Deschildre A, et al. Airway remodeling in preschool children with severe recurrent wheeze[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2015, 192(2): 164-171. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201411-1958OC (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Turato G, Barbato A, Baraldo S, et al. Nonatopic children with multitrigger wheezing have airway pathology comparable to atopic asthma[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2008, 178(5): 476-482. DOI:10.1164/rccm.200712-1818OC (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Martin Alonso A, Saglani S. Mechanisms mediating pediatric severe asthma and potential novel therapies[J]. Front Pediatr, 2017, 5: 154. DOI:10.3389/fped.2017.00154 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Bertelsen RJ, Rava M, Carsin AE, et al. Clinical markers of asthma and IgE assessed in parents before conception predict asthma and hayfever in the offspring[J]. Clin Exp Allergy, 2017, 47(5): 627-638. DOI:10.1111/cea.12906 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Lockett GA, Soto-Ramírez N, Ray MA, et al. Association of season of birth with DNA methylation and allergic disease[J]. Allergy, 2016, 71(9): 1314-1324. DOI:10.1111/all.12882 (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Chawes BL. Low-grade disease activity in early life precedes childhood asthma and allergy[J]. Dan Med J, 2016, 63(8): pii:B5272. (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Wang RS, Jin HX, Shang SQ, et al. Associations of IL-2 and IL-4 expression and polymorphisms with the risks of mycoplasma pneumoniae infection and asthma in children[J]. Arch Bronconeumol, 2015, 51(11): 571-578. DOI:10.1016/j.arbres.2014.11.004 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Xia Y, Cai PC, Yu F, et al. IL-4-induced caveolin-1-containing lipid rafts aggregation contributes to MUC5AC synthesis in bronchial epithelial cells[J]. Respir Res, 2017, 18(1): 174. DOI:10.1186/s12931-017-0657-z (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Medrek SK, Parulekar AD, Hanania NA. Predictive biomarkers for asthma therapy[J]. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep, 2017, 17(10): 69. DOI:10.1007/s11882-017-0739-5 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Singhania A, Wallington JC, Smith CG, et al. Multitissue transcriptomics delineates the diversity of airway T cell functions in asthma[J]. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 2018, 58(2): 261-270. DOI:10.1165/rcmb.2017-0162OC (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Costa RD, Figueiredo CA, Barreto ML, et al. Effect of polymorphisms on TGFB1 on allergic asthma and helminth infection in an African admixed population[J]. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol, 2017, 118(4): 483-488. DOI:10.1016/j.anai.2017.01.028 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Gon Y, Ito R, Maruoka S, et al. Long-term course of serum total and free IgE levels in severe asthma patients treated with omalizumab[J]. Allergol Int, 2018, 67(2): 283-285. DOI:10.1016/j.alit.2017.08.003 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Chkhaidze I, Zirakishvili D, Shavshvishvili N, et al. Prognostic value of TH1/TH2 cytokines in infants with wheezing in a three year follow-up study[J]. Pneumonol Alergol Pol, 2016, 84(3): 144-150. DOI:10.5603/PiAP.2016.0016 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Abrahamsson TR, Sandberg Abelius M, Forsberg A, et al. A Th1/Th2-associated chemokine imbalance during infancy in children developing eczema, wheeze and sensitization[J]. Clin Exp Allergy, 2011, 41(12): 1729-1739. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03827.x (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

郁志伟, 钱俊, 顾晓虹, 等. 婴幼儿喘息性社区获得性肺炎患儿血清炎症因子的变化[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2015, 17(8): 815-818. (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Pitrez PM, Machado DC, Jones MH, et al. Th-1 and Th-2 cytokine production in infants with virus-associated wheezing[J]. Braz J Med Biol Res, 2005, 38(1): 51-54. DOI:10.1590/S0100-879X2005000100008 (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

胡亚美, 江载芳. 诸福棠实用儿科学[M]. 第7版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2002: 1171-1204.

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Ducharme FM, Tse SM, Chauhan B. Diagnosis, management, and prognosis of preschool wheeze[J]. Lancet, 2014, 383(9928): 1593-1604. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60615-2 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Ng MC, How CH. Recurrent wheeze and cough in young children:is it asthma?[J]. Singapore Med J, 2014, 55(5): 236-241. DOI:10.11622/smedj.2014064 (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Grad R, Morgan WJ. Long-term outcomes of early-onset wheeze and asthma[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2012, 130(2): 299-307. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.022 (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Beigelman A, Chipps BE, Bacharier LB. Update on the utility of corticosteroids in acute pediatric respiratory disorders[J]. Allergy Asthma Proc, 2015, 36(5): 332-338. DOI:10.2500/aap.2015.36.3865 (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Belhassen M, De Blic J, Laforest L, et al. Recurrent wheezing in infants:apopulation-based study[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2016, 95(15): e3404. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000003404 (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Ozdogan S, Tabakci B, Demirel AS, et al. The evaluation of risk factors for recurrent hospitalizations resulting from wheezing attacks in preschool children[J]. Ital J Pediatr, 2015, 41: 91. DOI:10.1186/s13052-015-0201-z (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Østergaard MS, Nantanda R, Tumwine JK, et al. Childhood asthma in low income countries:an invisible killer?[J]. Prim Care Respir, 2012, 21(2): 214-219. DOI:10.4104/pcrj.2012.00038 (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Wen T, Besse JA, Mingler MK, et al. Eosinophil adoptive transfer system to directly evaluate pulmonary eosinophil trafficking in vivo[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013, 110(15): 6067-6072. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1220572110 (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Fulkerson PC, Rothenberg ME. Targeting eosinophils in allergy, inflammation and beyond[J]. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2013, 12(2): 117-129. (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

D'Agostino B, Gallelli L, Falciani M, et al. Endothelin-1 induced bronchial hyperresponsiveness in the rabbit:an ET(A) receptor-mediated phenomenon[J]. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol, 1999, 360(6): 665-669. DOI:10.1007/s002109900146 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Van der Pouw Kraan TC, Van der Zee JS, Boeije LC, et al. The role of IL-13 in IgE synthesis by allergic asthma patients[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 1998, 111(1): 129-135. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00471.x (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Hamelmann E, Tadeda K, Oshiba A, et al. Role of IgE in the development of allergic airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness -a murine model[J]. Allergy, 1999, 54(4): 297-305. DOI:10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00085.x (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Ierodiakonou D, Postma DS, Koppelman GH, et al. TGF-β1 polymorphisms and asthma severity, airway inflammation, and remodeling[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2013, 131(2): 582-585. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.08.013 (  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Das S, Miller M, Beppu AK, et al. GSDMB induces an asthma phenotype characterized by increased airway responsiveness and remodeling without lung inflammation[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2016, 113(46): 13132-13137. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1610433113 (  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Ma Y, Huang W, Liu C, et al. Immunization against TGF-β1 reduces collagen deposition but increases sustained inflammation in a murine asthma model[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2016, 12(7): 1876-1885. (  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Szefler SJ, Wenzel S, Brown R, et al. Asthma outcomes:biomarkers[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2012, 129(3 Suppl): S9-S23. (  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Tu YL, Chang SW, Tsai HJ, et al. Total serum IgE in a population-based study of Asian children in Taiwan:reference value and significance in the diagnosis of allergy[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(11): e80996. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0080996 (  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Eggo RM, Scott JG, Galvani AP, et al. Respiratory virus transmission dynamics determine timing of asthma exacerbation peaks:evidence from a population-level model[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016, 113(8): 2194-2199. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1518677113 (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 21

2019, Vol. 21